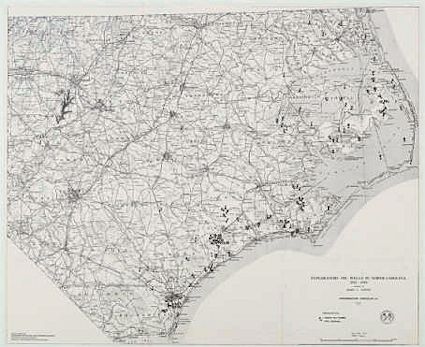

The dots mark the locations of exploratory oil wells that were drilled in North Carolina from 1925 to 1976. Photo: N.C. Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill |

BUXTON — Maybe those wildcatters who drilled for oil on Hatteras Island 70 years ago found black gold after all. Except now no one on the Outer Banks is counting on any big fortune coming their way.

After a recent re-examination of bore cuttings from a well dug in 1965 off Hyde County, called Mobil No. 3, revealed evidence of oil, state geologists have decided to take another look at samples from the old Buxton well that is directly due east.

Supporter Spotlight

The initial finding is significant: It is the first time oil has been detected from offshore North Carolina, rather than inferred from seismic testing. “We actually have something in an actual rock,” said Kenneth B. Taylor, state geologist with the N.C. Geological Survey.

Back in 1945, when ESSO No. 1 – the oil well that Standard Oil called “the most important wildcat venture in eastern America in 1945 and 1946” – was drilled deep into the sand near the current location of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the economy on the Outer Banks was hurting, jobs were scarce and the sudden appearance of the oil company was welcomed.

“The talk, I guess, was of hope,” recalled Tommy Gray Sr., a 95-year-old Avon native. “They were hoping they’d strike oil.”

Gray remembers that two of his cousins worked with Standard Oil of New Jersey on the project, but it ended up a bust and after a couple of years the well was plugged.

“They weren’t there that long,” he said.

Supporter Spotlight

Moon Tillett, a Wanchese waterman and founder of Moon Tillett Fish House, says he was about 16 years old when he worked with his father Billy Tillett running a survey boat for the oil company.

Moon Tillett of Wanchese helped his father run the survey boats for the oil companies. Photo: Outer Banks Voice |

Tillett, who will be 85 next month, said he remembers dynamite being used at the Buxton site. He also helped at other sites they drilled, including one in Pamlico Sound off Oregon Inlet. “We jumped from one boat to another,” he recalled.

They were each paid about $150 a month, Tillett said, and the boats earned about $700 , which was good money then. “You know, it came at a time when there wasn’t much going on here,” he says. “It gave a lot of people work. It was a big help to Dare County.”

But Sybil Ross, a 67-year-old Manteo native, said there would be no Cape Hatteras National Seashore, established in 1953, if those leases on Hatteras Island had remained active.

“There was a lot of controversy and the oil companies almost won back then,” she said. “But they didn’t – we got the park.”

Other oil companies showed up on the Outer Banks about 20 to 30 years later to drill at various locales, including Stumpy Point, East Lake, Mashoes, Manteo and Manns Harbor.

Thinking back, Roger Best, 80, said that it was “kind of hilarious” that his Stumpy Point neighbors were convinced that their fortune was upon them. “They all thought they were going to get rich,” Best says with a chuckle. “It was really a time.”

Best, a retired fisherman and boat painter, said that land was leased in the community by the oil company – the name is long forgotten — and equipment was brought in. For awhile, everyone was seeing dollar signs. But nothing ever came of it. “They were really going to it,” he said of the venture. “They even hired a secretary here.”

Ken Taylor |

The first exploratory oil well in North Carolina was dug near Havelock in 1925. By the time the last one was drilled in Lee County in 1998, a total of 120 wells had been dug in 23 counties, mostly on the coast. The deepest one was Esso No. 1 at Cape Hatteras, with a depth of 10,044 feet. Until now, all were officially deemed dry.

Taylor said that back then, unless a well had producible oil, no one could be bothered with it. The well would be capped and forgotten. And in the early years, if they tapped natural gas, it would just be burned off as a useless product.

Charles Meekins, 81, also from Stumpy Point, said that he remembers that a public relations man from an oil company came to the talk to community three or four times and got everyone worked up.

“He told everybody they were going to be millionaires,” Meekins said. “He was very good – kind of like a car salesman. He just had a convincing personality and people believed it.”

Everyone was offered $1 to lease their land, Meekins recalled, with the promise they would make “this multitude of money” on the vast amount of oil they were led to believe was under their sandy yards.

Meekins said that a single well was drilled at the site of the old Navy barracks owned by resident Laverne Twiford – where according to the salesman, oil was practically ready to gush forth. For a while, there were a lot of heavy pipes and a derrick near the property, long after the wildcatters left town. As far as Meekins knows, he said, all anyone in Stumpy Point ever got out of the deal was the $1 fee.

“Laverne died in poverty,” he said, “just like of rest of us fishermen.”

Since that failed adventure in Stumpy Point and other Dare County sites, only areas offshore Cape Hatteras have held any interest to oil companies. Serious pursuits in the late 1980s by Mobil Oil Corp and in the late ‘90s by Chevron USA were made to explore lease units off Hatteras, where there are purportedly deposits of natural gas. Both proposals were eventually dropped under vigorous public opposition over concerns about environmental damage and destruction of the huge tourism industry.

But now North Carolina, with the blessing of the federal government, is interested in exploring oil and gas production, including offshore resources. In the process, the state is updating its inventory of potential hydrocarbon deposits.

People frolic along the Playa del Rey beach in California in the mid-20th century. The skyline is dominated by oil derricks. This could have been what the Outer Banks would have looked like if oil was found. The residents there thought they, too, would cash in on the oil bonanza. Photo: California Historical Society Collection, USC Libraries. |

That’s what led to a re-examination of the well cuttings that have been sitting for decades in boxes.

The first well the state looked at was Mobil No. 3, the ninth well drilled in Hyde County, said Taylor, the state geologist. Using modern spectrometry technology, the core cuttings revealed indications of hydrocarbons, he explained, but the rocks they examined were not “thermally mature” enough to generate the biogenic and thermogenic components of the oil. So the question was, where did the oil come from?

The answer, Taylor said, could be found in cuttings from Esso No. 1, which is just east of Mobil No. 3. The indicators of petroleum and natural gas in the Mobil well were found at a deep level of earth that would allow the oil to drift from the Esso well. If that’s the case, the Esso well could be sitting in a vein of hydrocarbons.

“There might be something offshore,” Taylor said.

An August article about the analysis in Search and Discovery, and online journal for geoscientists, said that the results of the initial examination of the cuttings show evidence of oil and gas.

“Further geochemical research is needed to understand more completely how these elements may integrate fully into an understanding of a total petroleum system for the North Carolina continental shelf and slope,” the report said.

Taylor said that the state plans to examine the old data with new technology to see if the initial analysis can be confirmed. If it is, the findings will be peer reviewed and then published for the public. The entire process could take about two years.

“These samples were sitting in these little boxes , waiting for the science to catch up,” he said. “We couldn’t have done this in 1965.”