Principal N.C. Coastal AquifersLower Cape Fear aquifer: This aquifer is present in the northwestern portion of the coastal plain at elevations of -9 to -3,260 feet, averaging -798 feet (referenced to mean sea level). The Lower Cape Fear aquifer ranges from 1 to 3,081 feet thick and averages 394 feet thick. The aquifer is composed of fine to coarse sands. Wells typically yield 200-400 gallons a minute. Upper Cape Fear aquifer: This aquifer is present in the western portions of the coastal plain at elevations of 295 to -2,394 feet, averaging -387 feet. The Upper Cape Fear aquifer ranges from 3 to 3,892 feet thick and averages 185 feet thick. The aquifer is composed of very fine to coarse sands and occasional gravels. Wells typically yield 200-400 gallons a minute. Supporter SpotlightBlack Creek aquifer: This aquifer is present in the central and southwestern portions of the coastal plain at elevations of 318 to -1,477 feet, averaging -172 feet. The Black Creek aquifer ranges from 14 to 448 feet thick and averages 160 feet thick. The aquifer is composed of very fine to fine “salt and pepper” sands. Wells typically yield 200-400 gallons a minute. Peedee aquifer: This aquifer is present in the central to southeastern portion of the coastal plain at elevations of 114 to -1,842 feet, averaging -164 feet. The Peedee aquifer ranges from 2 to 1,001 feet thick and averages 142 feet thick. The aquifer is composed of fine to medium sand. Wells typically yield up to 200 gallons a minute. Castle Hayne aquifer: This aquifer is widely used in the eastern portions of the coastal plain at elevations of 65 to -1,091 feet, averaging -143 feet. The Castle Hayne aquifer ranges from 6 to 1,105 feet thick and averages 165 feet thick. The aquifer is composed of limestone, sandy limestone, and sand. It is the most productive aquifer in North Carolina. Wells typically yield 200-500 gallons a minute, but can exceed 2,000 gallons a minute. Yorktown aquifer: This aquifer is present throughout most of the northern coastal plain at elevations ranging from 97 to -222 feet, averaging -17 feet. The Yorktown aquifer ranges from 4 to 992 feet thick and averages 133 feet thick. Several localities tap this aquifer and produce high yielding wells including Roanoke Island, Kill Devil Hills and Elizabeth City. Yorktown aquifer is composed of fine sand, silty and clayey sand, shell beds and coarser sand beds. Wells typically yield 15-90 gallons a minute. Surficial aquiferThis aquifer is widely used throughout the state for individual home wells. The surficial aquifer is the shallowest and most susceptible to contamination from septic tank systems and other pollution sources. The surficial aquifer is also very sensitive to variations in rainfall amounts — they are the first to dry-up in a drought. On the Outer Banks shallow wells are subject to rainfall amounts, saltwater intrusion, poor quality ground water and ocean overwash. Wells typically yield 25-200 gallons a minute. Supporter Spotlight— N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources |

WILMINGTON – Saltwater has migrated inland into freshwater aquifers that supply hundreds of private and public wells in the New Hanover County area, according to a new U.S. Geological Survey report.

Water levels in some areas of the aquifers from which residents, businesses and industries in the county draw their drinking water have also dropped several feet below sea level, according to the recently released study initiated by the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority.

The results of the study are a telltale sign of how the demand from a population that has exploded since the 1990s has affected aquifers, sources that will continue to be pressured if population growth projections are fulfilled and new industries move to the area.

Gary McSmith, engineering manager with the planning and design division of the utility, is confident the utility will be able to meet future water demands, including new customers whose private wells succumb to saltwater infiltration.

That doesn’t preclude the fact that saltwater infiltration is an irreversible process or that it takes centuries for aquifers to naturally recharge.

“I think probably the most important part of this study is that there has been a dramatic change from 1964 until now,” said Kristen McSwain, a hydrologist with the Geologic Survey’s South Atlantic Water Science Center and co-author of the report. “Because New Hanover County is growing the withdrawals from groundwater for public supply and for homeowners’ wells are increasing each year.”

Gary McSmith |

Researchers sampled 97 wells in New Hanover, southern Pender and eastern Brunswick counties between late August and early September 2012 and again in March 2013.

Samples collected in 2012 were gathered intentionally at summer’s end when water use is high because of irrigation and the tourism season. Researchers examined those samples for water levels and water quality of the Peedee and Castle Hayne aquifers. Samples taken in March, generally a period when aquifers recharge, examined water levels only.

“In terms of major ion chemistry what we found is that seawater is mixing with groundwater in both the Castle Hayne and Peedee aquifers in a couple of locations in Brunswick, New Hanover and Pender counties,” McSwain said. “These concentrations have moved inland since 1965 with the area showing the greatest increase in northeastern New Hanover County in between Futch and Pages Creek. The saltwater/freshwater interface is usually sitting off the coast. Because of pressure changes in the aquifer we have withdrawn groundwater at a rate faster than it is recharging.”

The lowest groundwater altitude in the Castle Hayne aquifer measured at about 6.5 feet below sea level when measured in 2012 and by March the lowest level was roughly eight feet below sea level, she said. In the Peedee aquifer the lowest groundwater altitude measured at around 20 feet below sea level in 2012 andin March 2013 at about 15 feet below sea level.

Compared to the last geological survey of these groundwater resources in 1964, the Castle Hayne aquifer has rebounded by about 10 feet in the downtown Wilmington area, but it has dropped more than 20 feet near Pages Creek, McSwain said.

Water level declines of 10 feet were calculated over large areas in both northern and southern New Hanover County, she said. “In the Peedee aquifer, groundwater has declined more than 20 feet in the northern and northeastern area of New Hanover County since 1964. Both of these areas have been affected by industrial pumping for process supply and municipal water supply.”

Since the last geological survey study conducted in the New Hanover County area occurred 50 years ago McSwain said researchers cannot pinpoint exactly when saltwater intrusion began to move further inland or when levels dropped in areas of the aquifers.

“The tricky part of this study is that I don’t have a rate,” she said. “I only have a snapshot. This could have occurred within the last five years. It could have occurred 45 years ago.”

Public-utility supply competes with industrial, mining, irrigation and aquaculture groundwater withdrawals. As the county’s population and industry grows, so does the demand for drinking water. This is “one of the major issues facing the Coastal Plain area of North Carolina,” according to the report.

Long-term “over pumping” in the Peedee, Black Creek and Upper Cape Fear aquifers of the central coastal plain in counties north of New Hanover County have caused water levels in those aquifers to decline “substantially” during the past 30 years, the report states.

The state does not require New Hanover County to participate in the Central Coastal Plain Capacity Use Area, a group of 15 counties along the central N.C. coast where large groundwater withdrawals must first receive state permits.

Without such oversight industries like Carolinas Cement, a subsidiary of Titan America, which is proposing to build aplant in Castle Hayne, could theoretically pump indiscriminately from the aquifers.

An independent report released earlier this year examining the effects of dewatering – the process in which water is withdrawn during mining – concluded that mine dewatering could affect local wells in the Castle Hayne aquifer and, more critically, reduce recharge rates to the Peedee aquifer, causing an overall decline in water supply.

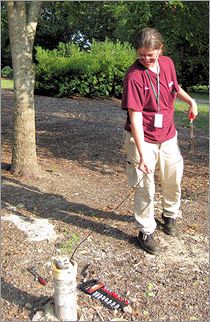

Kristen McSwain tests the groundwater depth. Photo: USGS |

The N.C. Coastal Federation-sponsored review by GeoReources Inc. also pointed out the likelihood of a broad cone of depression forming in the Peedee aquifer as a result of mining.

It is unclear what rules, if any, policy makers in Raleigh may come up with as a result of the new study.

Cape Fear Public Utility Authority officials, anticipating the potential of aquifer depletion and saltwater intrusion, have implemented plans to make sure their customers and future ones will have potable water, McSmith said.

“Number 1, we are migrating out of the Castle Hayne aquifer,” he said. “We find that the use of the Castle Hayne aquifer in our well field has some issues and we are spreading withdrawals from the Peedee aquifer across a wider footprint away from the Intracoastal Waterway. We will increase the amount of withdraw further away from the salt water and we will withdraw less from the Castle Hayne aquifer.”

The utility blends surface water and groundwater to provide water to its more than 65,000 customers. Blending helps reduce the demand on the Castle Hayne aquifer and optimize the resources of the Peedee aquifer, McSmith said.

“We have plenty of raw water source and treatment capacity to meet demands for the foreseeable future, and I’m talking decades,” he said.

The utility’s plant is designed to be able to treat saltwater if necessary, a measure McSmith said he doesn’t anticipate the authority having to implement.

Thanks in part to cost-conscious customers the utility’s water use has actually declined since the authority was formed in 2008. Customers have become more discretionary about watering their lawns and more people are installing efficient water fixtures in their homes, McSmith said.

“The areas closest to the ocean, to the Intracoastal Waterway and salty creeks are of greatest concern,” he said. “Those wells, we believe, are the most susceptible and are the ones that are influencing that intrusion the most.”