WILMINGTON — A cement company’s vow to adhere to stricter federal mercury emissions rules will not benefit the lower Cape Fear River, according to a university professor who has researched the water’s chemical contents.

Steve Skrabal, a chemistry professor and associate director for education at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s Center for Marine Science, said the mercury-impaired river does not need an additional mercury source.

Supporter Spotlight

“The main issue in my mind is that there is currently a mercury problem in the Cape Fear system,” Skrabal wrote in an email. “This is why there is an advisory for fish consumption in the Cape Fear and most other systems on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. A non-trivial mercury source should not be approved for our system while we still have a problem.”

Steve Skrabal |

That potential source is a proposed cement plant on the banks of the Northeast Cape Fear River in Castle Hayne, a rural community outside of Wilmington.

Titan America officials remain steadfast that the proposed facility will remain within EPA regulations as the company moves forward with plans to build the plant and operate a quarry on more than 3,000 acres in New Hanover County.

The federal National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants limits mercury emissions “potential to emit,” or PTE, at 21 pounds a million tons of clinker produced, Kate McClain, Titan’s corporate communications director, wrote in an email.

“The proposed plant could produce up to 2.19 million tons of clinker per year, which equals a PTE of 46 lbs. of mercury per year,” she said. “Keep in mind that this is considerably less than the 263 lbs. of mercury PTE allowed when Carolinas Cement was first proposed.”

Supporter Spotlight

In making Portland cement, clinker is small lumps or nodules produced by fusing together without melting limestone and clay in the kiln.

Intertox, a Seattle-based toxicology company that conducted an independent, peer-reviewed mercury study in 2008-09, concluded that the mercury emissions based on the 263 pounds “will pose nominal risk to the public health of the greater Wilmington community.”

“Today, the PTE of 46 lbs. is less than 1/5 of the original limit, so the potential impact is significantly reduced from the original Intertox study,” McClain said.

Intertox concluded that the total estimated dose of mercury a typical Castle Hayne resident “could encounter is less than the concentration of mercury in 1¾ teaspoons of canned like tuna fish per month.”

Carolinas Cement Co., a Titan subsidiary, paid for the study.

Methylmercury

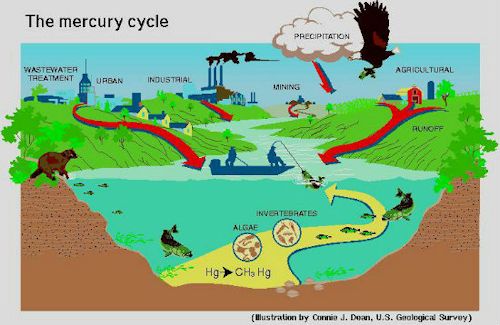

Mercury is emitted from many sources. In the environment, is converted to methylmercury, a dangerous neurotoxin. Graphic: USGS |

The greatest sources of mercury released into the atmosphere are stacks of coal burners and waste incineration, said Skrabal, whose wife, Tracy, is a scientist for the N.C. Coastal Federation. The environmental group is a leading opponent of the cement plant.

“In the Cape Fear region, the biggest sources were the Sutton power plant, the WASTEC trash burning facility, and the HoltraChem manufacturing plant which made chemicals for the adjacent International Paper plant in Riegelwood,” he said. “These sources don’t exist anymore.”

The HoltraChem plant closed in 2000 and the garbage incinerator in 2011. Duke Energy converted the Sutton plant to natural gas in 2013.

These old pollution sources, though, have long-lasting effects because the methylmercury they created is a dangerous neurotoxin that lingers in the environment for decades. The organic metal is a byproduct of burning fossil fuels, particularly coal. The inorganic mercury in the coal is released into the atmosphere when the coal is burned. The mercury particles then fall back to earth with precipitation. Microorganisms in the sediment of water bodies convert some of the mercury into its organic form in a process scientists like Skrabal call methylation.

The Northeast Cape Fear River, he noted, is particularly efficient at it. “It has warm acidic sediments with lots of organic matter to sustain the process of sulfate reduction. Sulfate reduction is the process whereby naturally occurring bacteria in sediments convert sulfate in water to sulfide,” Skrabal explained. “As a byproduct of this natural process, the organisms also convert some of the mercury to methylmercury. That is the crux of the problem.”

The organic metal works its way from the sediment up the food chain – small fish eat worms and insects in the mud, bigger fish eat them and so on and so forth. The mercury accumulates in the tissue of the fish with each meal in a process known as bioaccumulation. Long-lived predatory fish tend to have the highest mercury concentrations in their tissue. People who eat those fish are then are risk of mercury poisoning. That’s why the state health director has issued consumption advisories for various types of fish in all state waters and for king mackerel, swordfish, shark and tilefish from the S.C. border to Cape Hatteras.

“Methylmercury is typically not more than a percent or two of mercury in a system,” Skrabal said. “This is true in the Cape Fear also. But it still causes problems because it is the form that is bioaccumulated by many orders of magnitude as you go from water or sediments to organisms.”

Skrabal said researchers collected water samples on a monthly basis for about a year in the early 2000s.

A River Impaired

Titan opponents protested after the state issued an air permit to the company in 2012. Photo: WWAY-TV |

The Northeast Cape Fear River is classified mercury impaired by the EPA, a red flag for any potential new mercury sources as far as Cape Fear River Watch is concerned.

That group joins the ranks of other environmental organizations fighting to keep the proposed cement plant out of New Hanover County.

In a statement posted on its web site, Cape Fear River Watch argues additional atmospheric release of mercury “should not be allowed as it will further impair an already impaired water source and potentially further harm sensitive ecosystems proximal to the plant operations.”

The N.C. Division of Air Quality issued the company an air permit in late February 2012. In August 2013, the division agreed to extend the air permit for an additional 18 months at the company’s request.

Titan asked for the extension, citing that on-going litigation with environmental groups, including the federation, made it difficult to stick to the required construction timeline.

At the same time, the state modified the air permit’s limit for particulate matter emissions. Particle pollution includes acids, such as nitrates and sulfates, organic chemicals, metals and soil or dust particles. Smaller particles have greater potential for causing health problems because of their passage through the throat and nose directly to the lungs.

The modification allows for increased emissions, though company officials have stated the change is not expected to impact the proposed plant’s actual emissions and that the facility will operate within the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

McClain said the company has no plans at this time to request an additional air permit extension.

The company has yet to begin the federal environmental impact statement process.

“We plan on starting work on the EIS early next year,” McClain said.