A glimpse into the style of dress at the Lumina Pavillion at Wrightsville Beach in the early 20th century. Elegant attire suited fussy crabs minced Mayonnaire, creamed sweetbreads in casserole, soft-shelled crab au canape and roast Long Island duckling with kumquat marmalade. Photo: Wrightsville Beach Museum of History |

Supporter Spotlight

Supporter Spotlight

This is part a monthly series about the food of the N.C. coast. Our Coast’s Food is about the culinary traditions and history of N.C. coast. The series covers the history of the region’s food, profiles the people who grow it and cook it, offers cooking tips — how hot should the oil be to fry fish? — and passes along some of our favorite recipes. Send along any ideas for stories you would like us to do or regional recipes you’d like to share. If there’s a story behind the recipe, we’d love to hear it.

WRIGHTSVILLE BEACH — Seafood platters mounded with fried shrimp and fish, Tower 7 restaurant’s fish tacos and Roberts Market’s grab-and-go snacks seem forever woven into Wrightsville Beach’s dining culture, but forget tartar sauce, salsa fresca and tubs of pimento cheese 100 years ago.

Victorian ladies showed up to fancy dinners in lacy, white, cotton dresses. Their escorts wore tall, neck-binding collars, tailored jackets and shiny pocket watches in their fitted vest compartments.

The Wilmington Seacoast Railroad Co. began running its “Beach Car” in 1888. |

Elegant attire suited fussy crabs minced Mayonnaire, creamed sweetbreads in casserole, soft-shelled crab au canape and roast Long Island duckling with kumquat marmalade.

Over the past two years, Wilmington historian Elaine Henson has felt among the diners. She researched the history of Wrightsville Beach restaurants for a July program that was titled “A Century of Dining at Wrightsville: 1880s to 1980s.” She gave the presentation at the Wrightsville Beach Museum of History, next door to the N.C. Coastal Federation’s new satellite office and coastal education center.

“It wasn’t like it is today,” Henson said of yesteryear dining. “Not at all.”

For starters, diners didn’t walk from their beach houses or drive their cars to restaurants. Before there was public transportation to the beach, visitors, in their snazzy clothes, rode little skiffs for their “excursions” to the shore.

The first restaurants debuted in 1884 at Seaside Park and Pine Grove hotels, on Wrightsville Sound. When Wilmington Seacoast Railroad Co. in 1888 ran its “Beach Car” from downtown Wilmington’s Front Street to what’s now Harbor Island, and tracks were extended across Banks Channel to the beach a year later, eating places emerged quickly to serve a mushrooming market.

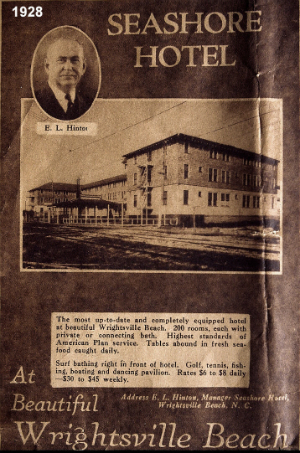

Wrightsville Beach was incorporated 1899. By then, at least four hotels sat seaside. The circa 1892 Hinton’s Café, inside Ocean View Hotel, came first, Henson said. A September 1892 Wilmington Messenger article congratulated owners E.L. and J.H. Hinton, who Henson noted also ran accommodations in Wilmington and Carolina Beach, for “the unrivaled manner in which soft-shell crabs, deviled crabs, picked crabs, shrimps, pigfish, clam chowder, etc., has been served to the delegation of epicurean visitors to the seashore.”

Hotels were hotspots for guests and day visitors alike.

The Seashore Hotel prized itself for serving fresh seafood caught daily. After the Great Fire of 1934, the Seashore Hotel was renamed the Ocean Terrace Hotel. After more damage from Hurricane Hazel and another fire, it was replaced by the Blockade Runner in 1964. Photo: Wrightsville Beach Museum of History |

Two hundred people attended the 1897 Seashore debut dinner featuring 32 selections including broiled summer trout with parsley sauce, pommes Parisienne, lemon pie and macaroons. An American history-themed 1916 Independence Day menu offered Plymouth rockfish with Lexington sauce, calf brains à la George IV and “revolutionary” crackers with young American cheese.

For $5, Hotel Tarrymore guests sampled “cuisine unsurpassed,” according to a 1905 advertisement. A humble-looking Tarrymore opened that year. By 1911, it grew grand peaks lit by long strings of electric lights. The kitchen served elegant French cuisine and local favorites like broiled Spanish mackerel, clam fritters, candied sweet potatoes and corn on the cob.

Running restaurant kitchens was not easy. Sans electric refrigeration, chefs required frequent train deliveries of ice and provisions. Cattle that supplied milk and meat grazed near the shore. A news report about one hotel fire mentioned yard chickens cooked by the blaze.

Sanitation was a challenge. The trolley line that opened in 1902 included a garbage car, Henson said. Flies, smelly ice boxes and water that tasted of decayed wood were among problems health inspectors found at one restaurant. On a 1919 night, a health inspector dining out was served spoiled fish and a fly floating in his iced tea.

Despite behind-the-scenes shockers, restaurants flourished and those in hotels inspired modern accommodations such as Blockade Runner. Built in 1964, the resort is about where the Seashore Hotel stood, Henson said. Blockade Runner’s early Ocean Terrace Room, which hosted dinner and dancing, served a 1965 Thanksgiving Day meal including a whole turkey “carved at your table, leftovers to take home,” for $2.95 per person.

The dining room’s Ocean Terrace name harked back to Seashore, which was renamed Ocean Terrace after it survived a 1934 fire. Fire hit again, destroying the renamed Ocean Terrace hotel in 1955.

Blockade Runner continues to honor its predecessor with its Ocean Terrace seafront rooms.

When authorities allowed cars on Wrightsville Beach in 1935, restaurant development surged and the quintessential fried seafood platter, so common today, made its lasting mark.

The Oceanic Hotel, built in 1905, was the most upscale hotel at Wrightsville Beach. It was the first stop at the beach for the trolley. The Oceanic had a restaurant with its own orchestra for the summer months. What you see in the photo is the hotel from the sound side with its romantic turret and spiral staircase. On the ocean side, there was an octagonal tea room right at the ocean’s edge. Photo: Wrightsville Beach Museum of History The Oceanic Hotel, built in 1905, was the most upscale hotel at Wrightsville Beach. It was the first stop at the beach for the trolley. The Oceanic had a restaurant with its own orchestra for the summer months. What you see in the photo is the hotel from the sound side with its romantic turret and spiral staircase. On the ocean side, there was an octagonal tea room right at the ocean’s edge. Photo: Wrightsville Beach Museum of History |

The Neptune, now named King Neptune, on downtown Wrightsville Beach’s Lumina Avenue and, at age 67, regarded as New Hanover County’s oldest restaurant, featured seafood and steaks “cooked to a king’s taste.”

Marina Grill, opened in 1946 in abandoned World War II Marine Corps barracks on the Wrightsville Beach Causeway, won a seal of approval from restaurant reviewer Duncan Hines, then “the American authority on good eating” rather than the cake mix king. In 1947, a Marina “deluxe” two-course seafood dinner, with a choice of one entrée – shrimp Newburg, fried frog legs and shad roe with bacon among them – and fries, clam fritters and coleslaw on the side, cost $1.50.

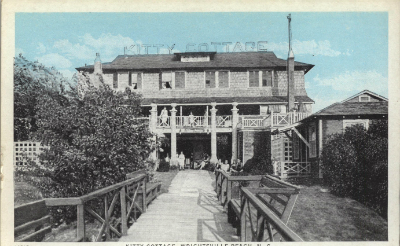

“Oyster roasts,” places that served steamed and fried seafood in ultra-casual settings were popular too, as were guest houses where lodgers slept upstairs and dined downstairs. Even as far back as the late 1800s, women managed some of the largest and most popular establishments.

Here is one of the original boarding houses where people slept upstairs and dined downstairs. Photo: Wrightsville Beach Museum of History. |

“It was one of the things a woman could do with a family if their husbands passed away,” said Madeline Flagler, Wrightsville Beach Museum’s executive director. “It was something you could do and do well and still have a real life.”

As beach life moved toward flip flops and ice-cold white wine, Wrightsville Beach restaurateurs went with the more casual flow.

The famous Lumina Pavilion (1905-1973) that early on staged formal ballroom dances hosted a grill and picnic tables. Nearby soda shops were favorite hangouts for teenagers.

Henson’s research and a lifetime of Wrightsville Beach memories uncovered a surprising number of food and drink places, including markets, “easily 100” over the century, she said.

Henson referenced residents and friends, old phone books, vintage post cards, newspaper reports and the collections of Wrightsville Beach Museum of History, the New Hanover County Public Library and historians Bill Creasy and Bill Reaves.

She and Flagler found no shortage of information – or interest.

“Different eating establishments are so much part of the culture here,” Flagler said. “You go to the beach, and you’re there all day, and somehow the food tastes better when you’re sunburned.”