Reprinted from The Outer Banks Voice

COINJOCK — The Mid-Currituck Bridge came close to being built. Now, its fate is more in doubt than it has ever been.

Supporter Spotlight

A plan was in place to pay for construction through a private-public partnership. All that remained was for the N.C. General Assembly to provide $24 million in gap funding – first estimated to be $15 million –to hold contracts in place until construction could begin.

But the legislature never approved the money. The partnership is still in place, but the private partner has the option to withdraw. A federal Record of Decision, the final step for a project first proposed more than 25 years ago, was never submitted.

Rep. Paul Tine |

Sen. Bill Cook |

Funding for the bridge was a casualty of the state’s Strategic Transportation Investment Law.

Supporter Spotlight

The Mid-Currituck Bridge was intended to link the mainland with the northern Outer Banks and relieve the huge weekend traffic jams that plague the Wright Memorial Bridge into Dare County. Without it, travelers to Corolla continue to cross the Wright Memorial Bridge, then loop north on two-lane N.C.12.

It was probably the most visible local project killed by the new law, but it was not the only one. A skyway in Wilmington was another high-visibility casualty. According to state Rep. Paul Tine, D-Dare, the N.C. Department of Transportation’s District 1, which covers northeastern North Carolina, will not see any projects move forward under the new ranking system.

Tine said the region’s highest ranked project is 121.

“By the DOT’s own admission, we are looking at over 20 years before we will see any funding from the statewide bucket,” Tine said in response to written questions.

Passed in the 2013, the law seeks to create an objective way to determine which highway projects go forward and in what order.

“The bill attempts to take politics out of transportation needs,” said state Sen. Bill Cook, a Republican who represents part of northeastern North Carolina, including the Outer Banks.

But if the law aimed to reduce or eliminate the politics, it failed to do so fairly, Tine and Cook both said. Although the law was passed with wide bipartisan support, neither of the local legislators supported it.

The amount of money northeastern North Carolina will lose is significant. Tine puts the figure at $340 million over the next five years.

North Carolina stands apart in the United States because all of its roads are maintained by DOT.

“We have 80,000 miles in our road system,” DOT Chief of Staff Bobby Lewis said. “In other states much of that would be . . . a county road system.”

In the past, all those roads competed for money through a tangle of categories: loop projects around major metropolitan areas competed with rural road improvement or new road construction. The result was a shifting of priorities and projects because clear guidelines had never been established.

Underlying everything was a growing funding crisis.

The new law is part of a larger national debate that every state and the federal government are confronting. The federal Highway Trust Fund is going broke.

An artist’s rendering of the proposed Mid-Currituck Bridge. Photo: NCDOT |

According to a Congressional Budget Office accounting in April, the trust fund won’t be able to meet its current obligations starting in fiscal year 2015.

The federal government and the states have underwritten road construction primarily through fuel taxes. The system worked well for many years, but a number of factors have come together to create the perfect storm of a funding crisis.

Fuel taxes have not changed for at least 20 years while construction costs have continued to escalate. Cars have become far more efficient, and people are driving less.

“There are serious transportation needs to the state that there are simply not enough funds to carry,” Malcolm Fearing, DOT Board of Transportation representative for Division 1, said.

In an effort to make the selection process more objective, the new law ranks projects in nine categories and adds criteria within each: benefit/cost, congestion, safety, economic competitiveness, freight, multimodal, pavement condition, lane width and shoulder width.

Language describing how to rate projects gives added weight to the ones effecting major metropolitan areas, critics say.

“What we are seeing is a system that is being set up to benefit the urban areas to the detriment of the rural areas,” Tine wrote.

Some of the language underscores Tine’s point.

The evaluation team, for example, uses commuting time by population as one measure. In a more densely populated area, commuting times will be much higher, leading to a higher ranking.

Of particular concern to coastal North Carolina is that nothing in the guidelines balances the needs of areas with tourist-driven economies.

In response to a question about using seasonal fluctuations in traffic volume, Don Voelker with DOT’s Strategic Prioritization Office wrote, “ . . . seasonal fluctuations in traffic volume are not part of the current scoring process. The group did look at seasonal traffic volumes; however, made the recommendation to use an average annual daily traffic volume number because it can be consistently applied across the State.”

Nor is there a reference to hurricane evacuation — often considered a critical element in evaluating highway environmental impact statements.

Fearing points out that some of the emphasis on urban centers is based on economic trends within the state.

“One of the things in a strategic plan for the whole state . . . if we attract people to our metropolitan areas, and continue to enhance their growth, that is where the growth is occurring,” he said.

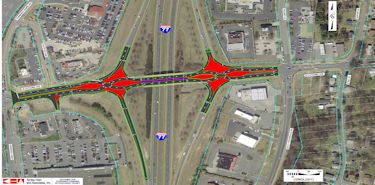

Coastal legislators fear that the new highway funding formula mandated by the legislature tends to favor urban projects like this one along I-77 near Charlotte over rural projects in Eastern North Carolina. Photo: Town of Cornelius |

Tine notes, however, that the law seems to generate winners and losers, and in this case the Outer Banks appears to be on the losing side.

The law creates three categories of projects: statewide, which will receive 40 percent of available funds; regional, receiving 30 percent of funds; and division needs, with 30 percent of funds.

Because of the language that the law uses to define statewide projects, Division 1 will almost always be competing for regional and division funds.

“To make matters worse, they added ferry replacement to our Divisional bucket,” Tine wrote. “So they reduced our funding and then increased the number of items we must pay from our division bucket . . . “

Tine’s fears about Division I projects may have merit. The sheer number of proposed new road construction projects listed on a DOT spreadsheet to show where projects rank puts the future of any new road construction in Division I, or coastal North Carolina, in doubt.

According to DOT, 339 statewide projects are vying for 40 percent of highway funds, 807 regional proposals are covered by 30 percent of the funds and the remaining 30 percent of the pot is allocated to 1,278 Divisional projects.

There is overlap among many of the projects, but it is clear that in a time of restricted revenues, only the very highest-rated projects will move forward.

The highest-ranked Dare County project is the DOT plan to add lanes and widen the intersection of U.S. 158 and N.C. 12 in Kitty Hawk. That project was once a part of the Mid-Currituck Bridge concept.

The five top-ranked road projects in the 20 coastal counties are intersection improvements on Western Boulevard in Jacksonville, Military Cutoff Road in Wilmington, N.C. 53 in Burgaw and Piney Green Road in Jacksonville.

Concerns about urban centers leading the rankings led DOT divisions in eastern North Carolina to opt out of the statewide system for regional and divisional projects.

“These divisions came up with a totally unique formula,” Fearing said. “Divisions 1, 2, 3 and 4 came up with a different methodology. Patrick Flanagan took this up. He’s the Planning Director for the Eastern Carolina Council.”

The regional planning council works with local governments on economic development and planning issues. Although specifically covering counties in southeastern North Carolina, the issues confronting those counties regarding the new formula were the same as the Division I counties.

The methodology that Flanagan developed strips out criteria that do not apply to rural districts — which is very much what Division I is — and places more emphasis on needs specific to them.

As an example, freight and multimodal evaluations are not included, but added emphasis is placed on lane and shoulder width.

“There are a lot of roads in this region that just aren’t up to federal standards,” Flanagan explained.

He acknowledges, though, that the specialized evaluation criteria will have little effect on which projects move forward, noting that the real effect may be to better understand regional needs.

Perhaps most importantly, the law does not affect current projects. The Bonner Bridge is not on the chopping block, nor are the planned bridges over Pea Island hotspots.

Although as now ranked, projects in Division 1, and especially Outer Banks, are very low on the priority list, a public comment period began June 26 and will through the week. The language of the law specifically gives added weight to local input on regional and divisional projects — 30 percent of the final score for a regional project and 50 percent for divisional.

The two hearings for Division I have already been held. But comments will continue to be accepted through July 25 on the STI Comment Card.

Language in the law does allows local governments to offset costs to DOT — probably through the sale of bonds, although how a local government would choose to contribute to the project is not specified. A contribution from a local government could have a significant effect on the benefit/cost formula.

There is also an acknowledgement from DOT officials that the rating system now in effect will have to be adjusted.

“We anticipate hurricane evacuation routes and seasonal fluctuations to be among the criteria considered and revisited in two years when the work group reconvenes to discuss ways to improve the data and scoring for the next update,” Voelker wrote.

Yet underlying everything is the same issue that has led to this point.

“There are way more project costs than there are dollars available,” Flanagan said.