RALEIGH — Try not to think about them as a complex series of interlocking guidelines, definitions, regulations and standards. Think about them instead as a collection of stuff you’ve got to put in three buckets.

The first bucket is for stuff you don’t need. The second is for stuff you know you need without question. In the third bucket goes the stuff you think you need — or thought you needed — but now you’re not sure.

Supporter Spotlight

For the next five years every state agency that promulgates rules will have to sort them — about 19,600 in all — into one of those three buckets, which are officially labeled by law as “unnecessary,” “necessary without substantive public interest” and “necessary with substantive public interest.”

Watershed rules like those for the Neuse River will be among the first up for review. Photo: NCSU |

Among the first in line and the only rules specifically named in the last year’s rules review legislation passed by the N.C. General Assembly are the state’s surface water and wetland protections. Roughly 400 individual rules in all, they cover a wide range of categories including water supplies, individual watershed rules like those for the Tar, Pamlico and Neuse rivers, rules on outstanding resource waters like those covering portions of Bogue and Core sounds and regulations on the land application of animal and human waste.

Since the law — the omnibus Regulatory Reform Act of 2013 — passed, the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources, or DENR, and the N.C. Environmental Management Commission, or EMC, have opted to put nearly all of its wetland and surface water rules into the third bucket, triggering a process that requires each rule to go back through the adoption process this time under new, tighter guidelines set up by the legislature in 2011.

Since the decision to require that nearly all the rules be re-adopted there’s been a growing worry among environmental organizations that the state has opened the door for industry to rewrite the environmental rulebook in one sweeping do-over.

Grady McCallie, a policy analyst with the N.C. Conservation Network who has been tracking the progress of the review, said the potential is there for interest groups to have another crack at rules that took years to work out.

Supporter Spotlight

He said he was not surprised given the legislative mandate that DENR decided to put nearly all the rules up for full review. “The way the legislature wrote the language it meant anyone who might be interested,” he said, adding that one bright spot is DENR’s review found that despite popular belief that there were not a lot of rules found to be “unnecessary.”

McCallie said the decision not only has the effect of re-opening established rules to change, but it represents a lot of work for an already overtaxed department. “The effect is going to be a massive workload,” he said.

Under the new system set up by the legislature, each rule now requires a fiscal impact analysis. That alone, McCallie said, is going to be costly. “Right now we have no estimate of how much this process is going to cost the state,” he said. “Are they going re-adopt the old rules or start from scratch? What’s the baseline?”

Grady McCallie |

The department, which has seen deep budget cuts in recent years and is pouring resources into work on coal ash, has yet to spell out what it sees as the direct costs of the review and re-adoption process.

DENR spokesperson Susan Massengale said the department anticipates it will take two to three years to complete the reviews and the re-adoption process. She said DENR does not intend to seek an additional appropriation.

This month, the first comment period focuses specifically on the decisions about how to classify the rules — which bucket they go in. After the EMC reviews the feedback from the public, it will make any adjustments to the list. In July, the plan for which rules to eliminate and which to send through the re-adoption process will go to the EMC’s water quality subcommittee.

Massengale said so far there have not been many comments on the department’s determination. “We haven’t had a whole lot of response so far and are still collecting comment for this part of the process until May 21,” she wrote in an email response to questions. “Most of those comments agree that the rules are necessary and have substantive public interest. We have gotten a few comments that suggest changes to the rules themselves and fewer still that disagree with our determination about a rule here or there.”

Massengale said all comments will be made public.

The Second Step

The full EMC is expected to vote on its final determinations in September, which starts the next step in the process, handled by the state Rule Review Commission, an obscure executive agency established in 1986 with the limited role of determining that new rules are legal, clear and necessary.

The commission added staff this year to meet its new mandate and the anticipated surge in work. It has scheduled a monthly intake of rule review and determinations from departments across state government through June 2019. Under the new law, the process is scheduled to repeat itself with every rule on the books going through a similar review and possible re-adoption every 10 years.

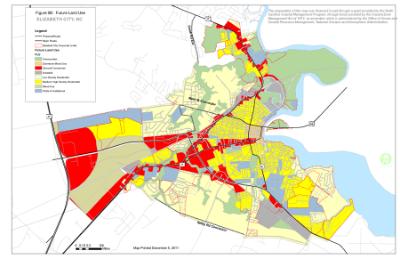

Land-use rules like those that guided this future land map for Elizabeth City will be the first CAMA rules that will be reviewed. Photo: NCDCM |

Surface water and wetland rules, which are under a legislative deadline to be completed in the first year of the new system, are on the commission’s October calendar. Other agencies and rules quickly follow.

According to Mike Lopazanski, chief policy analyst with the N.C. Division of Coastal Management, the first set of Coastal Resources Commission rules will be the CAMA Land Use Planning Requirements — the 7B rules — which are scheduled to go before the rules commission in December 2015. Lopazanski said the division expects to begin a review of the rules with the Coastal Resources Commission this fall. The remainder of the Coastal Resources Commission’s rules (15A NCAC 7H; 7I; 7J; 7K; 7L; 7M) will go through the process by January, 2018.

Abigail Hammond, legal counsel to the Rules Review Commission, said the commission’s schedule anticipates their first set of determinations and comments to be filed next month ahead of the commission’s July meeting.

The commission is charged with reviewing the work of the agencies, the comments and responses and sign off — or not — on the work.

“It’s hard to predict the amount of work,” she said. So far, she said, the schedule is on track. “It’s a new process,” Hammond noted, “but the legislation lays out clear rules.”

Part of that clarity is what happens once the commission signs off on an agency determination. By law, all rules in the necessary with substantive public interest bucket “shall be readopted as though the rules were new rules.”

Mary Maclean Asbill |

While that process, which sometimes can take more than a year, proceeds, most of the rules, especially those that enforce federal requirements like those in the Clean Air and Clean Water Act will stay in effect. Ultimately, agencies can choose to alter or change the rules or even end them all together.

Mary Maclean Asbill, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, said there’s a lot of concern about what happens once the rules start to go through a re-adoption process.

“It really remains to be seen what will happen in the long run,” she said. “Any kind of rewrite should not be extensive. We don’t want to open the rules up to a wish list from businesses.”

She said the state should exempt rules that have been recently adopted under the procedures in the 2011 law.

McCallie, said how open and how inclusive that process is will make a huge difference in the outcome. Right now, he said, it isn’t clear who will be at the table if and when rules get rewritten.

“Is it going to be a fairly formal process or do a set of interests just show up and meet?” he said.

“In the end, though, what is recommended and what makes its way into the state administrative code could be very different.

In addition, to setting up the new review process, the legislature which is not shy in spelling out just what certain rules should do, left itself an opt out, giving General Assembly’s Administrative Procedure Oversight Committee the authority to send anything it doesn’t like back through the process for another look.