First of two parts

A student measures an oyster at a N.C. Coastal Federation restoration project. |

Bundled up on a cold day at Jockey’s Ridge State Park, students from First Flight Middle School in Kill Devil Hills take turns matching larvae to the adults of different ocean species. As a part of a larger environmental education program with the N.C. Coastal Federation, this field trip to the beach is, for some of the children, the first time they have been to the state park that is just five minutes from their school. Energized by the wind and sounds of the beach, the students are excited to be out of their regular classroom environment.

Supporter Spotlight

But it turns out there is more in it for the students than just a fun trip to the beach. Recent research conducted by N.C. State University on middle-school students found that taking students outdoors significantly improves their environmental literacy, especially in the areas of ecological knowledge, environmental attitude and environmental behavior.

Moving the classroom outside, or as some have called it “no child left inside,” is gaining recognition as an effective strategy to improve environmental education. North Carolina ranks amongst the lowest in the nation in many scores of education success, including ACT scores and per-student funding. In an effort to address the state’s poor standings in environmental education, environmental researchers and educators developed the N.C. Environmental Literacy Plan.

“The whole point in environmental literacy is to equip kids with skills they will need to deal with environmental problems, such as climate change,” said Kathryn Stevenson, a Ph.D. student in the Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology Department at NCSU who led the research. “We wanted to get in there and assess what kids know, and what they don’t know.”

Funded by the N.C. Sea Grant and based on the recommendations from the N.C. Environmental Literacy Plan, Stevenson and her colleagues surveyed sixth through eighth grade students and teachers to assess factors that improve environmental literacy. They published the results in March in the online journal PLOS ONE

“What we saw from the research was that the kids seem to care a lot about the environment. But paired with the national average, their ecological knowledge was just O.K., and their cognitive skills had a lot of room for improvement,” said Stevenson.

Supporter Spotlight

The results showed that taking students outside helped to improve these weak areas, suggesting that the students learning about life stages on the beach in Jockey’s Ridge will learn better than if they had the same lesson in their classroom.

Students use a refractometer to measure the salinity and specific gravity of water. |

Taking students outdoors not only improves their cognitive ability, but also helps to connect them to the meaning of what they are learning. What is not yet clear is whether simply being outdoors improves a student’s ability to learn – the power of a little fresh air and sunshine – or if it is where you go when you are outside that matters most. Does a lesson on beach erosion taught in a sunny courtyard have just as much of a cognitive impact as one taught on a beach?

“That is a super interesting question that we are trying to figure out the answer to,” explained Stevenson, noting that this could mean that simply teaching a lesson in fresh air, regardless of subject matter, will increase the amount the students will get out of that lesson. “Environmental education does seem to correlate with academic improvement in general. All the teachers say they [the students] come alive.”

This seems especially true for minority students.

“Taking kids outside gets them to care more about the environment, but it seems to make Hispanic and African-American students care more,” explained Stevenson.

Both of those groups initially had lower ecological knowledge and cognitive skills. However they showed the most improvement from spending class time outside, suggesting that outdoor learning may be one way to close the gap between minorities and Caucasians in environmental literacy.

It isn’t just taking students outside that makes a difference. One of the strongest indicators of improving environmental awareness in all students was the level of training and experience in the teachers. Students who had teachers who had a master’s degree and three to five years of teaching experience improved more over the course of a semester than those who had teachers with less educational training and either fewer or more years of experience in teaching. In addition, teachers who used establish educational curricula, such as Project WET, had students who demonstrated better environmental literacy, particularly in the weakest area of cognitive skills.

But for all of these criteria, it seems there is a critical age where environmental education is going to have the greatest impact.

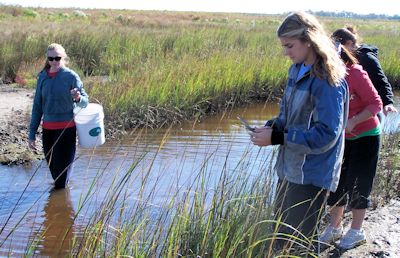

Students gather marsh grass seeds at the federation’s North River Farms wetlands restoration project. |

“Middle school seems to be a great intersection of cognitive skills, and they are young enough that they still have a sense of awe. You gotta get them while they young. Sixth graders learned a lot faster than eighth graders,” said Stevenson.

Making an effort to take these children outside could also provide them with a much needed breath of fresh air, notes Stevenson. “Part of the reason we may have found such an effect with them being outside was because this might be their only time outside,” she said. “At least anecdotally, many students seem to lack a connection and experience with nature.”

Stevenson is continuing to research environmental literacy in students in North Carolina. Her current research is focusing on perceptions of climate change in coastal N.C. students to try to understand some of the factors that influence how students perceive climate change issues.

On the coast, the lessons learned from Stevenson’s research are already in action. Connecting students with their environment is exactly what the federation hopes to do with field trips such as the one to Jockey’s Ridge.

As Sara Hallas, a coastal education coordinator for the federation explained, “I am happy to see this in formal results because it is definitely what the Coastal Federation’s approach has been all along — taking students outside. We don’t have the scientific findings, but we see the same things. You give them a fresh-air environment and it makes a huge difference.”

Tuesday: The N.C. Coastal Federation leaves no kid inside