ENGELHARD–With numerous bureaucratic hurdles finally cleared, an innovative wetlands restoration project led by the N.C. Coastal Federation is about to begin on thousands of acres of Hyde County farmland.

“The actual physical work is getting ready to start,” said Mac Gibbs, a federation board member and recently retired Hyde County North Carolina Cooperative Extension Director. “It’s probably been five years since we started this project.”

Supporter Spotlight

A collaboration between farmers, the federation, N.C. State University, USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service and several other state and federal nonprofits and agencies, the two complementary projects are designed to store and filter millions of gallons of stormwater runoff from farmland north of Engelhard.

In the process, 2,750 acres of wetlands will be restored, and millions of gallons of farm drainage into tributaries of the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds will be substantially reduced.

Canals such as this one convey millions of gallons of farm runoff from fields and into coastal waterways. This project offers a solution to this problem. |

“We’re excited about the strong partnership that has developed and the opportunities to dovetail the goals of the landowner’s management needs with water quality and habitat restoration,” Erin Fleckenstein, the federation’s project administrator, explained.

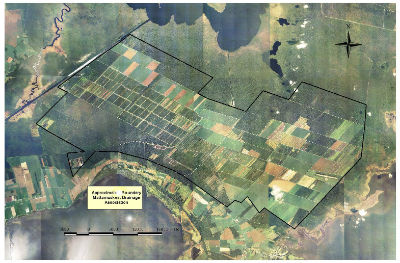

The land is located within the 42,500-acre Mattamuskeet Drainage Association that manages storm water through canals to the Pamlico Sound and the Intracoastal Waterway. The federation is working with local landowners, including Hyde County and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to restore the natural hydrology of the land, resulting in improved estuarine water quality for finfish and shellfish.

An aerial view of the Mattamuskeet Drainage Association, where the work is taking place. Map: Claude Long |

The drainage district is surrounded by environmentally sensitive areas: Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge, Gull Rock Game Lands, and the Long Shoal and Alligator rivers.

Supporter Spotlight

“The landscape is so flat,” said Fleckenstein. “The lands within the drainage association are managed by a series of pumps and canals that were dug from the ‘50s to the ‘80s. This has altered the historic hydrology of the area and has moved more water to the east than originally flowed.”

Major canals are spaced every mile, with smaller canals in between.

“This is typical of much of eastern North Carolina. It’s a very modified and engineered system,” she said.

When the restoration is complete, these pumps will only be used during hurricanes or other severe weather events. Photo: Christine Miller |

Gibbs had acted as an intermediary between Hyde farmer Wilson Daughtry, owner of Alligator River Growers, and the federation after Daughtry had expressed interest in management of the runoff from his land. In 2003, Gibbs helped bring together stakeholders to discuss the details of how the land, the farmers, the wetlands, the fish and the waterways could share the benefits if the field drainage was managed properly.

“When they left that meeting,” he said, “they were really excited.”

In a complex plan designed by assistant professor Mike Burchell and a team of engineers at N.C. State’s Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, the canals that intersect the farmland will be retrofitted with a number of pumps and weirs to control stormwater flow during heavy rains, redirecting the water into a created wetland rather than pumping it off the farmland into the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds.

The work on the projects will include construction of ten swales and two sloughs that foster water flow through the wetlands, allowing the natural nutrient removal process. The project will also core over 14,000 feet of dikes around the perimeter of the project, which will ensure that the restored wetlands retain the redirected water. Drainage water will be held in three shallow receiving areas adjacent to the farmland, and overflow will slowly seep into historic paths north toward Alligator River refuge.

As a result, millions of gallons of polluted drainage from farm fields will be kept from going into the waterways and harming fish. The water will instead be filtered through the soil and harmlessly used by vegetation. In the process, wildlife gain habitat and farmers gain better water management and protection from crop damage caused by salt-water intrusion.

“The perimeter pumps will only be activated during heavy rainfall,” Gibbs explained. “Those surges are what hurt water quality.”

Typically, the area gets 50- to 55-inches of rainfall a year, he said, but 35 of those inches get taken up by plants or evaporate- leaving just 16 inches a year to be pumped.

“You can go a month,” he said, “and the pumps would never come on.”

The two projects moving to construction have received nearly $2.6 million in funding with $1.3 M in grants coming from the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, $1 M from the Natural Resources Conservation Service Wetland Reserve Program, and a $74,989 grant from the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership (APNEP), which awards project money provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The remainder was funded by matching state grants and in-kind resources.

“Projects like these can restore vast swaths of hydrology along the coast, helping to prevent or slow the runoff of nutrients and other pollutants into the sounds,” Jim Hawhee, APNEP policy and engagement manager, said in an e-mail. “This project has the added benefit of supporting the area’s farmers by improving their capacity to manage water on and around their fields.”

After the project is completed in the coming year, the association’s pump use will be logged. The University will also model the pollutant removal rates as part of their work on a larger EPA watershed restoration plan.

Much knowledge gained from an earlier federation restoration project at North River Farms in Carteret County will be applied to the Hyde project, Fleckenstein said. Many of the same groups were involved, and we found that the Carteret site benefited most over time by restoration of the natural hydrology.

“We learned a lot of lessons of how to restore wetlands on a large scale,” she said.

About 15 years ago, when the federation began studying ways to restore oyster populations, it soon became apparent that the best way to restore the water quality in the sounds was to address the landscape modifications and runoff carrying polluted water into the estuaries.

“These canals, even in light rainfalls,” Fleckenstein said, “can transport bacteria, sediments and nutrients into our coastal waterways.”

The Mattamuskeet district was promising for restoration because of its large tracts of land and the willingness of the landowners to work with the federation.

Gibbs said that Daughtry and other farmers saw the writing on the wall and realized that it was to their benefit to be proactive, rather than having some agency dictate how to manage their land.

“This is a very environmentally sensitive area,” he said. “It’s easier to help set the standard rather than being told what the standard is.”