Then: This is the last photograph of the RMS Titanic afloat. It shows the Titanic departing Southampton, England, on April 10, 1912. You can see a tug boat on the Titanic’s starboard side and the sailors on the prow throwing off the bowline. |

Now: <class=”caption”>More than two miles down, the ghostly bow of the Titanic emerges from the darkness on a dive by explorer and filmmaker James Cameron in 2001. Photo: Walden Media, National Geographic Society |

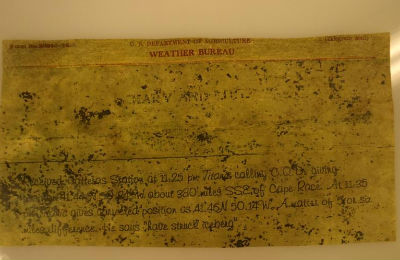

RALEIGH — A stained scrap of yellowed paper with remarkably neat handwriting and a horrifying message might be overlooked among the dazzling detritus displayed in “Titanic: The Artifact Exhibit” at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences.

But the telegram that recorded some of the worst news in history is a rare new Titanic discovery and the most direct link to the state.

Supporter Spotlight

“Received Hatteras Station at 11:25 p.m. Titanic C.Q.D,” it says, using the mariners’ distress code. “. . . . He says ‘have struck iceberg.’”

For one more month, museum visitors can see the original log page of the chilling communication sent by the RMS Titanic on April 14, 1912, as well as about 240 other artifacts that help illustrate the spectacular nightmare experienced by passengers on the luxury British passenger liner.

“It’s one of the earliest, if not the earliest,” Albert Ervin, the museum’s special exhibits coordinator, said of the message recorded at the U.S. Weather Bureau Station in Hatteras, “because the time that we typically hear that the Titanic hit the iceberg is 11:38 or 11:40. “

Ervin said it is not clear if the telegram was reflecting a time zone difference. Officially the vessel began sinking at 11:40 p.m. and disappeared under the sea at 2:20 a.m.

The log page of the Hatteras telegram, the only artifact in the exhibit that did not come from the vessel, was a last minute addition that brings the tragedy to our shores.

Supporter Spotlight

“I’m really glad we were able to get it loaned to the exhibit,” Ervin said. “It really ties it to here – to where we are.”

Consistent with other Titanic tales of happenstance, the document was nearly lost forever. In fact, even after it was pulled out of a wall, rolled up with old newspapers, when the weather station was being restored in 2005, it stayed undetected in deep freeze for about six months, said Doug Stover, historian for Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

When he went back to examine the sheets of paper ripped from the station’s old log books, Stover said, he had to strain to read the barely-legible writing. Suddenly he stopped.

“I noticed right away it said ‘Titanic C.Q.D.,” Stover recalled. “At that point, I said, ‘Man, we’ve got some pretty good documents.’”

Immediately, the Park Service sent the log page to its conservator in Harper’s Ferry. The restored document was later returned to the Roanoke Island storage facility for about 18 months, until someone remembered in March 2012 that the centennial anniversary of the Titanic sinking was coming up the following month.

Although it is now open to the public as a visitors’ center, is the old weather station lacks proper cases and security for such a historic item.

The U.S. Weather Bureau Station in Hatteras received the first telegraph from the doomed ship at 11:25 p.m. on April 14, 1912. It is now among the 240 Titanic artifacts on display at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences. |

The Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum, a state attraction in Hatteras that memorializes the 400-year history of shipwrecks off the coast, was the logical place to display the log page.

“We said, ‘Absolutely! We’d love to,’” said Joseph Schwarzer, director of the N.C. Maritime Museums. “We put that exhibit together in a little over two weeks.”

Schwarzer said that after a century of unflagging interest in the Titanic, it is unusual to find any new information related to the tragedy. And the transcription of the Marconi radiogram, he said, was especially fascinating.

“The fact that it was picked up in Hatteras is stunning,” he said. “It must have been a very clear night.”

Situated just off treacherous Diamond Shoals, the station, more than 1,000 nautical miles away from the doomed ship, was one of the few that was manned 24 hours a day. The same message, which described the Titanic’s position as 380 miles south-southeast of Cape Race, was also recorded at the Cape Race Marconi Station in Newfoundland, Canada.

Schwarzer said that it was one of the last times that “CQD” was transmitted as a distress signal.

Wireless telegraphy had been used for ship communication since the last days of the 19th century, and by 1904 most British ships were equipped with wireless, according to a 1997 article in the Telegraph Office Magazine. The letters CQ, meaning a general call to all stations, was already in use by land-based telegraph operators and was soon being used by ships and shore stations.

In 1904, the article said, the Marconi radio company adopted “CQD” as a distress signal. Although the term is often interpreted to mean “Come Quick Danger,” or “Come Quickly Distressed” – as a Park Service press release had explained –the letters more correctly mean, “All stations, Distress.”

David Sarnoff told the telegraph operator in Hatteras to stop clogging the lines with foolish messages about the sinking ship. He would later found RCA. Photo: Wikipedia |

“In the U.S. Senate hearings following the Titanic disaster,” the article said, “interrogator Sen. William Smith asked Harold Bride, the surviving wireless operator, ‘Is CQD in itself composed of the first letters of three words, or merely a code?’ Bride responded, ‘Merely a code call sir.’”

The better known SOS was officially ratified in 1908 because the …—… code was easy to transmit and understand. Its letters also have no specific meaning, despite being commonly interpreted as “Save Our Souls,” or “Save Our Ship.”

Recorded distress calls from the Titanic started out using only “CQD” and were later interspersed with “SOS.”

When the early message from the Titanic was forwarded from Hatteras to the New York office of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co., Schwarzer said that the manager, David Sarnoff –the future founder of RCA, scoffed at the idea that the unsinkable Titanic was distressed. Assuming the radio operator was drunk, Schwarzer said, Sarnoff forbade any further messages like it. Consequently, a second distress message sent from the S.S. Carpathia – the vessel that later carried survivors to New York – was never forwarded.

A Web site called “The Titanic Radio Page,” written by Glenn Dunstan, managing director of Dunstan and Associates, a marine communications company, provides extensive detail about the ship’s radio operation and the wireless messages sent to and from the Titanic.

In an e-mail, Dunstan, who described himself as a communications engineer and former ship’s radio officer, said that most of the information on the site came from his own research and his background.

According to transcriptions of the messages on Dunstan’s site, the first distress message was sent at 12:15 a.m., Titanic time.

Several distress calls were sent out at 12:25 a.m. including a position correction noted in the Hatteras transcription.

One particularly dramatic transcript of a 12:25 transmission conveys the growing urgency:

“Carpathia calls Titanic and says ‘do you know that Cape Cod is sending a batch of messages for you?’”

“Titanic says, ‘Come at once. We have struck a berg.’”

“It’s a CQD OM (it’s a distress situation, old man.)”

“Carpathia says, ‘Shall I tell my Captain? Do you require assistance?’”

“Titanic says, ‘Yes, come quick.’”

Another message at 1:27 a.m. reflected the dire straits:

Then: The U.S. Weather Bureau Station in Hatteras as in appeared in 1903. Photo: National Park Service |

Now: The old weather station has been remodeled and is now a visitors’ center at Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Photo: National Park Service. |

“Titanic says, ‘We are putting the women off in the boats.’”

Of the 2,224 on board, 1,514 died.

Schwarzer said that the Hatteras document is the sole remaining original station log from that telegraph. He added that he expects that it will be returned to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum when the exhibit closes in Raleigh.

The exhibit includes such items as the ship’s bell, portholes, dinnerware, passengers’ clothing and bottles of perfume. The log page may appear unremarkable. But in some ways, it freezes time like no other artifact.

“The significance of the telegram is it is physical evidence of that very moment when they realized the ship was not going to be saved,” Schwarzer said. “To the best of my knowledge, that’s the only thing we have that captures that moment.”

Visitors at the Raleigh exhibit, rather than being handed a ticket, are provided with a replica of boarding pass with a passenger’s name on it. They are then guided through replicas of parts of the ship. A volunteer interpreter portrays the captain. There is even a manufactured “iceberg” that can be touched. At the end of the exhibit, the “passengers” learns their fate.

Ervin said that the artifacts in the exhibit are a portion of the 5,000 artifacts retrieved by RMS Titanic Inc. from the debris field during eight expeditions. The recovered items were not taken from inside the remains of the ship, which was discovered in 1985.

In addition to the log page, there are other North Carolina connections with the Titanic, Ervin said. Since the ship was officially a mail carrier – RMS stood for Royal Mail Ship – mail was being transported from Europe to the U.S. One of the postal workers onboard was from Roxboro, N.C.

“He died on his 40th birthday,” Ervin said. “He went down saving the mail.”

Ervin also said that the great niece of a couple and their son who all survived the Titanic disaster grew up in Raleigh and wrote a book about her relatives’ experience. The woman, Julie Hedgepeth Williams, has given a presentation at the museum.

The exhibit also includes a piece of the actual hull that people can touch, and seven cases with artifacts that belonged to six passengers and one man who missed the boat but whose luggage was carried onboard.

But it’s the stories attached to the artifacts that makes the exhibit so compelling, Ervin said. And the Hatteras telegram is the opening line of the human drama that ensued that morning 101 years ago.

“I think people are really surprised and fascinated,” he said, “that there’s that North Carolina connection.”