RALEIGH — A resolution up for a vote next week by the Dare County commissioners and a position paper from a regional water resources group in Onslow County are the latest indications of the fast-growing coastal opposition to using coastal aquifers to eliminate wastewater from hydraulic fracking.

The position paper by the Onslow Water Resources Group says lifting the ban on the use of injection wells for wastewater threatens coastal aquifers. The group, which is made up of the Onslow Water and Sewer Authority, Jacksonville and Camp LeJeune, was reacting to Senate Bill 76, which would lift the decades-old ban on injection wells. A provision in the bill exempts “water produced from subsurface geologic formations during the extraction of natural gas, condensate, or oil in North Carolina” from the types of discharges banned in injection wells.

Supporter Spotlight

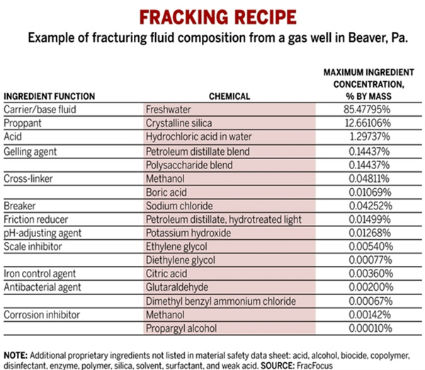

Fracking companies pump millions of gallon of water and toxic chemicals into the ground under high pressure to fracture the bedrock and release the natural gas. They prefer injecting the used fracking water into deep wells for disposal. Hydrologists have said that the geology of the state’s Piedmont, where most of the fracking will likely take place, isn’t conducive to injection wells. The coastal plain, scientists say, would be the most likely part of the state where such wells could be used, raising the specter of tanker trucks hauling the toxic brew to the coast for disposal.

Fracking companies pump millions of gallon of water and toxic chemicals into the ground under high pressure to fracture the bedrock and release the natural gas. They prefer injecting the used fracking water into deep wells for disposal. Hydrologists have said that the geology of the state’s Piedmont, where most of the fracking will likely take place, isn’t conducive to injection wells. The coastal plain, scientists say, would be the most likely part of the state where such wells could be used, raising the specter of tanker trucks hauling the toxic brew to the coast for disposal.

“The coastal groundwater system is complex, and the injection of liquid wastes into this system would prove to be detrimental,” the Onslow group states in its paper, which it has sent to the N.C. General Assembly. “There are essentially no unusable portions of the groundwater system in the Coastal Plain, and targeting the saline portions as waste disposal reservoirs is based on lack of understanding of the value of the resource to the current and future viability of the region.”

The bill, which passed the N.C. Senate on Feb. 27, could have a more difficult time in the state House where Rep. Rick Catlin, R-New Hanover, a hydrogeologist and environmental engineer, and others have taken issue with the injection well language. Catlin said last month the House would take a hard look at the implications of lifting the ban on wastewater in injection wells.

The bill has yet to be heard by a House committee. Its first scheduled stop is in the House Committee on Commerce and Job Development with hearings also likely in the House Environment and Finance committees.

Richard Spruill, a hydrologist at East Carolina University, helped to craft the Onslow position paper and has worked with Dare County and other local governments on similar resolutions. He said the use of injection wells for the wastewater that’s spelled out in the legislation could jeopardize a critical water resource for the coast.

Supporter Spotlight

“Throughout the entire coastal plain we rely on the aquifers,” he said.

Richard Spruill |

Only Greenville, Kinston and Wilmington have significant surface water reservoirs, he said. “Everybody else survives on groundwater from coastal plain aquifers,” Spruill noted.

Contrary to the notion that the saltwater aquifers on the coast are unused and therefore an acceptable place for the wastewater, Spruill said several communities are tapping aquifers that are prospects for the injection wells. Saline aquifers are used as drinking-water sources in Pasquotank County, Rodanthe and Waves in Dare County, Ocracoke Island and Emerald Isle and are seen as potential sources in many other places.

Spruill said that the Marine Corps’ concern is based on the potential it sees in using saline aquifers. Camp Pendleton in California recently installed a reverse osmosis plant.

In addition to opposition in Dare and Onslow counties, Currituck County and Wilmington have passed resolutions calling on legislators not to allow the coasts aquifers to be used for fracking wastewater.

The state banned the use of injection wells for wastewater in 1972 after contamination of the Black Creek Aquifer near Wilmington by Hercules Inc., which had been pumping industrial wastewater into injection wells.

Rick Shiver, who served as head of the state’s Division of Water Quality in Wilmington, and was part of a team that worked on the state’s response to Hercules, said the complexities of the coastal aquifer can’t be overlooked.

“Well injection of wastewater is really tricky business,” he said. “It’s one thing to extract water and another thing entirely to inject wastewater.”

Further complicating the issue, Shiver said, is that that composition of the fracking wastewater has been closely guarded by industry.

“How can you make intelligent decisions about well injection if you don’t know what’s in the wastewater?” he asked.