Tuckerton, N.J., seems adrift at sea after Sandy passed on Oct. 30. Can residents of the Jersey shore expect more of the same in the future? Photo: Coast Guard.

NEW YORK — In the aftermath of a storm that left more than 100 dead, over 8.5 million without power and caused an estimated $50 billion in damage, scientific experts and coastal residents alike are grappling with the portent of Superstorm Sandy.

Supporter Spotlight

Was this an incredibly damaging but incredibly rare strike on New York and New Jersey? Or is Sandy a harbinger of things to come, of a climate system driven to extremes by manmade greenhouse gas emissions?

For scientists convinced that global climate will undergo dramatic changes in the coming decades, extreme events like Sandy serve as something of a flashpoint. On the one hand, there is always a probability, however low, that an extreme event will occur within a given year. On the other, a warming climate fundamentally alters the probability of such extreme events.

Sandy’s Track and Surge

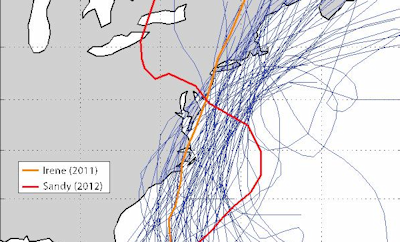

The track of Hurricane Sandy (red line), Hurricane Irene (orange line), and all tropical storms and hurricanes from the NOAA Hurdat2 historical database that crossed within 3° latitude and 5° longitude of Long Island, New York (blue lines). |

Conflating the issue is the very unusual track of Sandy. Forming as a depression in the Caribbean Sea on Oct. 22, Sandy strengthened into a late-season hurricane while heading northward through Jamaica, Cuba and the Bahamas. Off the coast of the Carolinas, Sandy interacted with a low-pressure system over the eastern United States, transitioning into a large and powerful hybrid storm before taking a westward turn into southern New Jersey on Oct. 30. Historically, most storms in this region, including Irene in 2011, have tracked to the northeast.

“There is no storm like it in the historical database,” noted Adam Sobel, professor of applied physics and applied mathematics at Columbia University and an expert on tropical meteorology. “The track was a worst-case scenario for New York City.”

Strikes by tropical systems on New England are, by themselves, not usual: tropical storm or hurricane landfalls along the coast between New Jersey and Massachusetts occur about every six to 10 years, according to a study published in 2007 in the Journal of Climate. But the storm surge from Sandy in New York City was likely larger than any storm in recorded history. A study published this year by Ning Lin, Kerry Emanuel and colleagues in Nature Climate Change suggests that the storm surge from Sandy was a once in 700 years event .

Supporter Spotlight

The Attribution Paradox

Adam Sobel |

Kerry Emanuel |

Joerg Schaefer |

Any search for a link between Superstorm Sandy and global climate change is hampered by a fundamental issue: Sandy was just one storm. And in the realm of noisy weather patterns, practically anything is possible given enough time, even without climate change.

“There are two logical possibilities,” said Emanuel, professor of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “One is that we were extraordinarily unlucky, and Sandy was a very rare event that we just happened to see this year. The other is that some change in the system has made events like this more probable.

“The big problem is that Sandy was a hybrid event (a combination of a hurricane and a nor’easter), and we haven’t done our homework on hybrid events,” Emanuel continued. “It’s impossible to know without more work.”

On the link between Sandy and climate change, Sobel is “skeptical but not dismissive”.

“It’s very hard to connect one event to climate,” he said. “But we’ve had two storms [Irene and Sandy] in two years and this track that’s never happened before in 150 years. We have to have an open mind when trying to determine the links between climate and severe weather events, even if we don’t yet understand all of them.”

For Joerg Schaefer, research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, proving the influence of climate change on Sandy is “putting the burden of proof on the wrong shoulders”.

“Everything behaves as we’d predict in a warmer world,” Schaefer said, citing the record loss of Arctic sea ice this summer as the latest in a litany of global weather extremes over the last decade. “The question needs to be turned around: Can we prove that climate change did not affect Sandy?”

As longtime residents of coastal areas can attest, hurricane-prone regions have witnessed dramatic increases in population, population density and development over the past decades. All have led to an intensification of the damage incurred from storms, even if the storms are not getting stronger. But add stronger storms on top of this, and the losses mount precariously.

“Over the last 100 years, the vast majority of the increase in hurricane damage is from demographics, not climate”, noted Emanuel, who studies hurricane losses and climate change. “But the two are multiplicative, not additive.”

“Even 150 years ago before CO2 was rising, the Jersey Shore, Battery Park and the Rockaways were risky places to develop,” said Schaefer. “But what climate change does is enhance the risk.”

Future Trajectories

How You Can HelpResidents of the coastal communities affected by Sandy in New Jersey and New York are still suffering nearly a month after the storm. And winter is coming fast. To help those in greatest need, please consider donating to: |

Going forward, Emanuel, Schaefer and Sobel agree that extreme events may become more likely due to anthropogenic climate change. The modeling work by Lin, Emanuel and colleagues suggests that the probability of a Sandy-sized storm surge event, a once-in-700 years event today, could increase to better than a once-in-300 years event by 2100, owing to sea-level rise and an increase in the strength of hurricanes from climate change.

“The right question to ask is, ‘Do we have a good reason to expect that the probability of an event like Sandy will increase in a warmer climate?’ CO2 is pushing us in one direction, on top of what the variability is, which may make extreme events like this more probable,” said Sobel.

“There should be a presumption of some unknown degree of climate influence on unusual weather by this point,” continued Emanuel. “It’s a question of how we should treat risk.”

If there is risk for more frequent or stronger hurricanes, then there is at least one silver lining in Sandy: The hurricane forecasts are better than they have ever been, thanks in no small part to decades of government funding for basic and applied research. “In Katrina, the forecast was very good and in Sandy, the forecast was uncannily good,” noted Sobel. “These were directly the result of long-term, government-financed improvements in forecasts and models”.

In the meantime, the question on everyone’s mind is obvious: When will the next Sandy strike? “I don’t know whether we have any better ability to predict that now than we did a year ago,” said Sobel.

“I don’t want to make predictions, but we’d be smart to start preparing,” he said.