Reprinted with permission from Susan’s Blogue

Louis T. Moore and Lorna Doone. Photo courtesy of Peggy Moore Perdew. |

“Trees are a God-given asset which require a century to mature, and which can be destroyed within a half hour when there is a plan to do so.” — Louis T. Moore

WILMINGTON — Louis T. Moore (1885-1961) had a lifelong fascination with trees and was a pioneer in their conservation. His interest sprang from his sensitivity towards natural beauty that colored his career green long before the word took on its present meaning.

Supporter Spotlight

The Wilmington native’s love of trees was encouraged during his college years at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill when William Chambers Coker, the legendary tree enthusiast, was teaching botany and creating the University of North Carolina’s Coker Arboretum.

Moore returned to his hometown in 1906 and became city editor of the Wilmington Dispatch. Due to an earlier bout with polio that had left him with a paralyzed foot, he remained in Wilmington during World War I.

Named as secretary of the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce in 1921, Moore worked tirelessly for the material good of the sleepy North Carolina port by waging campaigns to further the regional economy.

He lobbied to deepen the Cape Fear River channel, dredge an Intracoastal Waterway link, improve connecting corridors and build the city’s first river bridge. Through his speeches, voluminous correspondences and national magazine articles he recruited businesses to the area. His efforts helped existing institutions, too, like maritime shipping companies and the mighty Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, headquartered in Wilmington throughout his career.

While the business side of Moore entailed preserving the area’s legacy of commercial strength, the poet within studied and celebrated its various natural wonders like few people had before him. Many of the thousand panoramic photographs he took from 1921 to 1939 capture southeastern North Carolina’s lush environment. Though trees would become his focus, other living treasures caught his eye, too. The most unusual specimen was the carnivorous Venus flytrap, which he photographed and championed long before measures were taken for its protection. His steady efforts helped fuel a Cape Fear Garden Club drive during the 1950s to outlaw commercial sales of the plant.

Supporter Spotlight

The grand old trees of Hilton where Cornelius Harnett’s home “Maynard” once stood. Photo: N.C. Dept. of Conservation and Development. |

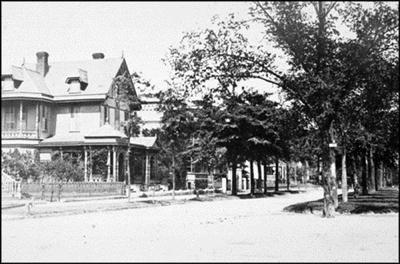

The trees of Market Street, circa 1920. Photo: Fales Collection, New Hanover County Library. |

Moore also wrote about the beauty of daffodils, camellias and azaleas, but it was the subject of trees that caused him to become enflamed. If anything other than an act of nature felled one of them, Moore had a tendency to spew words like a sawmill discharging wood chips. Trees were far more than regal beauty and grace to him. They marked time for us as humans and were community treasures. The oldest trees are silent witnesses to centuries of change, drama and, sometimes, mindless development. A precious few seem to become characters in the tale of the lower Cape Fear.

Moore’s loudest, longest tree campaign came about in an attempt to save hundreds of live oaks that once graced Wilmington’s downtown avenues. By the late 1940s, Third Street, a leg of U.S. 421, still boasted some grand oaks, but heavy oil truck traffic and a grid of utility poles had further compromised their aesthetic contributions. Moore and his allies called the byway “Gasoline Alley” and “South Pole Street.” Market Street, an intersecting east-west corridor, was another proverbial tree-lined boulevard until city fathers voted to widen it, and this raised Moore’s ire as well.

Moore and a handful of fellow progressive thinkers went on the warpath. “I remember how upset Daddy was when they cut down the pretty trees in the plaza on South Third Street and Market Street,” said Moore’s daughter, Peggy M. Perdew, in 2008. “I thought he was going to have a stroke. One of Mother’s friends watched him talking about this occasion and said it was ‘just like witnessing the eruption of Mt. Etna.’”

Operating as chairman of the New Hanover County Historical Society, Moore went before a joint meeting of the N. C. Highway Commission and Wilmington City Council to protest. He called the officials “dictators,” as a large crowd cheered him on and as he accused the antagonists of having “no interest in the community.” Moore said their disregard for trees was turning South Third Street into a utility pole graveyard.

Moore, who wasn’t nicknamed “Bully” for nothing, continued to chide the councilmen by distributing the following “anonymous” poem. (With apologies to Joyce Kilmer).

“I think that I shall never see,

A councilman who loves a tree.

Trees whose beauty add renown

To the fair name of our town.

For years they’ve stood through sun and rain

Yet for their life we plead in vain.

Well, only God can make a tree,

But councilmen are picked by fools like me.”

Resolute in posture and spirit, Louis T. Moore stands at Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington, one of his favorite tree-laden spots. Photo: Fales Collection, New Hanover County Public Library. |

Louis T. Moore turned 64 in 1949, a year in which he spent volunteer civic service hours learning what other cities were doing to address the problem of unnecessary tree removal. As a veteran researcher and freelance journalist, he had a wide network of contacts and soon discovered that Charleston had paid $3,300 to save the “Ashley Avenue Oak,” a 300-year old tree that would die of old age in about 1973. He also publicized the fact that New York City was going on the tree offense by encouraging tree plantings. Eight trees had recently been planted at Rockefeller Center and the idea captured Moore’s imagination. He later suggested that the Wilmington City Council begin celebrating an annual “Tree Planting Week,” and form a tree commission to “protect existing trees and to establish a program of ‘a tree planted for every one removed.’”

Moore continued his fight against what he called “horticultural murder” throughout his golden years, and his most dramatic battle occurred in 1950. Accompanied by friends who shared his love for the look of old Wilmington, Wallace Murchison, Burke H. Bridgers, and U. B. Ellis, Moore engaged in a two-hour battle with city council that became “hot and personal.” A large audience applauded loudly and long every time Moore scored a point for trees and they clapped like thunder when he accused the officials of “out-Stalining Stalin!”

Despite everyone’s efforts, 500 to 1,000 live oaks that ranged from mature to stately were ruthlessly felled from 1945 through 1950 along Third and Market streets in order to widen the roadbeds for increased traffic. Moore’s requests for the development of alternate routes were barely acknowledged. Rerouting commercial traffic alone could have saved the trees for another 30 years. “One is forced to speculate what other places in the U.S. would have permitted such wholesale demolition of trees,” wrote Moore to a local newspaper editor.

Then, in 1958, city government systematically destroyed an additional 600 trees following Hurricane Helene’s near miss on Sept. 26. Wind gusts up to 160 miles per hour and eight inches of rain had toppled many long-standing stalwarts, but the city manager subsequently ordered the demolition simply because he did not want to deal with downed utility lines in the event of another hurricane. “Many homes were without power of communication. It caused a tremendous inconvenience,” was virtually all the city manager could say in defense of his actions.

Louis Moore took this photo of the trees at Greenfield Lake in Wilmington. Photo: New Hanover County Library. |

Louis T. Moore’s last epic battle as a tree saver occurred in 1959. Grand live oaks that sat along Market Street north of downtown where the handsome Kenan Houses mark the entrance to Carolina Heights were in danger. The gracious two-lane street would eventually be compressed into the present four-lane road, but thanks to Moore and many others after him, at least some of the live oaks survived. Moore decried the plan and called for a city-ordained conservation program to protect existing trees and to establish a replanting program to make up for those already destroyed.

“The simple fact that New York City is now planting 1,800 trees along its principal avenues, costing approximately $100 each, furnishes a splendid example which Wilmington well could follow with a program of replacement,” he told the mayor and city council members. “This is in rather marked and decided contrast with the oft-repeated information seen in our local press: ‘Trees Will Be Removed.’ Trees are a God-given asset which require a century to mature, and which can be destroyed within a half hour when there is a plan to do so.”

Moore undoubtedly made a difference. The trees that remain on Third Street and along Market Street, stand in part because of his efforts. He raised awareness and caused a change in attitude toward preserving trees. By influencing the actions of those in power and of social prominence, Moore prevented further loss of these arboreal resources and secured their place of importance in the coastal city.

In addition to the actual trees, he saved images of them in many photographs. Some, like the World’s Largest Living Christmas Tree have survived, but look much different today. The Dram Tree, the trees of Greenfield, the Washington Oak, the Airlie Oak, the dogwoods at Oakdale Cemetery and many live oaks at Orton Plantation are just a few of the grand old trees he celebrated through photography. Moore also invited accomplished photographers like John Hemmer to visit Wilmington and take photos of our area to distribute in other parts of the state and to include in national magazine articles. Either way, Louis T. Moore was a preservationist before the word came into common use.

This article first appeared in the March 2009 issue of Wrightsville Beach Magazine.