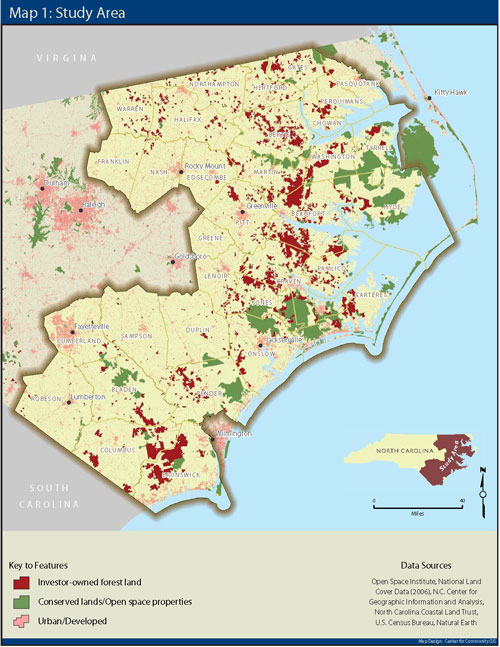

Thirty-three counties in Eastern North Carolina, from Brunswick to Pasquotank, make up one of 11 priority areas in the Southeast where there are innovative opportunities to preserve large tracts of “working forests” that could otherwise be developed, according to a study released Tuesday by a nonprofit land conservation organization.

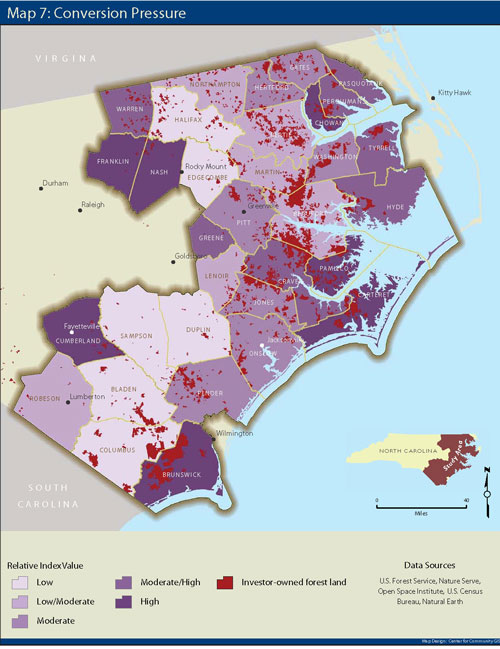

Although development has slowed since land prices peaked in 2006, the analysis by the Open Space Institute in New York suggests that as many as 344,000 acres of forestland along the coast —one of the world’s most productive for growing timber—could ultimately be converted to other uses, which would cost North Carolinians jobs while compromising water quality and wildlife habitat.

Supporter Spotlight

This analysis is drawn from Retaining Working Forests: Eastern North Carolina, an institute report released in collaboration with the Partnership for Southern Forest Conservation.

The institute protects scenic, natural and historic lands to ensure public enjoyment, conserve habitats and sustain community character. Through land acquisition and conservation easements, it has preserved 110,000 acres in New York State and has assisted in the protection of an additional 1.8 million acres, mostly in New England.

The partnership is a broad coalition of nonprofit groups and state and federal government agencies working to develop and promote innovative approaches to protect large forested tracts across the South.

“We hope the study shines the light on Eastern North Carolina because it contains critically important forestlands,” said Peter Howell, the institute’s executive vice president. “We want to inspire action by giving people good and comprehensive information to take those actions.”

North Carolina is currently the top forest-related employer in the Eastern United States. The industry, the study notes, employs nearly 80,000 people while contributing nearly $5 billion to North Carolina’s gross domestic product and generating $445 million in income taxes each year.

Supporter Spotlight

Coastal forests also bring irreplaceable public value by protecting clean water sources and wildlife habitat while buffering the state’s substantial investment in already-conserved public lands.

This combination of economic and ecological rewards is at the heart of the definition of a “working forest.” Such a forest stores carbon, filters water, controls floods, provides a home for plants and animals and offers a place to hunt, fish or take a leisurely walk in the woods. A working forest may also produce income for its owner by providing timber, pulpwood, herbs, wild edibles and medicines.

All that is obviously lost if the forest is cut down and replaced with a shopping mall or a housing development. The institute’s report raises that specter by outlining the economic realities facing the state’s forestland owners. That ownership has been in flux for more than a decade. The large timber and paper companies, which once owned vast tracts of Eastern North Carolina, have sold much of their holdings. The buyers in many instances have been entities called timber investment management organizations, or TIMOs, and real estate investment trusts, or REITs. They manage large tracts of forestland for investors.

Because of the size of their holdings, these investment groups, the study notes, are both critical conservation partners and important contributors to local economies. The average size of forestland ownership in North Carolina is less than 15 acres, the study reports, but the seven TIMOs and REITs with forestland in the region hold an average of 153,000 acres.

Because of the size of their holdings, these investment groups, the study notes, are both critical conservation partners and important contributors to local economies. The average size of forestland ownership in North Carolina is less than 15 acres, the study reports, but the seven TIMOs and REITs with forestland in the region hold an average of 153,000 acres.

These investment groups bought much of the land at the height of the market, Howell said. They’re fragile and may be underwater, he said

These REITS and TIMOs are really different than industrial forest owners,” Howell said. “Unlike the industrials which were really only, or mostly about timbering, these new entities are committed to doing whatever they can to achieve the highest possible return, whether it be timber harvesting or development. In some ways, they’re focused much more on the bottom line.”

Forestland in Eastern North Carolina plays a critical role in maintaining rural drinking water quality. The conversion of these forests to other uses would increase sediment and nitrogen loading within estuaries, degrading household and municipal water sources for some 4 million people, the report says.

The eastern part of the state also boasts the richest coastal biodiversity in the United States outside of Florida. The region supports endangered wildlife habitat, with as many as 83 at-risk species per county, including the red-cockaded woodpecker, Bachman’s sparrow, red wolf, Carolina crawfish frog and mimic glass lizard.

Those benefits, which are detailed in the report, along with the eastern forest’s economic return to landowners got Steven Troxler’s attention. He is the state’s commissioner of Agriculture and his department contains the state’s forestry division.

“I highly encourage giving careful consideration to this report,” he said. “We must make thoughtful decisions to ensure that North Carolinians continue to reap the benefits of our working forests.”

But only 2 percent of the state’s working forests are protected with conservation easements—one of the primary tools that landowners, nonprofits and government agencies have used in other parts of the country to preserve working forests.

Much of the money for those easements came from the federal Forest Legacy Program under the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Since its inception in 1990, the program has paid for easements that have protected more 2 million acres in 43 states and territories, but less than 5,000 of those acres are in North Carolina. Easements allow owners to continue to own the land and harvest the trees, but prevent the land from being developed

The report also evaluates other conservation tools, such as Department of Defense programs, wetland mitigation, endangered species banking and longleaf pine restoration credits.

As the lasting implications of the 2008 economic downturn become clear, the study emphasizes that nonprofits, landowners and policymakers must work together to identify ways to keep forestland as forest.

The study offers some new strategies to do that, noted Camilla Herlevich, the executive director of the N.C. Coastal Land Trust in Wilmington. “It’s always good to highlight the tools that are out there, especially right now when state funding is on the skids,” she said.

After several years of budget cuts to the state conservation funds normally used to protect forests, landowners and conservation groups need to become creative in fashioning projects, she said. Those timber investor groups, for instance, could be attracted to deals that provide ways to make money from a forested tract’s recreational or habitat values, Herlevich said.

“These timberland investors are not any different than the timber companies because they are looking for returns,” she said. “The investment groups may be more nimble and more open to other ways to make that return.”

That kind of creative thinking is needed, said Kim Elliman, the institute’s CEO and president. “We are at a critical juncture and must identify new markets and strategic incentives for retaining large working forests,” she said. “In this report, we state the challenge and find some new opportunities for achieving conservation at scale.”