Last of two parts

Just when you thought it was safe to play in the swamp, along comes news about the state’s new mercury study that reminds you that something’s happening out there that we need to think about and work to correct.

Supporter Spotlight

I’ve spent much of my life exploring swamps and other aquatic realms and in that time I have come to know a great many interesting plants and animals. While alligators, eagles and other so-called “glamorous megafauna” grab headlines and dominate conservation efforts, I have long been attracted to the smaller beings in the world we share. Tiny crustaceans including dot-sized copepods, daphnia and even mosquito larvae are the things I seek, before I start looking for fishes, frogs, turtles or birds.

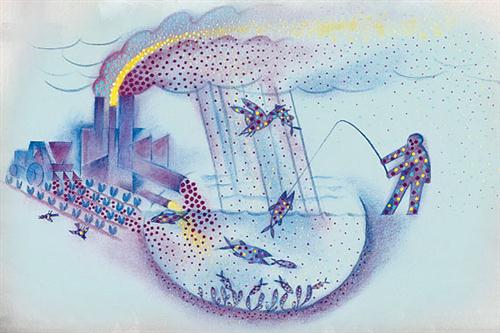

Credit: Frédéric Back and Québec Amérique |

I could be equally charmed by protozoans and bacteria, since they inhabit every sample of pond water I examine, but the hand lens I carry can’t discern these tiniest of beings. Bacteria inhabit every ecosystem we have examined, and even though daily life functions require a diverse collection of bacteria inhabiting our body, these “animalcules” as they were first called, are rarely celebrated.

Bacterial activity drives entire ecosystems. Some kinds break down carbon compounds – the remains of once-living organisms– while others are chemical converters, nitrogen cycling for example. Some bacteria cycle chemicals as a metabolic activity required to expel wastes from their cell structure. As an example of this is found in coastal areas, where hydrogen sulfide, a waste product of sulfate-reducing bacteria, can be smelled when carbon-based organic sediments are exposed during low tide. The rotten egg smell is essentially the exhalations of marsh bacteria reducing carbon compounds.

While sulfate bacteria are processing organic compounds in sediments they may also bind up various chemicals, including mercury deposited from the atmosphere. The bacteria don’t necessarily seek out mercury, they simply encounter it. To rid themselves of this unneeded material, bacteria employ metabolic processing to convert the mercury to methylmercury, a chemical compound that bacteria can expel.

Mercury is a naturally-occurring element in the environment, though rarely in high concentrations. The mercury in thermometers and electronic switches is a highly refined product extracted from mercury-containing ores. While elemental mercury is a hazardous material, a more nuanced form, known as methylmercury (CH3Hg), is far more insidious, hazardous, and unfortunately, inside each member of every community across the globe.

Supporter Spotlight

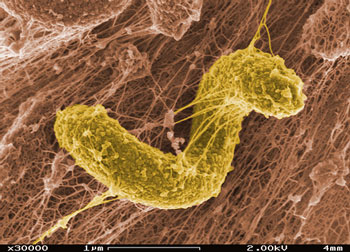

At the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory of the U.S. Energy Dept., scientists investigate biofilms of the sulfate-reducing, anaerobic bacteria Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. This microorganism is being studied for its ability to reduce toxic metals and radionuclides such as chromium and uranium in soils and groundwater. The photo is a color-enhanced digital micrograph of a black and white scanning electron microscope image. Thanks to Alice Dohnalkova for the image. |

Mercury can be found wafting through the atmosphere attached to a water droplet, or adhered to a dust particle. Atmospheric mercury can originate from a volcano, but since we can’t do much about volcanoes, we focus on the mercury pollution generated by burning coal, manufacturing cement from limestone, incinerating medical and other wastes and processing various metals. Atmospheric mercury released from industrial smokestacks may stay aloft for thousands of miles before falling to earth, most likely landing in water.

In its elemental state mercury is unhealthy to higher forms of life, but methylmercury is even more insidious and harmful. Animals exposed to methylmercury, especially during early development stages, may suffer severe neurological damage and other health problems that inhibit full function and vigor. Adult animals are also at risk from methylmercury and none more than aquatic predators high up the food chain.

In the 1980s largemouth bass in North Carolina were included in a mercury advisory that warned people to limit consumption of this fish. The reason for the warning, still in place today, has everything to do with a process called biomagnification. Biomagnification refers to a natural concentration of compounds especially in the tissues of animals that are part of a complex food pyramid.

Picture a pyramid divided by horizontal layers, with each layer representing a step in a food chain. At the bottom of the pyramid we find primary producers known as plants. In the layer above plants are plant eaters. The next layers up are eaters of plant eaters and above them are eaters of eaters of plant eaters, and so-on to the top of the food pyramid; represented in this example by largemouth bass.

Mercury originating from coal combustion is deposited in sediments supporting the base of the food pyramid. Sulfate-reducing bacteria exposed to mercury convert it to methylmercury in order to rid themselves of the metal. Because it accumulates in muscle tissue in the “eat and be eaten” food pyramid, methylmercury is transferred from one organism to the next, magnifying with each level climbed. In this way methylmercury adhered to tiny copepods, daphnia and even mosquito larvae is passed to small fishes including mosquitofish and young sunfish. These in turn are eaten by slightly larger fishes that in their turn are eaten by still bigger fishes including bass, catfish, bowfin and others. This chain of events involving other players is also happening in the world’s ocean; hence the mercury advisories for tuna, swordfish and other so-called apex predators.

|

The study of methylmercury and its “lifecycle” is interesting and fraught with alarming revelations too important to ignore. So too is the study of the politics involved in regulating the discharge of mercury, the precursor to methylmercury.

When I hear complaints from industry members about the harm regulations put on their business, I am reminded of something a chemical plant manager shared with me many years ago. He said the chemical industry thrives best when it sees pollution as wasted product, and missed profit. In short, environmental protections are conservative measures that support best business practices. And when businesses behave well, communities thrive. It does not work the other way around.

Conservation educators often position a glamorous wild predator to illustrate the apex animal in a food pyramid, be it a shark, lion or bear. In truth, the top of the pyramid is reserved for but one species, and it is us. For this reason, it is in the interest of everyone that we put aside distracting arguments about economic well being and focus instead on the health of the ecosystems that support our economy.