A federal proposal to designate portions of coastal rivers in North Carolina as habitat essential to the survival of the endangered Atlantic sturgeon will not add another layer of regulations for fishermen, boaters, dredgers and others using those rivers, federal officials say.

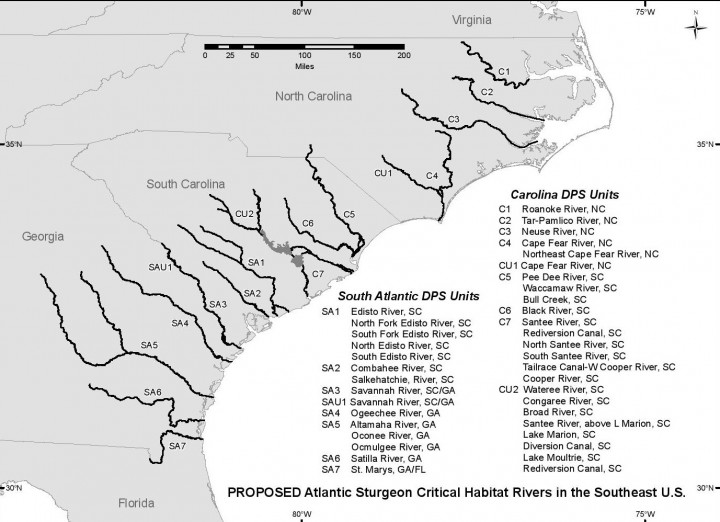

Officials with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released a proposal earlier this month to designate critical habitats for sturgeon in coastal rivers along the East Coast. About 915 miles of waterways in the Yadkin-Pee Dee, Waccamaw, Cape Fear, Northeast Cape Fear, Black, Neuse, Tar-Pamlico and Roanoke rivers in North Carolina are included in the designation.

Required by the federal Endangered Species Act, the designation is meant to protect spawning, foraging and other areas that are important to the survival of the fish. The sturgeon was listed as endangered in 2012.

Supporter Spotlight

A public hearing on the proposal will be held 7 p.m. Thursday at the Crystal Coast Civic Center in Morehead City. It will be the only hearing in North Carolina. Comments on the proposal can be submitted to NOAA until Sept. 1.

Sturgeon, a large bony fish known for its roe used for caviar, are called anadromous fish because they spawn upriver in fresh water but spend most of their lives in marine or estuary waters. The species dates back 120 million years to the time of the dinosaurs. In the 1800s, Atlantic waters teemed with the fish, which can span 15 feet and weigh 800 pounds. However, in the last century, numbers have fallen drastically due to overfishing, and sturgeon fishing was banned in North Carolina more than 20 years ago in an attempt to recoup the numbers.

Designated Locations

Areas were designated based on their importance to the species’ recovery. As stated in the proposal, Atlantic sturgeon spawn and spend their early life in rivers, making the habitats vital to the success of the species.

“An essential feature for Atlantic sturgeon spawning is unobstructed migratory pathways for safe movement of adults to and from upstream spawning areas as well as providing safe movement for the larvae and juveniles moving downstream,” the proposal says.

The proposal states that after analysis, the following features were found to be essential for the conservation of the Atlantic sturgeon: hard bottom, transitional salinity zones, appropriate depth and physical barriers and appropriate water quality conditions.

NOAA officials said these critical areas are important because even when the fish is migrating, its habitat can still be protected.

“It’s important because we can designate these areas even if the animal is not around,” said Andy Herndon, Atlantic sturgeon and shortnose sturgeon coordinator at NOAA.

Although the critical habitat designation was supposed to be proposed within a year after the fish was listed, it was not until a lawsuit filed by the Delaware Riverkeeper Alliance and the Natural Resources Defense Council that NOAA took action this year. Lawsuits – or the threat of them — normally spur the federal government to designate critical habitat.

Federal Oversight

Currently, because of the species’ endangered status, federal actions must be regulated to prevent harm to the fish. According to NOAA officials, this additional designation means if a federal action or permit is up for approval, the effects to the sturgeon’s critical habitats must also be assessed by NOAA, the agency that manages endangered fish.

“When federal agencies conduct or authorize an action that might have an impact on the Atlantic sturgeon critical habitat they’re required to, what we call, consult with us on that,” said Herndon.

Herndon said the designation proposal would not be another layer of regulation, but another consideration when approving projects.

During the consultation, according to the proposal, NOAA will ensure that the proposed actions “are not likely to destroy or adversely modify critical habitat.”

In a draft assessment report, NOAA highlighted 14 federal activities in the designated areas that may require consultation. Activities include dredging and coastal engineering, nuclear power plant construction and fishery management. Any federal loans or permits related to these activities may be affected by the designations as well.

In the assessment report, NOAA estimates that 205 projects will require consultation during the next 10 years because of the critical habitat designation, with a projected administrative cost of about $1 million.

Research is underway at Virginia Commonwealth University to uncover the secrets of a charismatic, endangered species, the Atlantic sturgeon. This short documentary follows Matt Balazik as he discovers, for the first time, the sturgeon migration using acoustic transmitter tags.

Fishing and Dredging

Most of the concerns on the coast center around fishing and dredging.

Jason Rueter, NOAA’s Gulf sturgeon coordinator, said by email that commercial fishing will likely not be affected by the sturgeon habitat designation, but that dredging may be.

Greg “Rudi” Rudolph, Carteret County’s shore protection manager, said while he is glad the critical habitat areas are in rivers and not on the oceanfront, he still worries about the effect the proposal will have on dredging.

According to Rudolph, Atlantic sturgeon use inlets to get from freshwater rivers to the ocean, where they live most of their adult life. Rudolph said inlets are also important for beach dredging and that designations like these may make dredging more difficult.

“Even if the critical habitat technically doesn’t do anything in terms of a hardcore regulation,” he said, “it does intensify what things we may have to do to avoid harming a species.”

Fred Harris, an aquatic resource specialist with the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, said that in NOAA’s consultation, the sturgeon’s seasonal usage of the inlets would likely be considered. That way, he said, alternative times for dredging activities can be considered. He added that the designation would likely not stop activities, but rather force people to rethink them.

“Identifying this critical habitat doesn’t necessarily mean none of those projects are going to happen,” he said, “it’s just they look at them carefully, and they look for all alternatives that would be less damaging to the animal’s habitat.”