BEAUFORT — The video feed begins at ground level with close-ups of a few blades of grass. Soon, though, the tiny aircraft soars overhead and offers up majestic views of marshes and river. Or, in other cases, beaches and forests, or the community clubhouse and pool. Similar scenic, aerial videos of locations around the world, set to soothing music, can be found on YouTube and on Facebook feeds.

These unmanned aerial vehicles, more commonly known as drones and less commonly as UAVs, have transitioned from a strictly military use to the world of hobbyists, cinematographers and entrepreneurs. Local scientists, too, see the possibilities of UAVs.

Supporter Spotlight

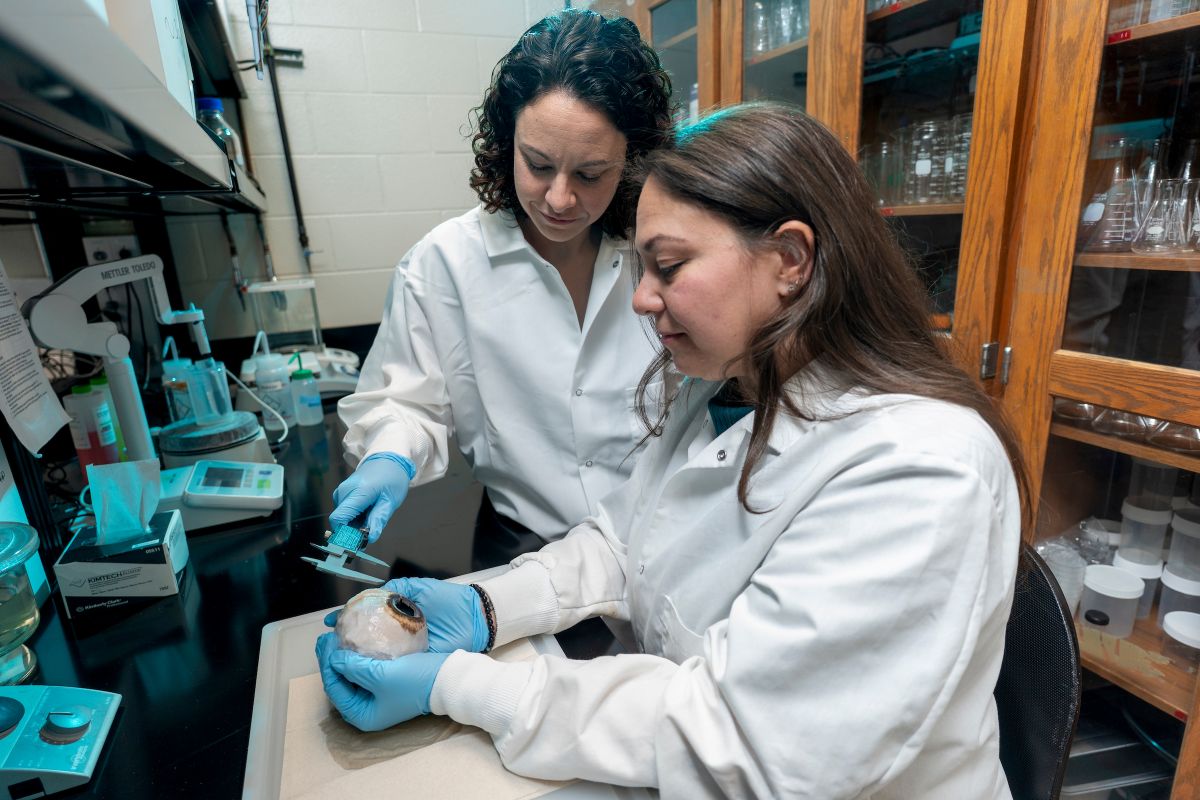

Larisa Avens, a research fishery biologist, has been working to estimate sea turtle populations along the N.C. coast since 2007. She plans to use drones next spring, when sea turtles congregate at Cape Lookout National Seashore, as part of a population study for NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center in Beaufort. Previous work used satellite data and on-the-water collection techniques to estimate the number, health and turtle species.

“We’ve looked at manned aerial efforts, too,” she said. “But they are expensive, and can be challenging logistically to schedule a crew and plane. They are also potentially dangerous.”

Drones, though, are less expensive and more responsive. Previous work has shown kind of a migratory bottleneck at Cape Lookout, of mostly loggerhead turtles. “But we’ve also seen some Kemp’s Ridley,” she said.

There is still much to be learned about this smallest of sea turtles and the promise of drones could fill in gaps, Avens noted.

Gary Roberson, a biological and agricultural engineering professor at N.C. State University, already knows the benefits of drones in agriculture. “With UAV, there’s an opportunity for farmers to really know and understand what’s going on out in the field,” he said.

Supporter Spotlight

It’s a way to look at everything from nitrogen content in corn fields to disease detection in peanut crops, Roberson added.

And Sara Schweitzer, a wildlife diversity biologist with N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, hopes to use drones to gather more information about the nesting sites of marine birds like brown pelicans and snowy egrets, especially in remote areas “A lot of the groundwork we do is disruptive,” she said. “But with this, we can get to areas most people can’t.”

The possibilities don’t end there. Theoretically, drones can be used to evaluate the condition of coastal infrastructure, such as lighthouses, study shoreline erosion or calculate the amount of debris in the ocean. They could be used in emergency situations, to help stranded wildlife or to measure the effects of sea-level rise.

“It’s not just about pretty pictures,” Roberson said. “There are layers and layers of data that can be analyzed here.”

The Federal Aviation Administration is scheduled to clarify a plan for the safe use of civil unmanned aircraft systems in the next year. Until then, special permits and exemptions must be granted on a case by case basis. Avens is currently working to finalize four layers of permits before she can proceed with the springtime project. In addition to the FAA, the group needs to negotiate with officials about using military airspace, as well as the park service land the site encompasses. She also is obtaining the necessary authorization for research that can affect endangered species. “There are a lot of stakeholders in this process,” she said.

The excitement about working with drones has not caught up to the regulatory end of the process. “I understand their caution,” Roberson said. “There are a lot of very real concerns.”

Those fears range from aviators worried about encountering drones on their flight paths to issues of privacy and inappropriate use. “It’s the same with any new technology,” he said.

Unmanned aircraft have been around for a while, but recent advances in drone equipment, sensors, software, GPS systems and cameras have created an ideal confluence for experimenting with what new UAVs can do. A quick stop to an online marketplace reveals how accessible drones can be, with models available under $100.

UAVs that can navigate difficult marine environments are more expensive, but still feasible for research purposes. A bigger price tag comes with the software. “We need very explicit software programming,” Avens said.

First, there is software that will pilot the drone in uniform patterns. “It needs to stay on track and cover a very specific area,” she said. There is also a need for software that can help analyze the data it collects.

Avens’ work is part of a larger network of research to be undertaken by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said J.C. Coffey, a lead systems engineer for the organization’s unmanned aircraft system project. “NOAA and its partners believe UAVs and other unmanned systems have the potential to efficiently and safely bridge critical observation gaps in hard-to-reach regions of the Earth, such as the Arctic and remote ocean areas,” he said.

In North Carolina, the group is working with scientists for surveys of menhaden and sea grass, as well as work in the National Estuarine Research Reserve.

The Raleigh-based Precision Hawk already knows the value of drone data. The company, founded in 2008, now has a global presence, often working more in Latin America and Canada than in the United States. In many cases stateside, the company files for an exemption and are allowed to operate the UAVs they manufacture and help clients understand the information.

“Once the rules are more firmly in place, we foresee agriculture making up about 80 percent of the market,” said Lia Reich, senior director of communications for the company.

Insurance companies could also be major customers, she said. “Following a hurricane, for example, claims agents can be equipped with UAVs and be able to assess the damage right there,” Reich noted.

Recently, David Johnston, an assistant professor at Duke University Marine Laboratory near Beaufort, hosted a workshop for 55 attendees on using UAVs in marine science. Plans were also announced plans earlier this month for a facility at the lab that can help fills the gaps in training UAV pilots and hardware support for scientists seeking to use drones in their work.

“It’s a great chance to collaborate for analytic use of UAVs,” Schweitzer said.

Already, the Duke program will be supporting a research effort in Costa Rica this fall to study seal populations. They also have an outreach program in the works with East Carteret High School in Beaufort. The N.C. Coastal Federation will allow Duke researchers to use drones to monitor wetlands restoration at its sprawling North River Farms project in eastern Carteret County.

At NCSU, the mechanical engineering department has been building drones for 30 years, Roberson said. Now, a collaboration course is planned for the fall, in which students will first build a drone and then learn more about how to use it in research. “It’s a start to finish project, where on the back end we will be focusing on data,” he said.

“There’s a lot of excitement right now,” Roberson said. Although interest in any new tools waxes and wanes, he thinks the potential of UAVs will stand the test of time. “Once we know more about real world applications, it will build again,” he noted.