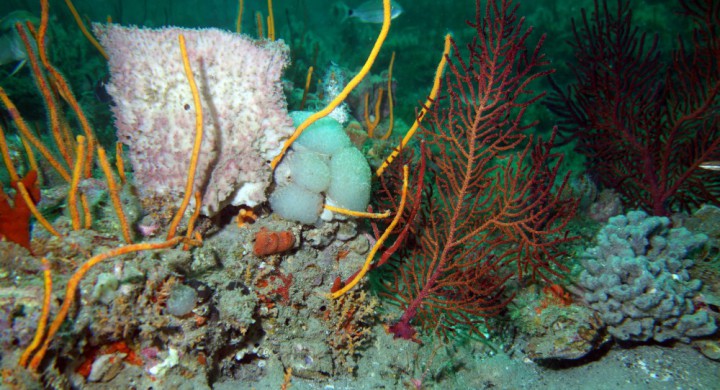

MOREHEAD CITY — Only the repetitive release of air from her regulator breaks the sea’s silence as a school passes her in a silver current. Avery Paxton counts the fish by the hundreds. She is drifting buoyantly above a jagged, narrow ridge, which her team of divers has named Lightning Bolt Ledge, admiring how the black sea bass and tautog forage near the reef just as the angelfish do.

The “little islands of marine life out in the middle of the sandy desert,” as she calls the offshore reefs that she studies, are as close as 1.7 nautical miles from shore and as far as 43.

Sponsor Spotlight

Scientific diver, Alyssa Adler, measures the topography of a hard-bottom reef off North Carolina. Studying the structural features and ecology of the reefs will help with their conservation. Photo credit: Avery Paxton/UNC Institute of Marine Sciences |

Lightning Bolt Ledge is 26 nautical miles away from Wilmington, in one of the windiest areas off the East Coast. One that the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, will potentially lease for the development of wind farms.

Avery Paxton |

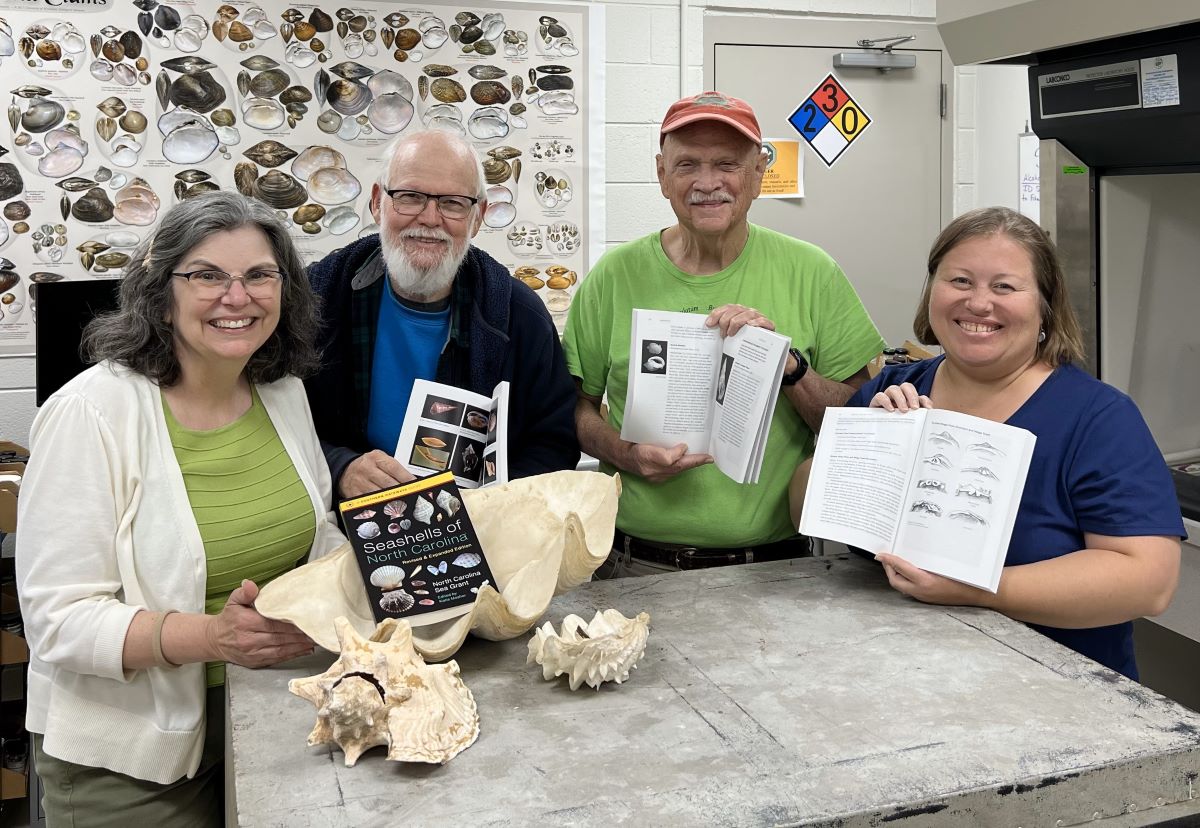

Paxton, 25, is a graduate student at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’sInstitute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City. Her research is funded in part by BOEM to identify the most important fish habitats within one of the three areas off the N.C. coast that the agency has designated for possible wind turbines. This one, known as Wilmington-East, is roughly 134,000 square miles of ocean just southeast of Wilmington’s port.

She is studying how fish selectively use the different types of hard-bottom reefs. Fish use the reefs for feeding, some for spawning or as nurseries. Others swim from reef to reef seeking refuge, said Paxton, to move safely to deeper water. They’re important resources for the fishing industry and ecotourism, too. By understanding which reef habitats are essential to conserve, developers can make informed decisions about where to build their wind turbines, Paxton explained.

Amid the blue-tinted world, Paxton’s GoPro camera films yellow, tropical butterflyfish fluttering past a tall sea sponge while she jots down notes on her slate. “I think one of the most interesting things to me as a scientist and a diver is that we have a mix of these colder-water species and these warmer-water species,” Paxton said.

The warm Gulf Stream mixes with colder, nutrient-rich water as it flows north past Cape Hatteras. The mixing creates a diverse array of marine life, including plants like seaweed, called macro-algae by scientists.

Sponsor Spotlight

“They’re not a simple system,” said Paxton. “There are so many species. Just macro-algae, for example, there’s over 90 species, and one of the really cool things is that these macro-algae, they’re seasonal. So it’s kind of like the trees that we have, right, they bloom during one season, the leaves fall off, they bloom again — the same thing happens underwater.”

The reefs are as diverse as the marine life. Half of them are made of rock or different kinds of sediment cemented together. The other half are artificial: shipwrecks or manmade boxcars and concrete pipes. Some, like the ribs of a sunken ship, stick 30 feet out into the water column. Other “features,” as the scientists like to call them, are flat as a stage. And sometimes the reefs are ephemeral, temporarily buried by sand until a storm exposes them again.

| Research divers with UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences use GoPro cameras to capture the abundant life on this natural hard-bottom reef off North Carolina’s coast. Video: Avery Paxton/UNC Institute of Marine Sciences |

There were several studies on the ecology of offshore reefs in the 1970s, ‘80s and some in the ‘90s, but since then there really hasn’t been too much additional work, said Paxton. “And there’s still a lot of unanswered questions.”

She studies 32 hard-bottom reefs seasonally – 16 within and outside of Wilmington-East funded by the federal agency and 16 closer to Cape Lookout using grant money from the state’s recreational saltwater fishing license.

“By not sticking with one set of reefs, one distance and depth offshore, but rather looking at a whole package of reefs, different types, several depths and distances offshore, [we’re seeking] to set a baseline of information,” said Charles “Pete” Peterson, a professor at UNC and one of the study’s principal investigators.

“So that as we develop wind power offshore we can see how changes occur; and as climate changes as well, we see how changes occur independent of any wind power influence,” said Peterson. “This could be Avery’s career.”

Her research is not only important to offshore wind energy development, but in sketching the big picture of North Carolina’s offshore reefs in all their shades and colors.

“I’ve been most impressed by the fact that we have these amazing reefs off the coast of North Carolina,” said Paxton. “[Many people] know about shipwrecks because the Battle of the Atlantic happened here and it’s the Graveyard of the Atlantic, but not many people realize that we have these reefs that are similar to tropical reefs right in our backyard.”