Annie Harshbarger had been interested in animal behavior ever since she was young. Now, as a doctoral candidate at Duke University’s Marine Lab, she is currently building her thesis on decision-making in pilot whale social groups.

“I sort of knew when I started college that I wanted to study the behavior of whales and dolphins,” Harshbarger said. “The way that they navigate this really challenging environment that they’ve evolved to live in is very interesting.”

Supporter Spotlight

Harshbarger spoke about the way we can see this in the behaviors of whales off the coast of Cape Hatteras. She said in a talk at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences that the behavior of pilot whales in that area demonstrates this flexibility. “They’re generalist foragers, so they can eat a lot of different things, so that means they can live in a lot of different habitats, and their behavior varies with what they live and what they’re eating.”

Pilot whales’ flexibility is tempered by the needs of their social groups, however. Unlike other whale species, they stay with the same group of whales for their entire lives (with occasional exceptions of males who join other groups to mate). When pilot whales dive for food, they do so together. Harshbarger is studying how those groups make decisions at different points throughout this process — a question without a lot of known answers, as of now.

New technology brings new information

One of the tools Harshbarger is using for her thesis is data gathered from digital acoustic recording tags, or DTAGs. These tracking tags can capture whale movement in three dimensions, painting a much more holistic picture of their behavior, and as the name implies, they record sound as well as movement. The technology was initially developed in 2003 by Mark Johnson and Peter Tyack in order to better understand the ways in which human-made noise pollution potentially affects the behavior of whales and dolphins.

“They were designed to study the effects of anthropogenic noise. We didn’t have the tools to understand the ways that noise pollution affects marine life. Peter and Mark came up with the tags to tackle that,” said Dr. Andy Read, director of the Duke Marine Lab and Harshbarger’s academic adviser.

Now this technology is being used to paint a fuller picture of what pilot whales are doing beneath the ocean’s surface. Harshbarger explained that the acoustic tags not only captured sound, but depth and movement in three dimensions. This allows researchers to study specific details about the whales’ diving behavior. Harshbarger is particularly interested in this data because of her focus on how pilot whales decide as a group when and where to look for food.

Supporter Spotlight

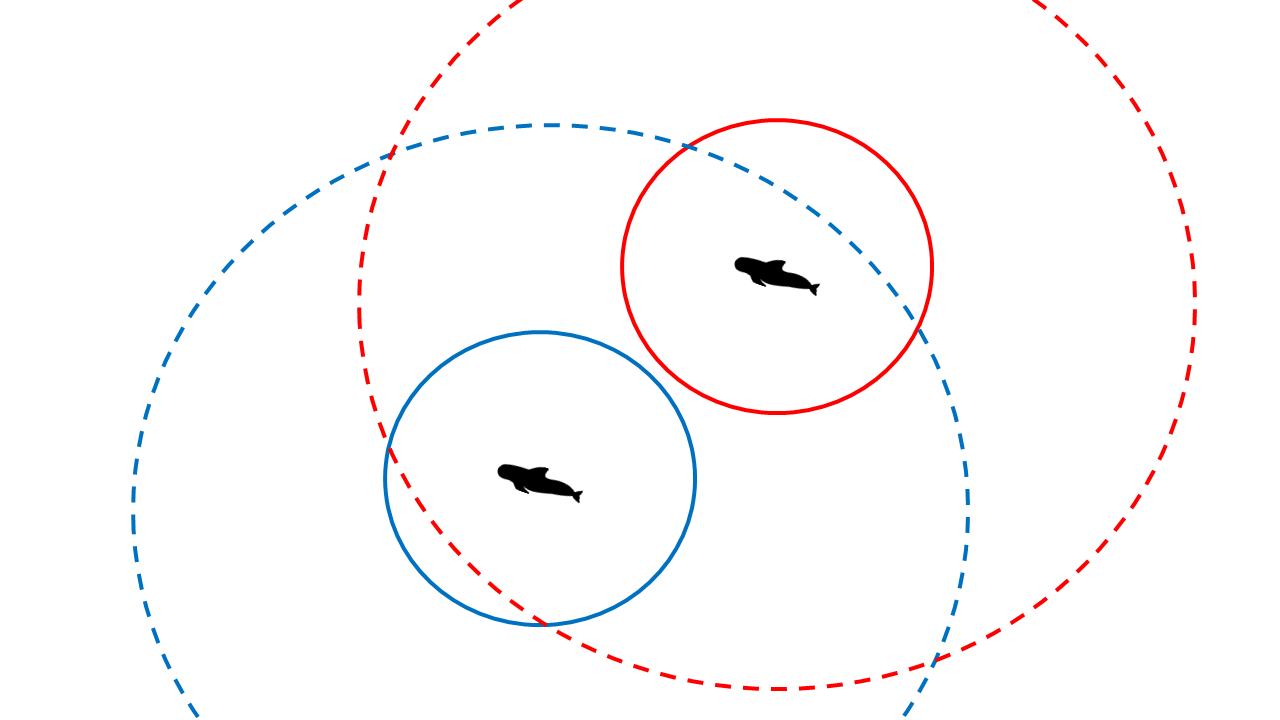

The information shows that pilot whales usually stick together throughout the entirety of their dives. It was originally hypothesized that while hunting, pilot whales would stay far enough apart from one another so as to avoid competition while also staying close enough that they could still hear each other.

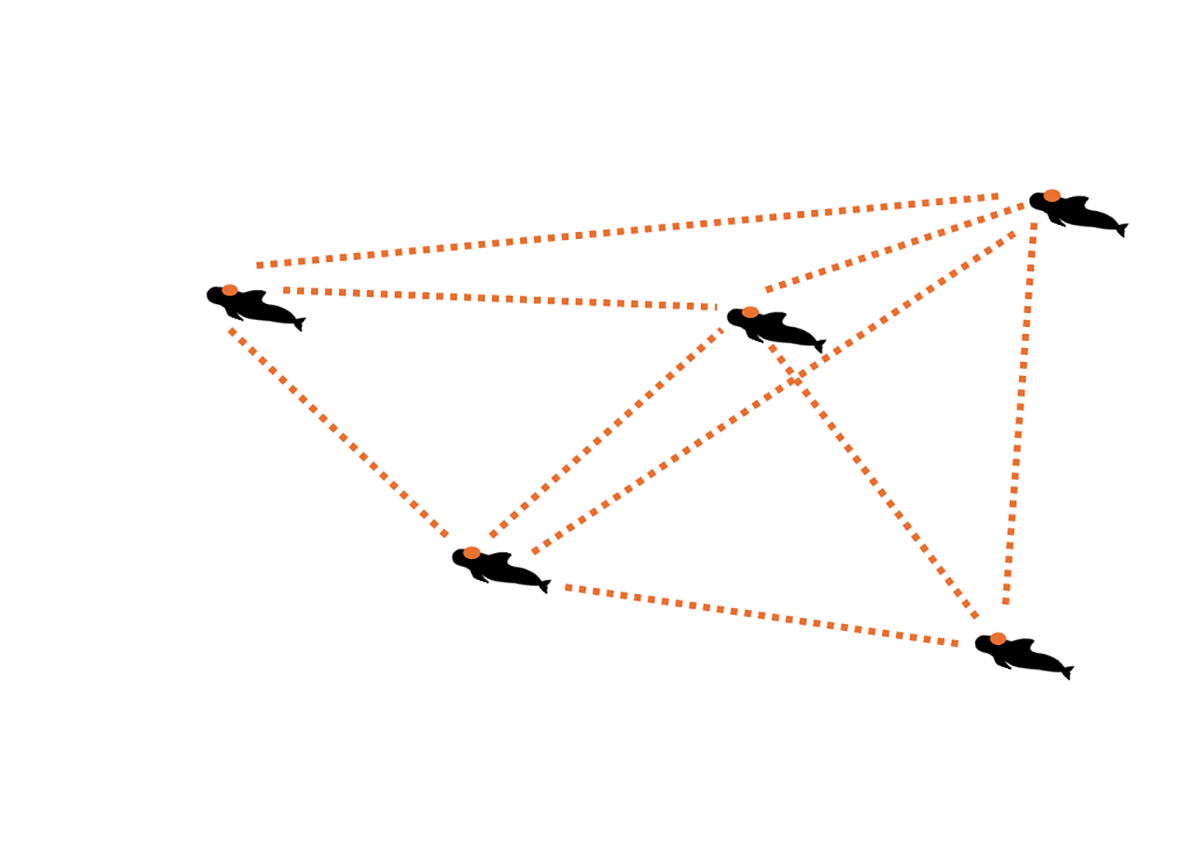

To test this, researchers used information gathered from the acoustic tags. Because the tags have special hydrophones attached, they are able to record the sounds in such a way that they can gain an approximation of each whale’s position relative to the others.

“We can really understand how the group is foraging separately and together like we never have before,” Harshbarger said.

Tackling the big questions

One of the great unknowns with pilot whale behavior has to do with their decision-making processes. They are flexible animals who eat a wide variety of food found in many different environments. So how do they decide when and where to eat? Because pilot whale populations around the world are so large and varied, it can be difficult to track any one group consistently enough to determine the specifics of their behavior.

This is the question that Harshbarger is trying to help answer. “I found that decision-making process really interesting. So I’m studying how groups of pilot whales make decisions at different points in the dive cycle,” she said. Harshbarger compared it to a large family or group of friends trying to decide where to go for dinner. There are a number of options, and it can be difficult to make a decision for a big group of people. The same rule applies to pilot whales.

Harshbarger hopes that her research will begin to tackle these questions. Data gathered from the tagging of the Gibraltar whales has already answered some of them. By examining the audio and movement information gathered from the acoustic tags, researchers have learned that pilot whales not only dive together, but they usually forage for food at the same depths as well, even though there isn’t currently any evidence of them sharing prey.

The question of how pilot whales make decisions as a group remains mostly unanswered. Large populations and limited technology makes tracking them difficult in the long term. Acoustic tags stay on the whales’ bodies for around 24 hours maximum, so information is still limited.

“I think Annie’s work is probably going to leave us with a lot more questions. The potential conflicts between animals in groups is a really interesting idea. But Annie’s going to address the first, fundamental questions,” Read said.

Harshbarger said she believes in the value of studying and understanding these whales’ habits and behaviors, even if they are not currently endangered. There have been instances where local populations have suffered declines due to disease, and those populations’ behaviors changed as a result. Researchers were only able to notice that change because they had been observing the population beforehand.

“I think that’s kind of why I’m really interested in this, even for pilot whales, which are not necessarily something that people think of as the species with the most pressing conservation needs,” Harshbarger said. “That’s why I think it’s valuable to understand social behavior in any species, because you know that could change for them at any time.”