“We have had nine 100-year storms in the last 20 years,” said Dr. Reide Corbett during a conference in Wilmington back in November. “Somebody said that math doesn’t math.”

Corbett is dean of the East Carolina University Coastal Studies Institute Campus in Wanchese and he was addressing the fourth annual Water Adaptations to Ensure Regional Success, or WATERS, Summit held Nov. 13. He said the statistical model used to predict precipitation frequency is no longer reliable.

Supporter Spotlight

The model, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Atlas 14 data server, is widely used in infrastructure planning and flood risk assessments. Atlas 14 provides statistical modeling that is based on rainfall amounts and storm intensity for the 30 years leading up to the 21st century.

The server “contains precipitation frequency estimates for the United States and U.S. affiliated territories,” according to NOAA.

Corbett told those attending the summit that Atlas 14 “doesn’t hold any longer.”

In a follow-up interview with Coastal Review, Corbett said the problem with Atlas 14 is that it does not factor in how the climate has changed during this century.

“It does not take into account changes in the moisture that the atmosphere has, and it certainly doesn’t project forward,” Corbett said.

Supporter Spotlight

That’s why NOAA is developing an Atlas 15 model, which is to be rolled out in stages this year and 2027. When completed, “Atlas 15 will supersede NOAA Atlas 14 as the national standard and will become the authoritative source for precipitation frequency information across the United States.,” according to the NOAA website.

Dr. Jared Bowden, interim director of the North Carolina State Climate Office, agreed that, as a predictive model, Atlas 14 is flawed.

“It doesn’t use the most recent observations. (Atlas 14) hasn’t used any of the data in the past 20 or 25, years, really,” Bowden said.

Atlas 15 is expected to correct that shortcoming nationally, but in the meantime, the State Climate Office has developed a dataset that illustrates how precipitation patterns represented in Atlas 14 may evolve over time.

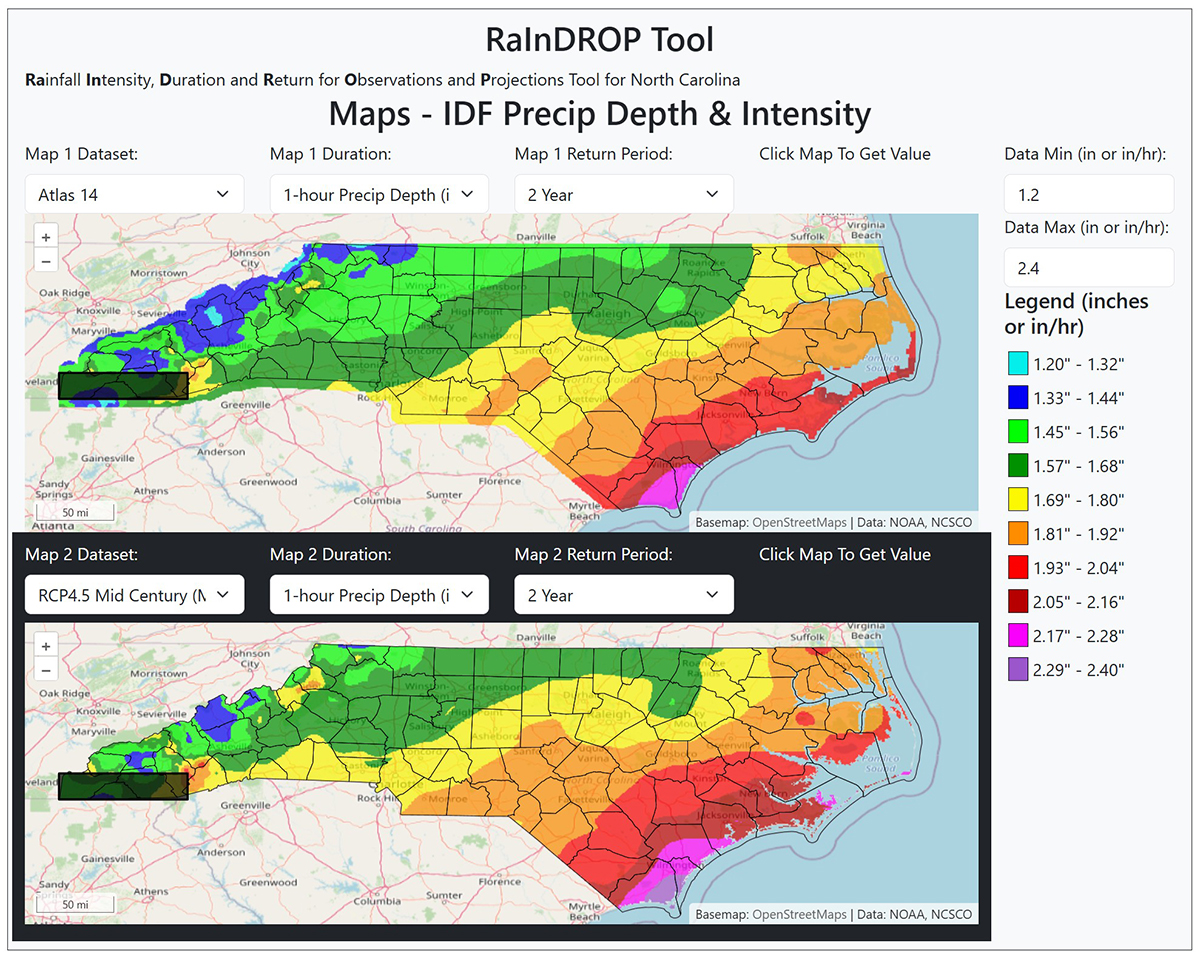

RaInDROP, an acronym for the statistical information for the state model, Rainfall, Intensity, Duration and Return for Observations and Projections, is “a product that is tailored to North Carolina,” Bowden said. “Some things in the methodology that we do behind RaInDROP are very North Carolina specific.”

The datasets the State Climate Office developed use the Atlas 14 model as a baseline, but also predict what the future climate will look like. The modeling also takes into account North Carolina’s geography, Bowden said.

“There’s eight climate divisions across our state, and we use these climate divisions to help think about how we scale Atlas 14 values,” Bowden said. “We took climate change projections and tried to figure out how you would scale up based on the different climate divisions.”

The online RaInDROP tool maps show marked variations from Atlas 14 data. For instance, the southeast corner of the state, New Bern, Jacksonville and Wilmington, in particular, will experience significantly more rainfall and more intense events than previously modeled. Bordering the Atlantic Ocean, that output is consistent with climate change data that shows a warming atmosphere.

Climate change is not a linear increase with temperature and moisture, Bowden explained. Rather it’s an exponential increase and an exponential increase in moisture capacity.

“If you’re able to saturate the atmosphere and have a forcing mechanism to wring it out of the atmosphere, such as a hurricane, then you get these really big downpours. You get these really big flooding scenarios that will create just larger and larger problems for our infrastructure.”

The climate office tool is designed to have practical applications in designing infrastructure.

“If you’re looking out at midcentury, let’s say 2050- or 2060-time frame, and you were to design a culvert that’s supposed to last that period of time, how would your design criteria change based on using plausible future scenarios?” Bowden continued.

Public and private infrastructure rely upon reasonably accurate climate models to determine design criteria. Retention ponds, as an example, typically use a 4% annual chance of a 25-year storm as design criteria. Based on that assumption, a retention pond should perform as expected provided the storm events occur as predicted by Atlas 14.

However, climate events predicted by RaInDROP suggest that what is now thought of as a 25-year storm will be more frequent and more intense, and if that happens “it’s not going to perform as you expect, and it’s going to be overwhelmed more frequently, and it’s going to be become a problem,” Bowden said.

Environmental engineer George Wood, owner of Environmental Professionals of Kill Devil Hills for nearly 40 years, told Coastal Review that private infrastructure systems in particular would be overwhelmed by more frequent and increased storm intensity and rainfall. And, compounding the problem is less recovery time for the system between storms.

Wood was particularly critical of how private stormwater systems are maintained – or not — noting that private retention ponds are often overgrown with subaquatic vegetation and culverts are often clogged and incapable of even handling the rainfall amounts for which they were designed.