A powerhouse in the marine science and coastal management community, Dr. B.J. Copeland, 89, died Wednesday, Jan. 14.

Copeland left a lasting impact on the state as the director of North Carolina Sea Grant, a N.C. State University professor, and through his work with the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership. He served on the Marine Fisheries Commission, and was on the committee that drafted what is now the Fisheries Reform Act of 1997.

Supporter Spotlight

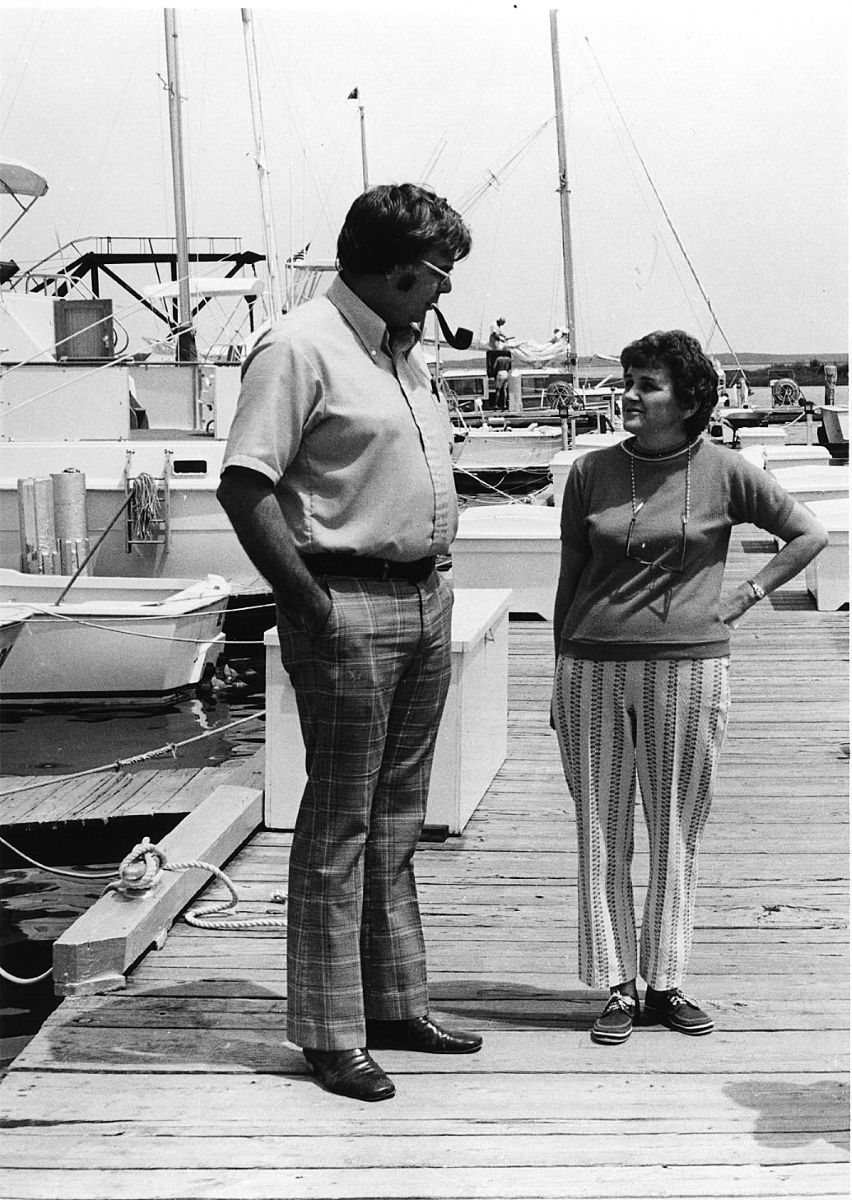

Copeland spent his childhood, along with his three siblings, on the family farm in rural Oklahoma. He earned his master’s and doctorate at Oklahoma State University, where he met his wife of more than 60 years, Jean Van Nortwick. They married Jan. 26, 1963.

He relocated to Texas in 1962 where he was a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the University of Texas Marine Science Laboratory at Port Aransas.

In a 2016 interview for the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center’s Coastal Voices Project, Copeland said his “Ph.D. degree is in Limnology, the study of fresh water. So, I went to the University of Texas to see if salt water was the same as fresh water and indeed it is, except for a little bit of salt!”

He moved to Raleigh in 1970 for an associate professor position at N.C. State. Copeland said in the Q&A that he moved to North Carolina mainly because of the beginning of a marine science program jointly between N.C. State, the universities of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Wilmington, and Duke University.

“We were trying to start a graduate program in Marine Science and so I was a researcher and a professor in the Zoology Department, Botany Department, and the new Marine Sciences program,” he said, adding that the new marine sciences program eventually became the Department of Marine, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences at N.C. State.

Supporter Spotlight

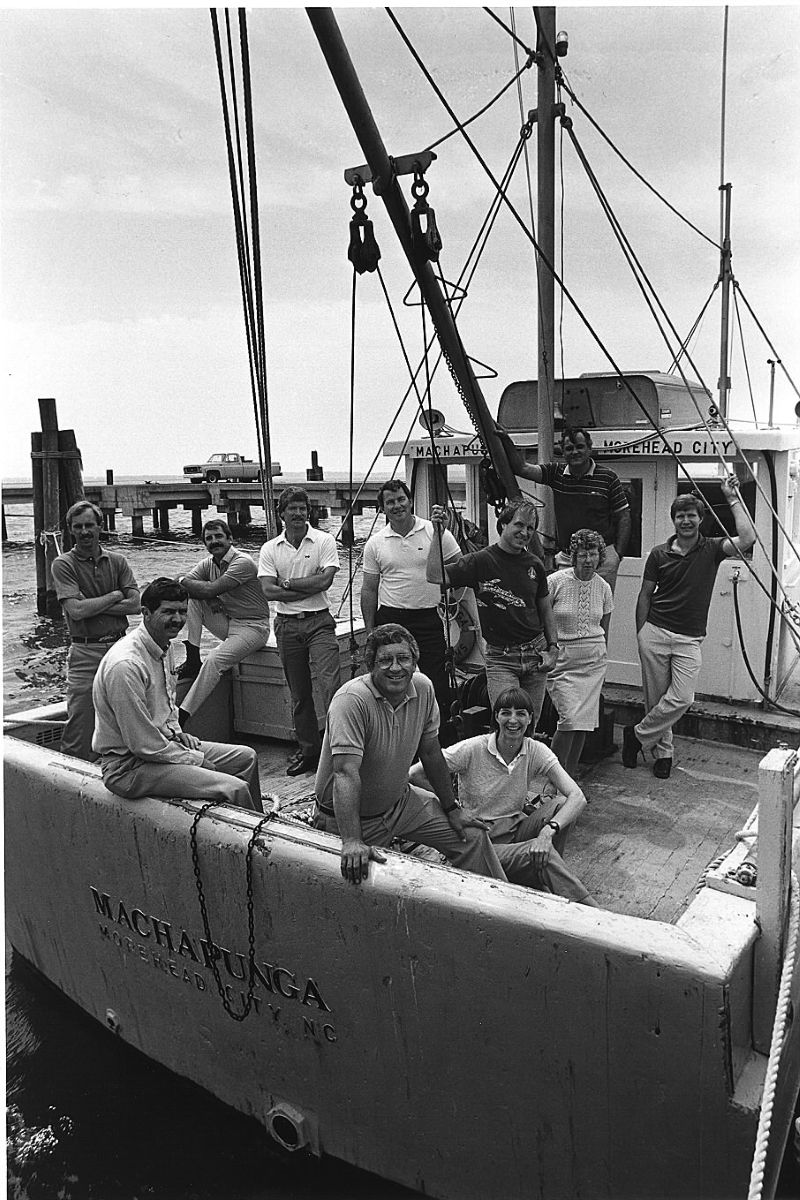

In 1973, he took on a new role as the director for what was then the North Carolina Sea Grant institutional program, explains an article on the 25th anniversary of the program in the October 2001 issue of N.C. Sea Grant’s Coastwatch magazine.

Congress established the program in 1966, and began awarding grants in 1968. Sea Grant then became part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, that was formed in 1970. UNC Chapel Hill administered the Sea Grant institutional program from 1970 to when Copeland took over and relocated the program to Raleigh.

“In truth, if Sea Grant wasn’t invented in 1966, someone would invent it today. People depend on Sea Grant for good information and to help them survive,” Copeland said in the 2001 article. “You can’t argue with priorities when they are to improve the quality of life and enhance economic opportunities. That’s what Sea Grant is all about.”

Copeland said that in the early days of trying to gather input on research and extensions needs, he talked with a man who working his eel pots and crab pots. Copeland said he asked the waterman what the program could do for him and the man responded, “’Sounds like you guys are just looking for something to do.’”

Copeland got the message, though. For Sea Grant to be accepted, the program would need to be relevant and deliver good information, he said in the article.

He began hiring staff who brought in their own experiences, leading the program to marine advisory work, promoting shellfish culture, addressing seafood processing issues, developing seafood recipes, outreach efforts, and research.

When Copeland took over the program in 1973, his goal was to elevate N.C. Sea Grant from an institutional program to be designated a Sea Grant College Program, which happened in July 1976. The program also got a budget of $1 million.

The federal-state partnership was supported with $2 in federal funds for each $1 in state funding, but in 1980, Sea Grant was zeroed out of the federal budget, leading to Copeland spending many days in Washington getting the Sea Grant message out, according to the 2001 article.

He said at the time that it wasn’t a stretch to show that Sea Grant was worth something and worth keeping.

“The direct impact was evident in the growth of the extension program. Initial work in fisheries and marine education were soon joined by aquaculture and mariculture. Coastal processes work increased, as did coastal law and policy efforts,” the article explains.

Copeland left Sea Grant in 1996 and began serving as graduate administrator for the Zoology Department at N.C. State. He retired from the university in 2002.

Current N.C. Sea Grant Executive Director Susan White told Coastal Review that she was fortunate have had Copeland as an early and regular mentor when she joined the North Carolina Sea Grant program as director in 2012.

“We had great lunches together, sometimes here in Raleigh sometimes closer to his home, and his knowledge of the intricacies of a statewide program that evolves regularly with the pressing needs of the times was relevant and timely as I was still learning the many paths for NC Sea Grant,” White said.

“B.J. always had great stories to tell about his time with NC Sea Grant, the challenges of federal funding support ebbing and flowing, the great characters of each of the team members, and his enjoyment of his time with the program. B.J. joined us for retirement parties and program reviews throughout the past decade, keeping his finger on the pulse. His practical advice, and huge laughs, were wonderful to be on the receiving end of,” she continued.

Copeland’s work with what is now Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuarine Program predates his time with Sea Grant and, once he began directing Sea Grant, his partnership with APNEP grew.

Copeland said in a Q&A with the program that he “was involved with APNEP before it was APNEP – before it even existed, in fact.” APNEP is an effort to understand, protect, and restore natural resources of the Albemarle-Pamlico estuarine system in North Carolina and Virginia, its website explains.

The only National Estuary Program in the 1960s was the Chesapeake Bay. In the late 1960s, “somebody got the happy idea that Congress ought to have an annual or biannual report on the status of the nation’s estuaries, so they commissioned one,” Copeland explained.

He went to Chapel Hill in 1968 to work on a report on the nation’s estuaries. He and the late Dr. Howard Odom wrote “Coastal Ecological Systems of the United States.”

“To do research for it, we went to every state and gathered material that had been written up or stuck in a drawer, and we took that data on coastal systems and turned it into a book. It was the first work on the status of the nation’s estuaries,” Copeland said.

A handful of Congressmen in the 1970s, including Walter Jones from North Carolina, who was chair of the House Merchant Marine and Fisheries Committee, pointed out that there’s an estuary in North Carolina.

Copeland continued that the whole setup of the National Estuary Program was changed to include not only Chesapeake Bay, but also other estuarine systems. The Albemarle-Pamlico system “includes a lot of water and a lot of territory – we were known as the second-largest ecosystem on the East Coast.”

In the early 1980s, work began on establishing the Albemarle-Pamlico as a National Estuary Program, and he helped form the first technical committee. “In 1987, we got the first grant for the program – for the Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine Study (APES). We were a part of the National Estuary Program, authorized by Congress earlier that same year,” he said.

At the time, there were water quality problems that he described as “astronomical,” with algal blooms in the Chowan River, Albemarle Sound and Pamlico River. The Neuse River had fish kills.

“We had a crisis. You couldn’t sell seafood for a year, so we had to solve this problem. You’ve got to turn this thing around or the seafood industry is going to go down the tubes – that’s the reason for the program. But what people sometimes forget is that you can’t do all this at once. You’ve got to prioritize, you’ve get something understood and you find out it’s really connected to something else over here – it’s not easy,” Copeland told APNEP. “And so, we began to work. We had technical committees and proposals for projects and for priority research, and things began to trickle into state policies and state government.”

After the technical committee completed the Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine Study and produced the Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan for the region in 1994, the project was renamed as the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuarine Program. In 2012, program was changed to partnership.

Southern Environmental Law Center Senior Attorney Derb S. Carter Jr. told Coastal Review that Copeland was leading the state’s Sea Grant program when the Coastal Area Management Act was enacted in 1974 and when the Albemarle Pamlico Estuarine Program launched.

“Effective environmental and natural resource programs must be based on sound science. We are all fortunate that B.J. was passionate about ensuring programs to manage our coastal resources incorporate the best science,” Carter said.

It was also in the 1980s when Copeland was appointed the first time to the Marine Fisheries Commission, and eventually helped draft the Marine Fisheries Reform Act in the 1990s.

In the 2016 Q&A for Carolina Coastal Voices project, Copeland said he became involved with fisheries management because Sea Grant has programs on commercial fishery, recreational fishing, interactions, management of fisheries, how things worked, and could translate research into management.

“And I got into fisheries management for real when I was appointed to the Marine Fisheries Commission in the 1980s, under the so-called, ah, Egghead Commission,” he explained, adding he served on the commission for four or five years before it dissolved.

“I mean, the state government decided that commissions weren’t really the way to go, so the Marine Fisheries Commission was actually dissolved and they started over again. And so there was legislative action to create a new commission, which kept getting things added to, and added to, and added to until we have a 19-member Marine Fisheries Commission,” he explained. This was in the mid-1980s.

“And that was also a disaster, because 19 people can’t make any kind of decision,” Copeland said.

The committee argued a lot and “what happened with the Fisheries Moratorium Act, I mean–that was one of the factors, that we had an unwieldy commission — no way to get there — we had regulations right and left, none of which were related to others. People were kind of fed up with the whole idea,” Copeland said. The fisheries moratorium “came because they wanted to stop, look, consider, and really come up with something. And so, we had a three-year moratorium on anything; on any regulation, on any activity, any new activity. And that resulted in the Fisheries Reform Act.”

The North Carolina General Assembly approved in 1994 the moratorium on selling any new commercial fishing licenses and established the 19-member Fisheries Moratorium Steering Committee to study the state’s coastal fisheries management process and recommend improvements.

The committee issued a draft report in late summer 1996, held 19 public meetings statewide, and adopted a final report in October 1996 that formed the basis for the Fisheries Reform Act, which was signed into law Aug. 14, 1997, according to the oral history project, calling it the “most significant fisheries legislation in NC history.”

Copeland was on the moratorium steering committee and as director of Sea Grant, he said he represented the research and information side.

As part of the moratorium, Copeland said, funds were appropriated for research that was administered through N.C. Sea Grant college program, and “I think I knew about all of the players. So, communication and interaction amongst the players was also important, and Sea Grant played a role in that, as well.”

Another part of Sea Grant’s role was to get the information out broadly and quickly, Copeland said they did that through a network “and we traded on two very important elements: one of them was the truth. If you’re a bearer of the truth, you usually get along pretty well. And so we had a reputation for doing that. And secondly, we thought that information was a necessary ingredient for anything we did. And so, we were doing that, too. It was kind of a natural fit.”

The committee was tasked with creating parameters for a Marine Fisheries Commission that “could actually function,” Copeland said, trimming it down from 19 to nine. The commission has three people from the commercial interests, three people from recreational interests, and three at large, all appointed by the governor. He served on the newly structured commission for 12 years.

Copeland said in the Q&A that “we were purveyors of the truth. We had a reputation of, you know, you can come and ask Sea Grant a question, you were going to get an honest answer. And so we could be a player without taking a side. And that was really important, because most people take sides somewhere, sometime. And so we worked very hard at not taking a side.”

He lamented that fisheries is going to take a hit because of misinformation, in the 2016 interview.

“Some of these environmental issues, which are going to get scuttled because of some misinformed position, somebody who’s more powerful than somebody else will get their way and so on. I mean, they practice the Golden Rule, you know: them what’s got the gold, rules. So, you know, I think things are going to get worse before they get better. I keep thinking that, one of these days the general public’s going to wake up and say, ‘We need to get rid of this bunch!’ but that’s not happening,” he said.

After the Fisheries Reform Act, Copeland said in an interview that he went back to the academic department at N.C. State and taught a couple of courses, retiring in 2002.

North Carolina Coastal Federation founder Todd Miller told Coastal Review that Copeland influenced the direction of coastal science and management in North Carolina for more than half a century.

“After ‘retirement,’ he continued to shape coastal policy and practice as a member of the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission, an active participant in the Albemarle–Pamlico Estuarine Partnership, the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan process, and numerous other civic efforts,” Miller continued. “He built a Sea Grant program in North Carolina that earned international respect and, importantly, translated coastal research into practical solutions for real-world management challenges. Through his leadership and service, he profoundly influenced efforts to protect and restore the North Carolina coast and left it stronger for future generations.”

He and his wife owned a farm near Apex from 1978 until 2002 and later a farm near Pittsboro, according to his obituary, and he found joy in gardening and farming.

“For many who knew and loved him, B.J.’s deep voice and his loud belly laugh will always be remembered. His excellent memory and quick wit made him an entertaining teller of stories and jokes. We can only hope that some of us can tell them as well as he did. B.J. will long be remembered with gratitude, admiration, love and a big smile,” his obituary states.

His memorial is at 2 p.m. Friday at Pleasant Hill United Methodist Church in Siler City.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made in memory of B.J. Copeland to: Boys & Girls Homes of North Carolina, P.O. Box 127, Lake Waccamaw, NC 28450, or Pleasant Hill United Methodist Church at P.O. Box 1322, Pittsboro, NC 27312. Arrangements are by Donaldson Funeral Home and Crematory.