Editor’s note: The following is from historian David Cecelski’s “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.” The Carteret County native introduced the nearly 20-part photo-essay series earlier this year on his website, explaining at the time that the images he selected from the N.C. Department of Conservation and Development Collection were taken in the late 1930s into the early 1950s of the state’s farms, industries, and working people.

In this photo-essay in my “Working Lives” series, I am looking at several photographs that feature workers on a railroad that old timers, when I was a boy, still called the “Old Mullet Road.”

Supporter Spotlight

The real name of the railroad was the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad (A&NC). First in business in 1858, it ran from the coastal port of Morehead City, west to New Bern, Kinston, and finally Goldsboro.

Owned by the state of North Carolina, the railroad was usually leased to private operators and it played a vital role in opening the economy and communities of the North Carolina coast to the outside world.

In Goldsboro, at the railroad’s western end, other lines connected the A&NC’s passengers and freight to Raleigh and to distant markets and cities such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York.

Local people referred to the A&NC as the “Old Mullet Road” because of the seemingly endless barrels of salt mullet that its freight cars carried out of Morehead City in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

With the opening of the railroad in 1858, the local fishery for striped mullet — what we’ve always called “jumping mullet” — grew into the largest saltwater fishery anywhere in the American South.

Supporter Spotlight

Long a staple in local pantries, barrels of salt mullet were soon as common in the country stores of eastern North Carolina as pickled pigs feet and rounds of farmers cheese.

-2-

The construction of the A&NC and the building of the coastal town of Morehead City went hand in hand.

The town’s resort trade, its famous charter fishing business, the state port, the local menhaden industry (one of the largest fisheries in the U.S.), and really the region’s entire wholesale seafood industry — none would have been imaginable without the “Old Mullet Road.”

The same could be said for the truck farming business throughout that whole central part of North Carolina’s coastal plain.

Over the years, the A&NC’s trains became part of daily life in the towns and crossroads through which it passed.

For people who lived along the tracks, the coming and going of the train, its whistle, and the sense of curiosity and wonder about what lost soul might be coming home, or what trouble might be arriving, became measures of time passing as much as the tides and the changing of the seasons.

-3-

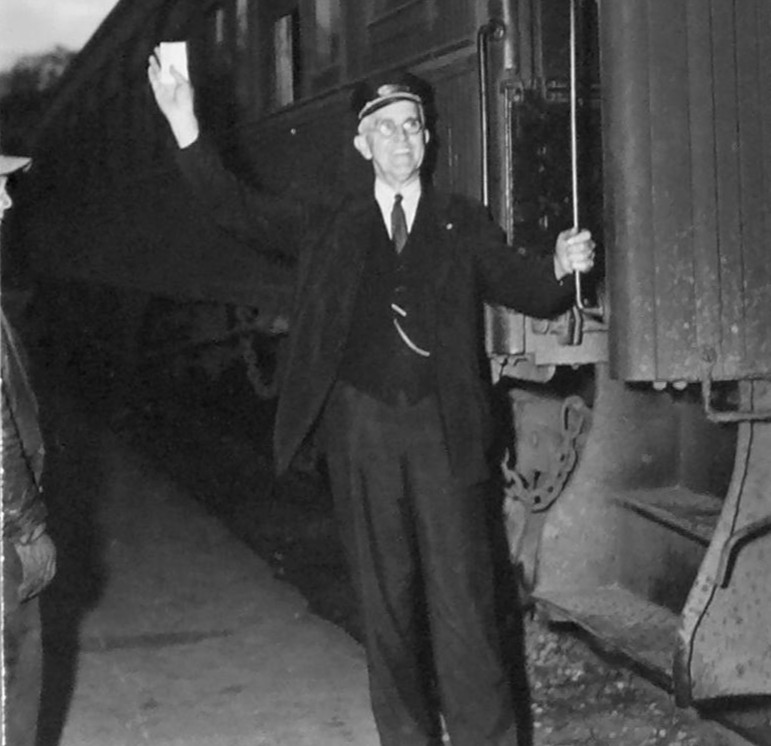

Taken in Morehead City or New Bern in 1942, this photograph introduces us to one of the railroad’s employees who was something of a legend in that part of eastern North Carolina.

His name was J. B. Davis, people called him “Captain Davis,” and he was a conductor on the railroad for close to half a century.

On Nov. 30, 1924, the Raleigh News & Observer referred to Capt. Davis and the railroad’s three other conductors as “the most popular quartet in this part of the State….”

The paper went on to say, “They know more people than all the politicians in Wayne, Lenoir, Craven, and Carteret counties.”

A railroad conductor saw the best and worst of humanity. Capt. Davis came to know the high and mighty and the utterly defeated, those that were good, and those that were set on evil, people anxious to get back home, and those desperate to get away from home.

Along the railroad’s path, people often sought him out to get the latest news from other towns. Many a day, he was the first to bring word of births and marriages, shipwrecks, hurricanes and floods.

His own life on the railroad was far from uneventful: Capt. Davis was injured in a derailment in 1933, and he and the train’s brakeman were usually the first to reach the poor souls who were killed on the railroad tracks.

In 1939, when a new company, the Atlantic & East Carolina Railroad Co., took over the railroad’s lease, Capt. Davis was fired for allegedly not collecting fares from some of his passengers.

His discharge made headlines across eastern North Carolina, and he was eventually rehired, but there has to be story there.

Maybe he was just looking out for his friends. On the other hand, times were hard in the 1930s and I like to think that maybe now and then he looked the other way and let a penniless soul or two ride for free.

-4-

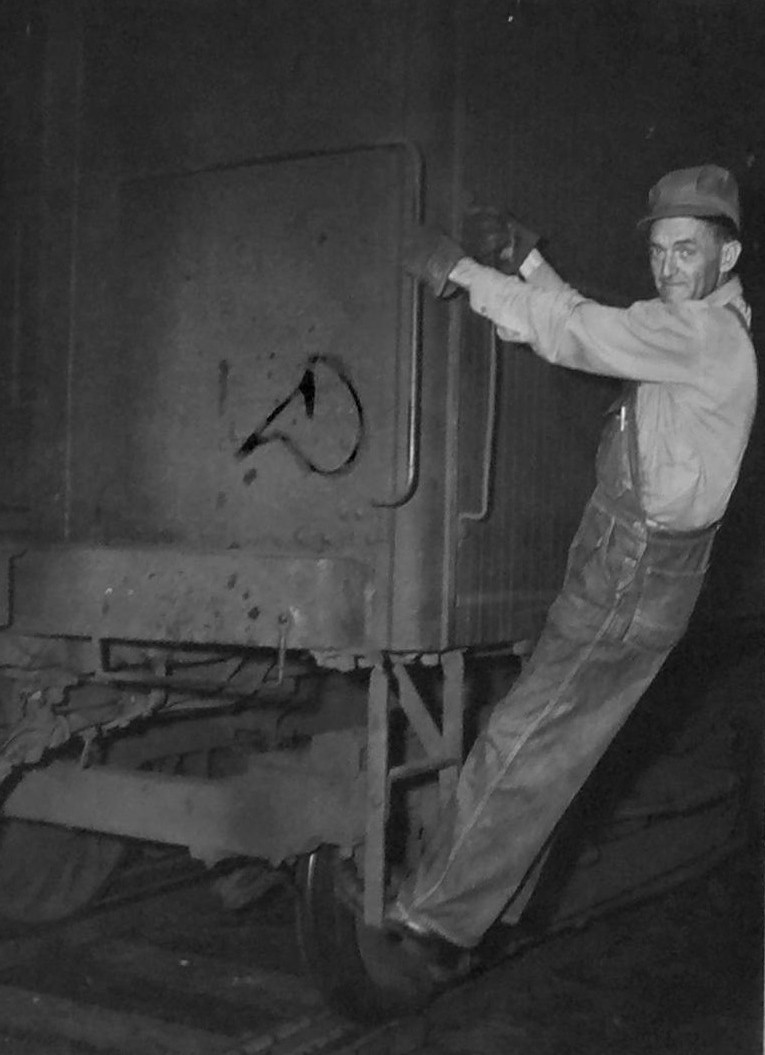

I assume that this gentleman was one of the train’s firemen, whose job it was to maintain the fire in the engine’s boiler by shoveling coal and watching the boiler’s water levels as well.

A 1947 newspaper article concerning a derailment mentions an A&NC fireman named Henry Peterson. This may be him, but I cannot be sure.

Judging from the way he holds himself, I might have thought that he was the train’s engineer, but that was not possible in eastern North Carolina in the first half of the 20th century because he was African American.

At the turn of the 20th century, the A&NC’s president was a New Bern banker and real estate mogul named James A. Bryan.

Bryan was one of the leaders of the white supremacy movement that swept North Carolina in the period from 1898 to 1900. To attract New Bern’s white working class men to the white supremacy cause, he promised to discharge all of the railroad’s black employees and give their jobs to white workers.

After the Wilmington Massacre and the victory of the white supremacists in November 1898, Bryan lived up to his promise.

According to documents preserved in the Bryan Family Papers at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Southern Historical Collection, he discharged dozens of A&NC conductors, porters, brakemen, mechanics, blacksmiths, and other skilled railroad men in 1899 and 1900.

He also fired many of the company’s lowest level black employees, including the night watchman at the company’s rail yard.

In exchange for white workingmen’s support for a state constitutional amendment that took all voting rights from the state’s black citizens, Bryan also pledged to embed white supremacy in the railroad’s labor policies into the future.

In practice, that meant: the A&NC’s managers would hire and promote whites preferentially, regardless of qualifications or experience; would never pay a black worker as much as a white worker; would never employ a black individual in a management role; and would never hire or promote a black man or woman into a job–such as locomotive engineer– that gave them supervisory responsibilities over any white employee.

The railroad’s policies with respect to race were still in place in 1942.

You can learn more about James A. Bryan’s leadership in New Bern’s white supremacy campaign, and see some of the manuscripts related to his firing of the A&NC’s black workers, in my essay, “The Other Coup D’Etat: Remembering New Bern in 1898.”

-5-

Only a few years before these photographs were taken, the railroad had seemed on its last legs.

The private railroad company that had leased the track from the State of North Carolina since 1904, the Norfolk & Southern, had defaulted in 1934, a victim of the Great Depression.

After the Norfolk & Southern’s default, state coffers could not keep up with the railroad’s maintenance and repair needs. Years of neglect began taking their toll: broken railroad ties abounded, embankments needed reinforcement, and much about the old railroad seemed frayed and worn out. Reports of derailments grew more common.

Things began to look up in 1939 however, when the state finally found a new private company to take over the railroad’s lease.

The new company, the Atlantic & Eastern North Carolina, invested in new engines and track repairs, updated at least some depots, and even repainted the cars a perky “Spanish blue” instead of the old dull black.

-6-

Then the war came. Everybody was on the move. Soldiers, sailors, defense workers, and civilians of all kinds.

A new prosperity was in the air, heightening the demand for carrying passengers and hauling the region’s agricultural products and other freight.

Probably most importantly, the federal government began constructing two massive new military installations on the central part of the North Carolina coast in 1941 and ’42. To build the two bases, the railroad’s freight cars would carry enough lumber, brick, piping, and other construction materials to build two good-sized cities from scratch.

The railroad ran a short spur from Havelock Station into the construction site for the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station (originally called Cunningham Field). To the south, the railroad carried construction materials to Camp Lejeune via a track that ran from New Bern to Jacksonville, then along a short spur owned and operated by the Navy.

By the time these photographs were taken, the railroad was making a profit again for the first time in recent memory.

-7-

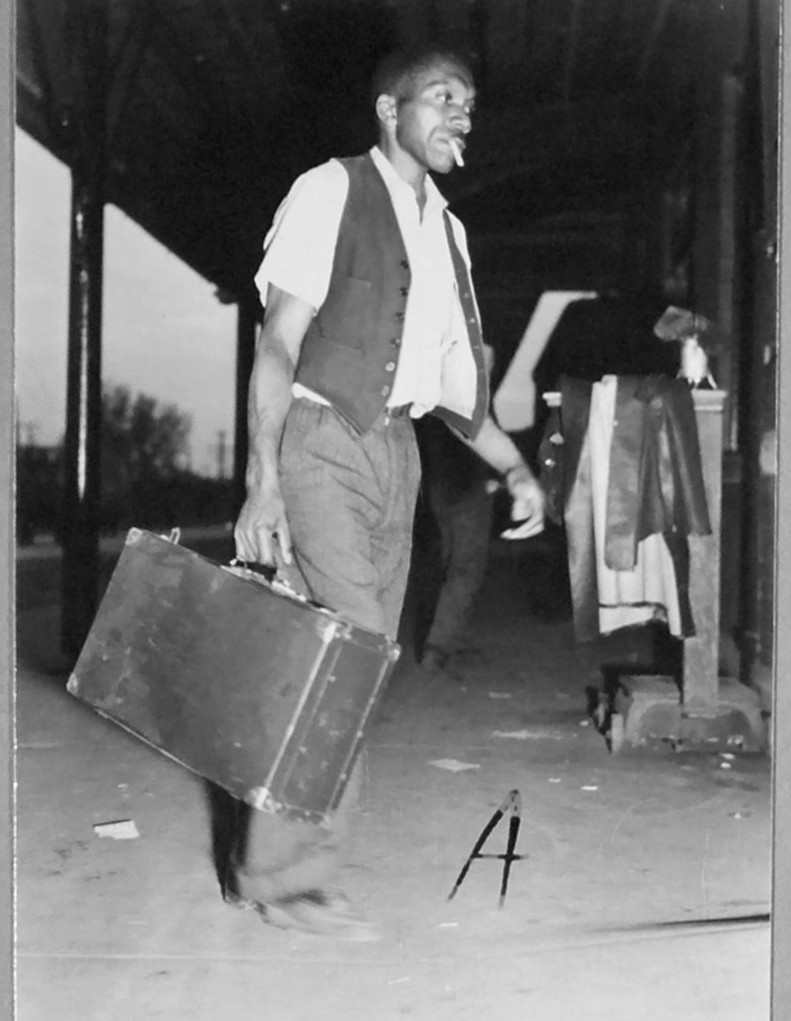

The war changed the railroad and the North Carolina coast in a thousand ways, some easy to get used to, and some that probably haunted the workers that we have met here — Capt. Davis, the fireman, the mail clerk, the brakeman, and the porter in the photograph above — for their rest of their lives.

More than 25 years ago, I interviewed an elderly woman named Gretchen Brinson in Morehead City.

During the early part of World War II, Ms. Brinson had been a nurse in the burn unit of the town’s little hospital when German U-boats were sinking merchant vessels off that part of the North Carolina coast.

This is an excerpt from that interview:

“I married Bull Brinson in 1937. While my daughter was still an infant, I started working at the hospital. Very shortly, we began hearing depth charges and if they had a strike we could see the fires, the ships burning.

“The debris washed up on the ocean front, and there were several years we couldn’t swim up there because of the debris and the oil slicks.

“We could see the ships burning.

“When there was a strike out there at night, we knew this had happened and that next morning there would be casualties come in. Bodies, corpses did wash in on the beach. And they were brought into the hospital: burns, all manner of traumatic situations. The hospital was full. It was only a 30-bed hospital. They lay in the hall on cots. We were not prepared for the onslaught.”

She continued:

“Many of the young men who came here, son, did not live. When the 3 o’clock train left town, the baggage car doors were most always open, and you could see several coffins in their wooden boxes, being shipped to other places. There was seldom a day for months, maybe a year or more, when there were not one or two or three or possibly more that went out on that 3 o’clock train.”

-End-

My story “Gretchen Brinson: A Born Nurse” originally appeared in my “Listening to History” series in the Raleigh News & Observer on June 14, 1998. You can find a copy of the story here.