The Indian Woods historical marker at the intersection of St. Francis Road and U.S. Highway 17 in Bertie County is easily missed while cruising at 55 or 60 miles an hour.

Located at the edge of a farmer’s field after the fall harvest of cotton, the sign leans to the north, and hints of the story and its aftermath of an almost forgotten war between Native Americans and colonists in the early 18th century.

Supporter Spotlight

It is the northernmost of at least seven signs that are found throughout coastal North Carolina from Wayne County to Bertie County that trace the story of that conflict.

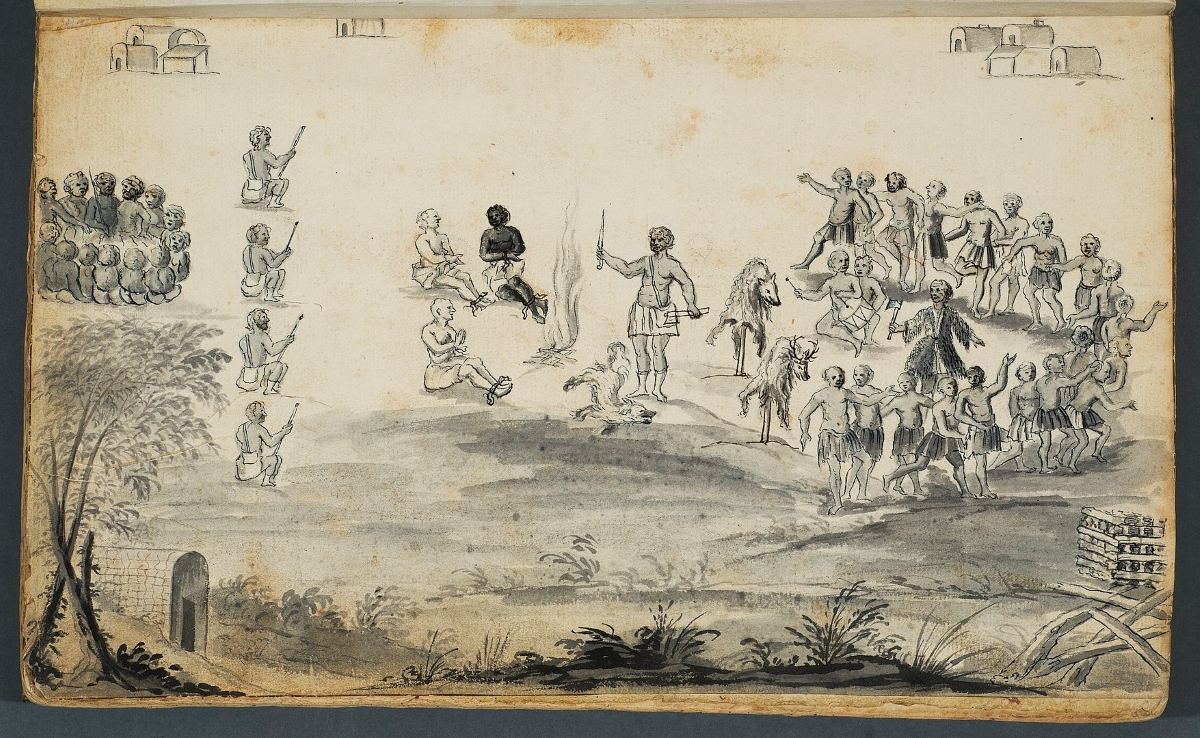

The Tuscarora War was brutal and horrific. Launching a coordinated attack on the morning of Sept. 22, 1711, Tuscarora warriors slaughtered 140 men, women and children throughout eastern North Carolina.

“The Tuscarora devastated white settlements in the Pamlico Neuse region and raised serious fears for the continuance of English occupation in North Carolina,” Thomas Parramore wrote for the North Carolina Historical Review in 1982.

Unable to defend its own people, the North Carolina colony’s general assembly begged Virginia and South Carolina for help.

Virginia refused to send troops, but put pressure on neutral Tuscarora villages in its colony to remain out of the conflict. South Carolina sent combined white and Native forces.

Supporter Spotlight

In the end in March of 1713, when the last pitched battle of the war was fought at Fort Neoheroka, which is present day Snow Hill in Greene County, at least a thousand Tuscarora were dead and another thousand sold into slavery in South Carolina.

In North Carolina, as many as 200 colonists were killed and the combined white and Native combatants provided by South Carolina suffered an additional 200 deaths.

Tuscarora lineage

The Tuscarora were part of the Iroquois, whose original lands stretched from New York state into Canada. The migration to North Carolina most likely occurred sometime around the 1500s, Dr. Arwin Smallwood, dean of the College of Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at North Carolina Central University, told Coastal Review.

Smallwood, who traces his lineage to the Tuscarora people, grew up in Indian Woods and has studied the history of the Tuscarora extensively.

“In the 1500s they’d already moved down from (New York) and settled North Carolina,” he said, adding that “they never broke their blood ties to the five nations,” which are the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca.

By the 1580s, when Sir Walter Raleigh’s doomed expeditions landed on Roanoke Island, the Tuscarora were well established in eastern North Carolina and probably were the dominant Native nation of the region. They may have been the ones who decided the colony’s fate.

“Tuscarora oral traditions say they were the ones who destroyed the Lost Colony,” Smallwood said. “They always had large numbers of people who had European characteristics like red and auburn hair, even sometimes blonde hair, but definitely what (Native Americans) called the Tuscarora eye, which was blue-green, kind of a hazel eye, that was prevalent throughout the Tuscaroras and that distinguished them.”

War: Longtime complaints

At its simplest, the Tuscarora War was about long-established complaints of the Tuscarora: Encroachment on lands they had traditionally controlled and unfair and dishonest trading practices.

But, Smallwood noted, there were other factors at play.

It was “trade routes. The Tuscaroras controlled the Piedmont and the coastal plains of North Carolina. They controlled all the major trade routes between North Carolina and Virginia,” he said. “Anyone who needed knives, axes, guns, gunpowder, whatever they had to trade through them, including rum. They had to trade through the Tuscaroras. For the southeastern Indians, it was a way of eliminating them as the people who monopolized trade.”

It is possible that, after at least 60 years of observing the internal politics of the North Carolina colony, the Tuscarora were aware of the internal rivalries that were threatening to tear the colony apart, and that may have played a role in the timing of the initial attack.

Cary’s Rebellion pitted Thomas Cary, the Quaker-leaning former governor of the colony, against Edward Hyde, who the Lords Proprietors had selected to govern the colony. The rebellion exposed the deep political divisions within the colony that led to open warfare with Hyde finally taking the reins of the governorship in 1711.

At that time, the colony was divided into two counties: Albemarle in the north and Bath in the south. Although in 1711 the nominal capital of the colony was Bath. There was no government office there and it’s doubtful if the population of the town ever reached 300 people.

The northern Albemarle colony was dominated by the supporters of Hyde and the resentment from Cary’s attempt to wrest control of the colony permeated the region.

“The Cary Rebellion had pitted Albemarle against Bath and had left the colonists of the two counties somewhat at odds with each other. It was by no means clear that Albemarle would rush to the defense of Bath County and, in fact, it did not,” Parramore wrote.

If there was a proximate cause of the war, it was the settlement of New Bern by Swiss immigrants and members of the Palatine religious sect escaping religious persecution in Europe.

“New Bern was built on what (the Tuscarora) considered to be part of their capital city,” Smallwood said.

Baron Christopher DeGraffenreid, the founder of New Bern, in his “Account of the Tuscarora War,” touched on many of the issues that have been cited as causing the conflict.

“What caused the Indian war was firstly, the slanders and instigations of certain plotters against Governor Hyde, and secondly, against me, in that they talked the Indians into believing that I had come to take their land,” he wrote. “Talked them out of this and it was proven by the friendliness I had shown them, as also by the payment for the land where I settled at the beginning (namely that upon which the little city of New Bern was begun), regardless of the fact that the seller was to have given it over to me free.”

Captured with surveyor John Lawson, DeGraffenreid was able to talk his way out of imprisonment and possible death.

It is possible Lawson could have avoided his fate, but, Smallwood said, “he quarreled with the chiefs. You’re being held prisoner, and you’ve been put on trial, and then you go argue with the prosecuting attorney and the judge who decides whether you live or die.”

Lawson, whose book “History of North Carolina” gave accurate and clear-eyed accounts of Native life in the colonies, was not so lucky, and may have had a hand in his own undoing. Accused by his captors of surveying the Tuscarora land for the purpose of selling it, he was tried and convicted and sentenced to death.

Like the North Carolina colony, the Tuscarora had internal divisions. Parramore described the Tuscarora as “not a nation and probably not even a confederacy though colonial perceptions of them had not traditionally recognized any significant internal divisions.”

Smallwood, however, paints a different picture.

“The whole structure was family based,” he said. “With that being said, they were all united because the whole nation is united by blood.”

Within that nation family, there were specific ways to make decisions that would affect all members for the Tuscarora nation, Smallwood said, describing the decision-making process as “a democracy.”

Smallwood explained that Lawson was convicted after “all of the chiefs met in the war council. In that council, they all agree to execute Lawson.”

War: First conflict

When the war first broke out in 1711, South Carolina sent military aid. Col. John Barnwell left South Carolina with “30 white men and nearly 500 Indians,” the Carolana website states.

Although Barnwell may have included giving military aid to North Carolina in his reasoning, by his actions and those of the men under his command, the profit that could be realized from the bounty on scalps and selling Native Americans into slavery was an important part of why he made the trip.

Thomas Peotta in his 2018 doctoral dissertation, “Dark Mimesis: A Cultural History of the Scalping Paradigm,” at the University of British Columbia, describes how profitable scalps and prisoners could be.

“Virginia and Carolina offered scalp and prisoner bounties to militiamen and allied Indians. Virginia…offered £20 per scalp to British colonists, while uninvolved Tuscaroras on Virginia’s frontier were offered a bounty of 6 blankets apiece…for the scalps of Hancock’s warriors, and market prices for enslaved women and children,” he wrote.

For Barnwell, the scalps had an additionally benefit, Peotta wrote, noting that “scalps and prisoners also offered a way to tally the dead: Barnwell’s forces recorded 52 scalps and 30 captives after (his) victory at Torhunta in 1712.” Torhunta is present day Pikeville in Wayne County.

After a series of battles with the Tuscarora including a 10-day siege at their main settlement in Craven County, Barnwell reached an agreement with the Tuscarora combatants to pay tribute and lay down their arms. After signing the agreement, he invited some of the local Indians, who had not attacked the colonists, into his camp. They were then seized, DeGraffenreid wrote, and sold into slavery

“He thought of a means of going back to South Carolina with profit, and under the pretense of a good peace he enticed a goodly number of the friendly Indians or savage Carolinians, took them prisoner at Core Town (to this his tributary Indians were entirely inclined because they hoped to get a considerable sum from each prisoner) and made his way home with his living plunder…This so unchristian act very properly embittered the rest of the Tuscarora and Carolina Indians very much, although heathens, so that they no longer trusted the Christians,” he wrote.

War: Conclusion

The action reignited the war, with King Hancock again leading the Tuscarora aligned with him. Renewing the conflict may have been justified, but it was not sanctioned by the war council, allowing the northern Tuscarora to remain neutral.

It would take another military expedition from South Carolina, this one led by Col. James Moore to end the war, but it also led to an open rift between King Hancock and the northern Tuscarora.

King Hancock was captured by northern Tuscarora at the orders of Chief Blunt (or Blount) in November of 1712 and turned over to North Carolina authorities who executed him.

The war did not end with Hancock’s death, however.

The agreement with Blunt was that he was to deliver the scalps of key leaders to North Carolina authorities by the end of the year. When he failed to do so, Moore renewed his campaign.

Finally, following a three-day siege at Fort Neoheroka the war came to an end, although there were sporadic raids and fighting until 1715.

Aftermath

For the tribal nations that had aligned with the South Carolina expeditions, their participation sparked “a continental war in the back country,” Smallwood explained.

“Because of the role,” Smallwood continued. “Those Indians in that area played in the war, it set off a continental Indian War. he Mohawks, the Oneidas, the Onondaga, the Senecas, and (allied tribes) came south, and they completely obliterated the (the southern tribes).”

In North Carolina, the war was a harbinger of extraordinary change. Initially the war’s end brought brought economic hardship to what was then called Bath County, an area that now includes Beaufort, Hyde, Bladen, Onslow, Carteret and New Hanover counties.

“The concentration of Indian attacks on frontier settlements during the war and the continuation of raids after the peace of 1713 stifled economic growth in Bath County and contributed to temporary food shortages throughout the colony,” Christine Styrna explained in a 1990 doctoral dissertation at the College of William and Mary.

But if the initial effect was to wreak havoc on the colony’s economy, the war also “provided certain colonial leaders with the opportunity to reinforce their economic and political power while serving as a catalyst for economic development,” Styrna noted.

Bath and New Bern had taken the brunt of the Tuscarora raids, and there, Styrna wrote, “colonists slowly rebuilt their homes and fortunes.”

The rest of the colony, though, experienced a “boom period” in which coastal and local trade increased dramatically. According to the shipping reports Styrna cites from the Boston Newsletter, “the number of vessels sailing to and from ports in North Carolina ports elsewhere between 1716 and 1720 increased fourfold in comparison to the five-year period before the war.”

If, however, North Carolina was on the road to recovery, the fate of the Tuscarora was one of enslavement and exile, leading to a diaspora of the tribal nation that stretched from North Carolina to Canada.

Most of the southern Tuscarora emigrated north. The largest group returned to the Iroquois in New York, becoming numerous enough that in 1722 the Tuscarora became the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy.

As they moved north, some settled in Pennsylvania. There is today, a Tuscarora Mountain in south central Pennsylvania.

Many of them, though, settled in small communities throughout North Carolina and other states east of the Mississippi.

“It’s like you take a plate or mirror and you drop it on the floor and it shatters and shards go everywhere,” Smallwood said. “There’s some big chunks, and then there are lots of little chunks. And those little chunks, are scattered all over eastern North Carolina. They’re at least today, seven different factions of Tuscaroras that are (in North Carolina). And larger groups of them who are in Virginia, and even over into eastern Ohio.”

Coastal Review will not publish Thursday and Friday in observation of the Thanksgiving holiday.