Editor’s note: The following is from historian David Cecelski’s “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.” He introduced the nearly 20-part photo-essay series in early August, explaining at the time that the images he selected from the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development Collection were taken between 1937 and 1951 of the state’s farms, industries, and working people. More of the series can be found on his website.

Like all the photographs in this “Working Lives” series, these next few photographs are also from the N.C. Department of Conservation and Development Collection at the State Archives.

Supporter Spotlight

However, this set of photographs is more personal for me than most of the other photographs that I have featured here: they were taken at my great-uncle George Ball and his brother Raymond Ball’s potato farm in Harlowe.

Uncle George, as my mother called him, was married to my grandfather’s sister Lizette. Their farm was on one side of the Harlowe Canal, while my grandfather and grandmother’s farm was on the other.

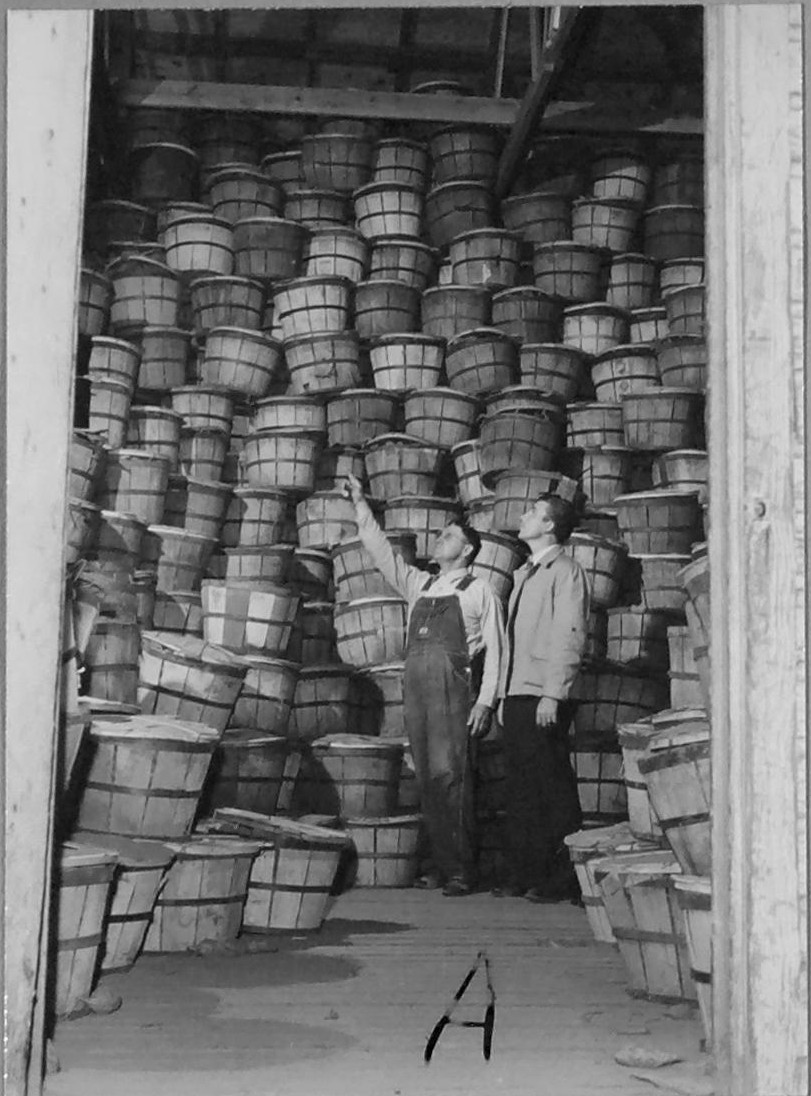

These photographs were taken in November 1942. In this first one, Mr. Raymond is standing on the left in front of a wall of bushel baskets. This is evidently the farm’s curing barn and the baskets are full of sweet potatoes.

According to the photographer’s notes, the other individual is J.Y. Lassiter, who I believe was a county farm agent.

-2-

Supporter Spotlight

Here we see two young African American men harvesting sweet potatoes at the Ball brothers’ farm in Harlowe, November 1942.

Old timers have told me that 300 to 350 men, women, and children worked for the Ball brothers at harvest time back in those days.

Most were local people, the large majority of them African American families that resided on the west side of Clubfoot Creek.

The Balls sometimes hired migrant laborers from Florida as well. When I was young, you could still see the ruins of the barracks where they stayed.

During the war, when these photographs were taken, Great-Uncle George and his brother also employed German prisoners of war.

My mother sometimes worked in the farm’s packing shed when she was a girl. She often told me about working alongside the young German men.

Harvesting sweet potatoes was no easy thing, and I have met farm people that would rather do just about anything else.

-3-

The Ball brothers were what in those days were called “progressive farmers.”

According to an article that was published in Carolina Co-operator magazine in August 1939, the Balls first invested in a tractor, an International Harvester Titan 10-20, in 1919.

In a family reminiscence, I learned that the tractor had a top speed of 3.5 miles per hour and made so much noise that locals looked at the “IHC” painted on the front, for International Harvester Co., and said it stood for “In Hell Continuously.”

The Balls were evidently the first farmers in Carteret County to own a tractor.

They were also at the forefront of other local innovations in farming that were transforming agriculture in the first half of the 20th century.

According to the Carolina Co-operator, they were among the county’s first farmers to use manufactured lime to fertilize reclaimed land, instead of burnt oyster shells and hardwood.

Similarly, they were among the first local farmers to build a modern irrigation system, to practice crop rotation, and to invest in farm machinery such as an oil burner for their curing barn and an automatic hay bailer.

By the time of this photograph, they had upgraded their tractor to a big 3-ton machine, but it is nowhere to be seen in these photographs. All we see in them are plow horses and field workers.

In the second photograph above, and in our next photograph, we see plowmen breaking up the ground, then other field hands, called diggers, following behind, often on their hands and knees.

They are digging the sweet potatoes out of the upturned ground by hand, cleaning them off, and placing them in bushel baskets.

-4-

This is another view of the sweet potato harvest at the Ball brothers’ farm in Harlowe, November 1942.

According to the article in Carolina Co-operator, the Ball brothers only grew three crops: white potatoes, sweet potatoes, and cabbage.

After the harvest, the Balls cured their sweet potato crop for several months. Then, late in the winter and early in the spring, they trucked the crop to markets in Petersburg, Richmond, and Washington, D.C.

Some years ago, near the end of his life, I sat down with my great-uncle George’s son Billy Ball and talked about his family’s history on that land.

Cousin Billy told me that his father George Ball, his uncle Raymond, and two of their brothers had bought almost 350 acres there on the north side of the Harlowe Canal on credit in 1917.

It was an abandoned farm that had grown up in sweet gum and pine. Before that time, the Balls had been living in South River, a little to the east.

At that time, only 15 acres of the abandoned farm remained cleared. The Ball brothers built makeshift shelters for themselves and their mules, and they, and presumably a great many Black men from North Harlowe, began timbering, grubbing, and clearing the land.

The Balls didn’t make much money farming at first, but they sold the timber to make the payments on their bank loan.

George and Raymond’s two brothers eventually left the farm. Billy told me that it was too hard for them and they wanted a different kind of life.

Billy told me about the days when hundreds of people worked in the fields. He recalled that his father and Mr. Raymond took trucks to North Harlowe to pick up the workers, then carried them home in the evening.

He remembered the men and women from North Harlowe bringing their lunches in lard pails, often just collard greens and corn dumplings.

-5-

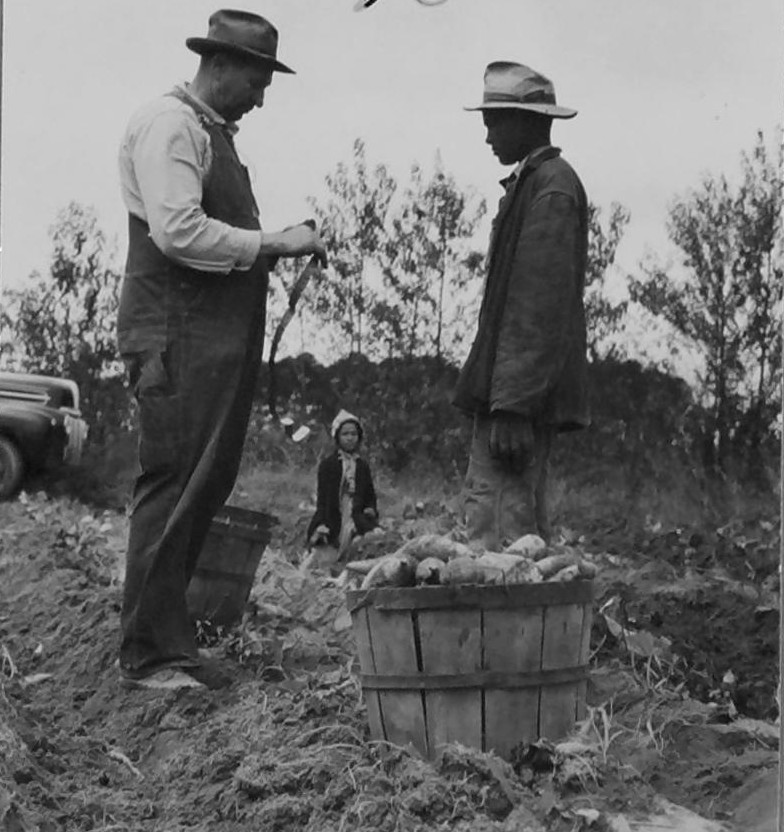

In this photograph, we see my great-uncle George Ball paying one of his harvest workers in scrip.

According to the photographer’s notes, my great-uncle and his brother paid their field workers 5 cents a bushel.

I do not know how or when the field workers redeemed the scrip. Perhaps they exchanged it for cash at the end of every workday or work week, or even after the harvest was completed.

Before the war, many of my family’s African American neighbors had few other options other than working in the fields.

By the end of 1942, when these photographs were taken, that was beginning to change largely because of the construction of the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station 11 miles to the west.

Thousands of civilians, of all races, found jobs at Cherry Point. To try to compete with the federal dollars, farm wages would have to go up, and many a white farmer that failed to treat his or her black workers with the respect or dignity to which they were entitled soon found themselves short on labor.

-End-