Anne Edwards’ grandmother rarely spoke about the young man wearing a Navy “Crackerjack” uniform in the photograph displayed on a table in the living room of her New Bern home.

As a child, Edwards would hear her mother occasionally refer to him as “uncle.” From what other relatives said, he was a sociable, kind man.

Supporter Spotlight

“There’s not a whole lot,” Edwards said. “My mother and grandmother really didn’t talk about it a lot. All I knew was that he died in Pearl Harbor.”

His photo from the table has since gone missing. The Navy does not have an official photo.

His death was untimely, violent — his remains could not be identified and returned to his family for burial. The pain of it all was likely too much for them to convey in conversation, Edwards assumes.

Last week, Edwards attended her great-uncle’s burial with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. The Oct. 8 ceremony was held more than 80 years after he was killed in the attack that thrust the United States into World War II.

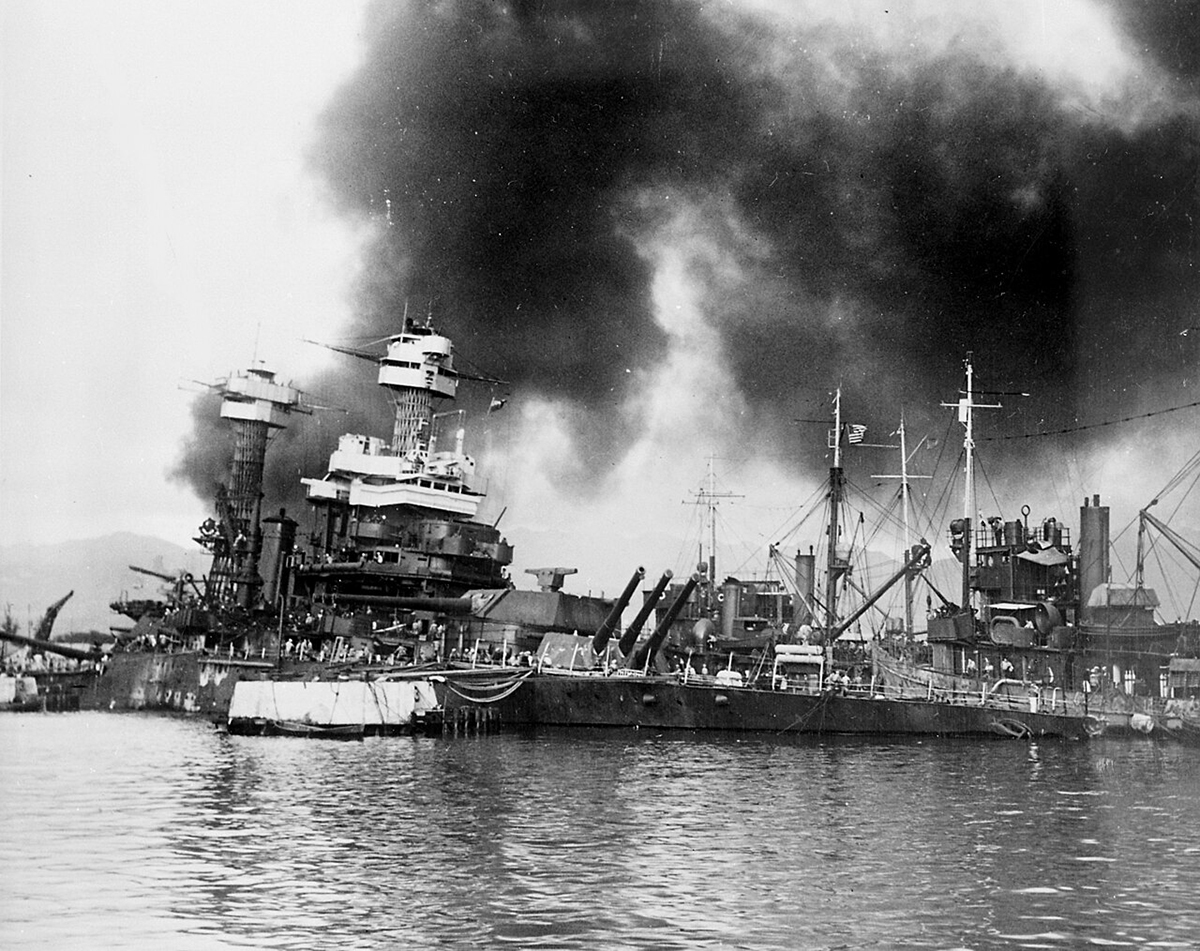

Navy Fireman 1st Class Edward Bowden was aboard the USS California on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor near Honolulu, Hawaii.

Supporter Spotlight

Early in the raid, two Japanese aerial torpedoes slammed the ship’s forward and aft, ripping a 40-foot hole in her hull. She would later be hit by a bomb that further opened her insides to flooding.

The attacks claimed the lives of 103 of her crew, including Bowden, a 29-year-old New Bern native. Bowden bore a striking resemblance to his sister who had raised him from the time he was roughly 10 or 11 after their parents died.

That would be about as much as Edwards would know about her late great-uncle, who died about three years before she came into the world, until a letter from the U.S. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency arrived at her Onslow County home more than six years ago.

Edwards called the agency, which works to identify the remains of unknown prisoners of war and those missing in action. She wanted to make sure the letter, one that requested a sample of her DNA, wasn’t some kind of a hoax.

It wasn’t.

This past April, Edwards got the call that Bowden’s remains, long since buried as an unknown at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii, were officially identified as those of her great-uncle.

She now has a document some two inches thick that contains details about the young man in the black-and-white photograph that was a staple in her grandmother’s house.

Bowden was 28 when he enlisted in the Navy on Aug. 28, 1940, in Raleigh. He reported to the USS California by November of that year.

His sister, who was 18 and married when he moved in with the young couple, signed an affidavit as his guardian, according to the paperwork provided by the casualty office.

Records do not reveal where in the ship Bowden was when it was hit and eventually sank to the bottom of the harbor three days after the attack.

Navy personnel recovered the remains of the ship’s crew between December 1941 to April 1942.

“The problem with identification came because their remains were comingled and so they didn’t really know who they were,” Edwards said.

In all, there would be 20 unresolved casualties from the USS California and 25 associated unknowns buried at the National Cemetery of the Pacific.

Remains of servicemembers yet to be identified in the cemetery were all exhumed by March 2018. As of August, 10 had been identified as being from the USS California.

Edwards was given the discretion to decide where her great-uncle’s remains should be buried.

“Now he can always be found,” she said. “That’s the reason I chose Arlington. I want any family that might be out there related to him to be able to trace him and find out about him.”

Bowden’s military awards include the Purple Heart Medal, Combat Action Ribbon, and World War II Victor Medal.

Edwards was joined by more than a dozen relatives for the Oct. 8 burial. Nieces, nephews, their children, cousins and their spouses traveled from New Bern, Greenville and Maryland to the exceptionally manicured grounds of the cemetery marked by rows and rows of glistening white crosses.

“It was unbelievable,” she said. “Everything was perfect. I was very, very pleased that the young people from the family came. I was very pleased that they felt like they should honor him. I felt a sense of closure for him. He’s not just a name anymore.”