Note from the author: This is the second photo-essay in a series I’m calling “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.” You can find my introduction to the series here or here.

In this second group of photos, the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development Collection photographers introduce us to workers in a sawmill, a handle mill, and a veneer plant that were located on the banks of the Roanoke River in 1938 and 1939.

Supporter Spotlight

During the late 19th and early 20th century, wood mills seemed to be up every river and creek on the North Carolina coast turning out lumber, shingles, veneer paneling, and, as we’ll see, even ax handles.

At the industry’s zenith around 1900, tens of thousands of men worked in those mills.

Millions of acres of forest were cut. Thousands of miles of railroad track were built to carry logs to mills and lumber to distant markets. Towns rose, and often fell, with the opening and closing of mills.

I was drawn to this photograph, and to the others below, because they give us a rare glimpse at the people inside those mills.

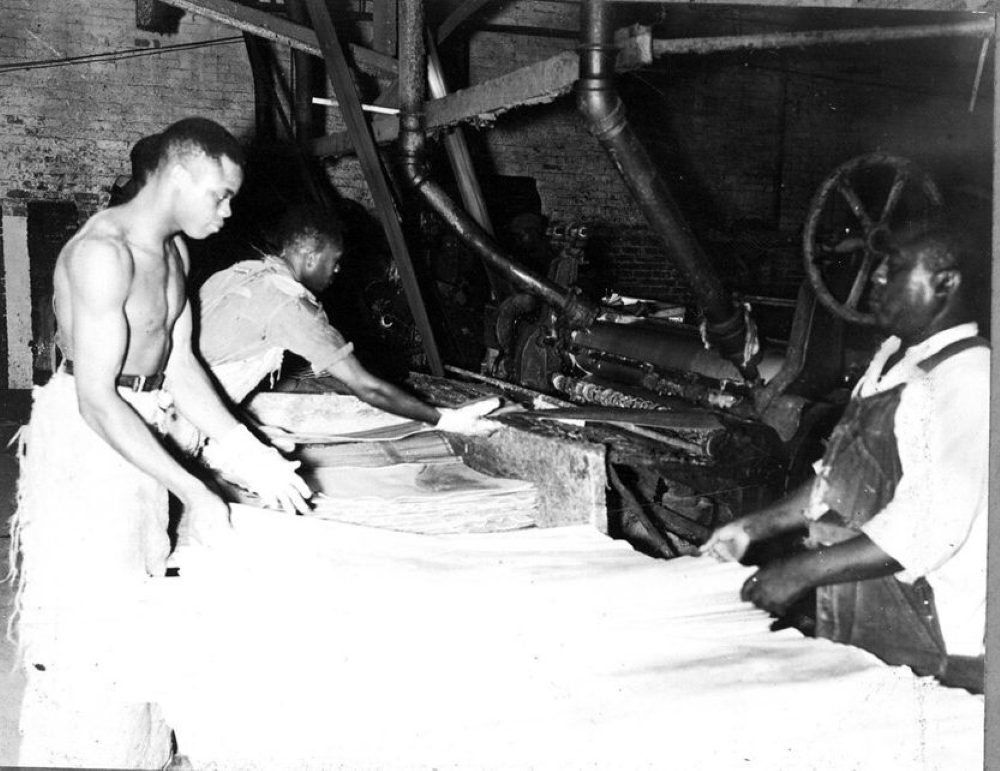

In this first photograph, we see two young men and an older gentleman cutting and stacking veneer panels at the Weitz Veneer Co.’s plant in Plymouth in 1938.

Supporter Spotlight

Based in Chicago, Weitz had made veneer paneling in Plymouth since the turn of the century.

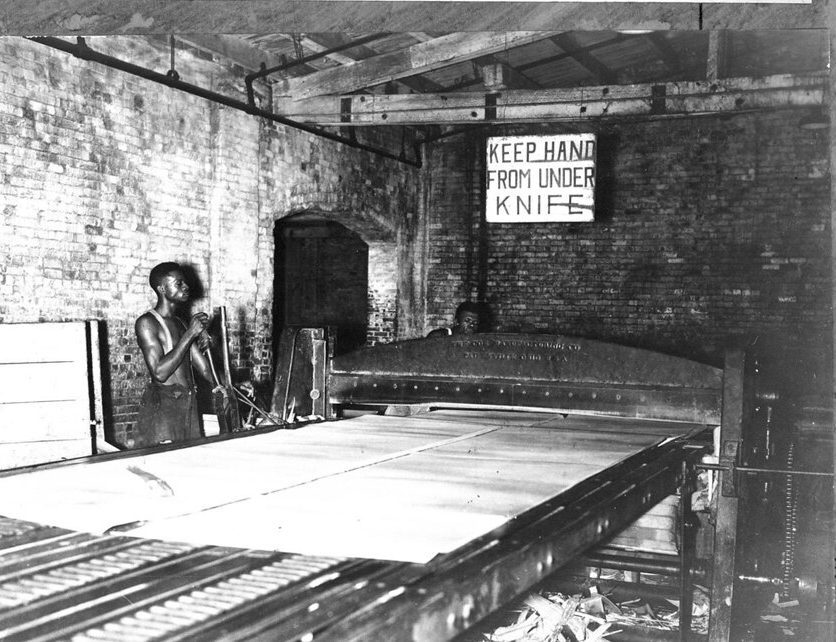

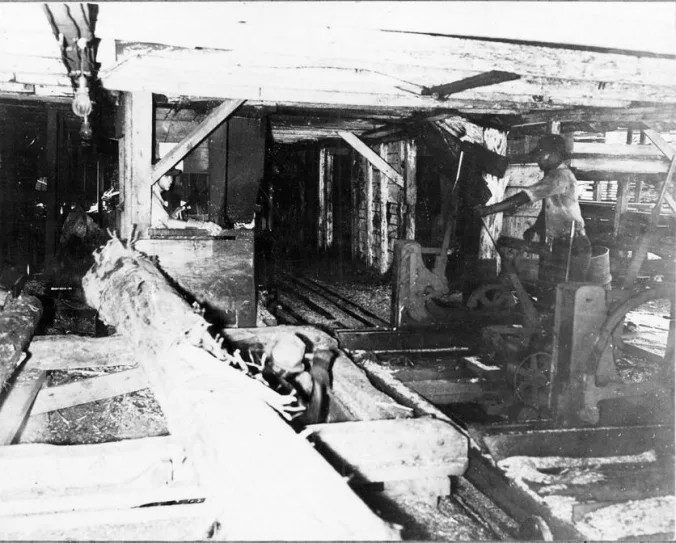

The work was hard, exacting, and much of it required great skill. It was also notoriously dangerous. The rate of accidents was especially high in the furnace and boiler rooms and for those, like the men in this photograph, who operated lathes, planers, and other cutting machines.

At Weitz, the making of veneer began by sorting, debarking, and cutting raw logs into boards.

The company’s workers then used rotary lathes and slicing machines to cut the boards into thin sheets of veneer. Once that was done, they dried the veneer in kilns, then cut and fashioned the panels into whatever size and shape that was appropriate for the final product.

From there, the workers handed the veneer panels over to the finishing department, where other workers sanded and often stained or coated them in some way before other workers assembled them.

According to newspaper reports, the Weitz plant’s workers were largely using the veneer to manufacture wooden boxes when this photograph was taken in the late 1930s.

-2-

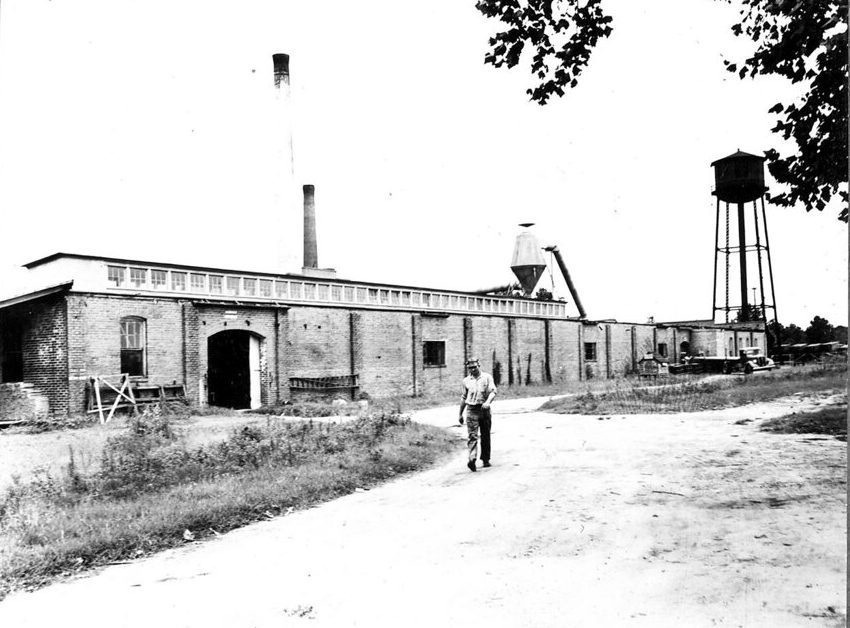

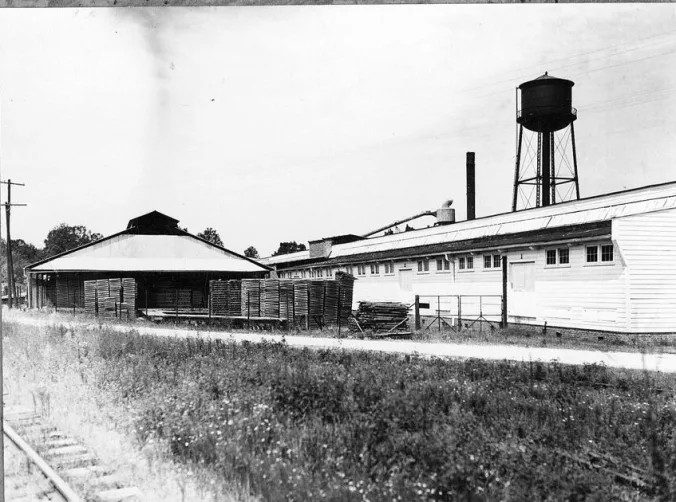

In this photograph, also from 1938, we see the Weitz Veneer Co.’s plant from the outside, a lone man strolling by.

The Roanoke River and the company’s wharf is on the other side of the plant. Down the road, but not visible in this photograph, was a section of company housing called White City.

Plymouth was booming in those years just before World War II. Large numbers of people were migrating to the little river town to work in the lumber and wood products industry.

Some came to Plymouth to work at Weitz or one of the town’s smaller wood products companies. Most, however, were looking for work at a massive new pulp mill that had opened in Plymouth in 1937.

A division of a large corporation based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the North Carolina Pulp Co. had built the pulp mill on the banks of the Roanoke, 3 or 4 miles upriver of the Weitz plant.

Some of the town’s new residents came to Plymouth from towns where other mills had closed. A sizable contingent of workers from a shuttered mill in West Virginia, for instance, moved to Plymouth to take jobs at the pulp mill.

But hundreds of others were African American families that had forsaken sharecropping or tenant farming elsewhere in eastern North Carolina to make a new start at Weitz, the pulp mill, or one of the town’s other companies that were connected to the lumber industry.

At Weitz, the work was sweltering hot in summer, freezing cold in winter, ill paid, and as I mentioned earlier, often dangerous.

Nonetheless, from all I have heard, the company’s workers still considered a job at Weitz a big step up from sharecropping or tenant farming, which no doubt says a lot about what farming was like in that day, at least if you were African American and landless.

-3-

This is a photograph of a pair of the Weitz Veneer Co.’s workers in one of the company’s cutting rooms in 1938.

-4-

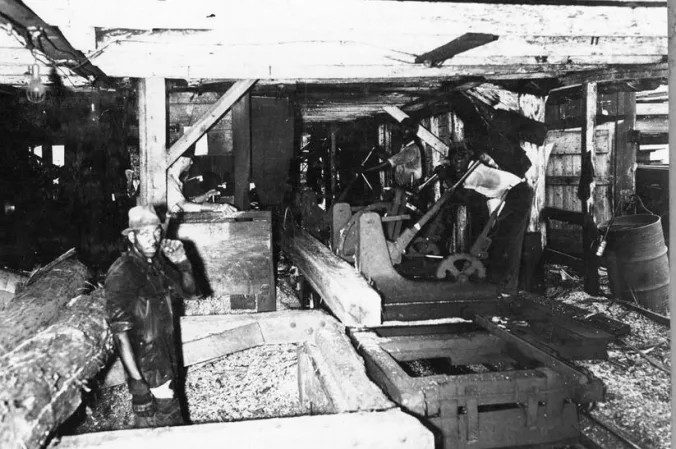

This is photograph from another company on the Roanoke, a sawmill in Williamston 20 miles upriver of Plymouth, in 1938. I am not sure, but I believe it is the sawmill at Saunders & Cox, a lumber company that had docks on the river a quarter mile east of the town’s U.S. 17 bridge.

If you look close, you will see at least four of the mill’s workers, and possibly a fifth back in the shadows.

The workers at Saunders & Cox received raw logs on the river and by truck. The logs could have been felled almost anywhere in the Roanoke River bottomland swamps or in the hinterlands– along the Cashie River or in the headwaters of the Pungo River, for instance.

Once the logs were sorted — “decking” in the trade — the sawyers went to work debarking and running the logs through the big saws. In most mills, they then ran the rough lumber through resaws or gang saws, capable of cutting multiple boards, that cut them into thinner boards.

The sawyers then used edging and trimming machines to shape the boards into four-sided lumber, after which the boards were ready for drying, which was sometimes done in kilns, sometimes in the open air.

-5-

This is another view of workers hoisting and debarking a log at the sawmill in Williamston, possibly Saunders & Cox, in 1938.

Judging from the company’s newspaper ads, this was not the kind of mill that shipped lumber far and wide. During the Great Depression, national demand for lumber plummeted and Saunders & Cox’s ads focused on local markets, mainly offering firewood and lumber for local building.

-6-

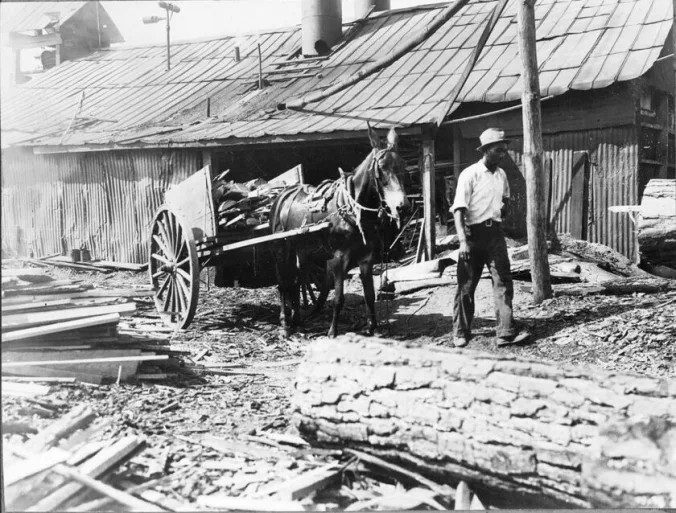

This is a our Williamston sawmill again, possibly Saunders & Cox, in August of 1938. A man leading a mule and cart through a lumber yard, or a field, was still a common sight in those last years before the Second World War, but that would not be true much longer.

Even in the 1920s and ’30s, mules, work horses, and oxen were everywhere. They pulled plows, hauled in fishing nets, dragged logs out of forests, and hauled wagons and carts laden with all manner of things.

But by the time that I was growing up in eastern North Carolina in the 1960s that had all changed.

I do not remember ever seeing a mule or any other work animal at a mill or factory.

At my grandmother’s little farm, we only knew one neighbor who still farmed with a mule in those days. He was a very endearing man, and very set in his ways, and so was his mule.

-7-

This photograph takes us back downriver to another wood products company that was located on the Roanoke River in 1938: the American Handle Co.’s factory in Plymouth.

The company was a division of the National Hoe Co., which was based in Cleveland, Ohio.

The National Hoe Co., in turn, was a subsidiary of the American Fork and Hoe Co., a sprawling near monopoly that had its roots in Vermont in the early 19th century.

At plants across the eastern U.S., the company’s workers made wooden handles for an astonishing array of farm, factory, and garden tools and equipment; purportedly more than a hundred types of shovel handles alone.

At the Plymouth plant, the company’s workers fashioned wooden handles for axes, hoes and other farm implements. I have often heard local people refer to the plant as the “ax factory.”

By most accounts, the workers made all of the handles out of white ash, which the company obtained from extensive forest holdings in Bertie, Washington, Martin and Halifax counties.

During and just after the Second World War, the company’s workers were part of a wave of union organizing that sought to improve pay and working conditions for mill workers along that part of the Roanoke and throughout much of eastern North Carolina.

-8-

Finally, we see a train load of logs rolling down the branch of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad between Plymouth and Williamston, 1938.

-End-

Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the state’s coast. More of his work can be found on his official website.