Note from the author: This is the first photo-essay in a series I’m calling “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.” You can find my introduction to the series here.

I want to begin this series by looking at a group of 21 photographs that chronicle threshing time on a peanut farm near Edenton in the years just before the Second World War.

Supporter Spotlight

The oldest of the photographs was taken in 1937. Others were taken in 1938 and in the autumn of 1941, just a few weeks before Pearl Harbor. One other was taken in 1942.

The first group of photographs focuses on the harvest workers, mostly the threshers, but also the diggers. A second group looks at the work of cleaning, grading and bagging the peanuts at a plant and warehouse in Edenton.

An ancient crop native to South America, peanuts spread across much of the world through the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the 16th and 17th centuries. Farmers in West Africa were among those who came to grow them.

Most historians and ethnobotanists believe that peanuts came to North America, especially to Virginia and North Carolina, via West Africa and the slave trade in the 18th century. By most accounts, they were long considered a crop mainly for feeding hogs and for feeding the enslaved Africans that were forced to raise crops on the region’s plantations.

According to a 2019 article in the journal Peanut Science, southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina were especially important in the crop’s early development in North America in large part because of the slave trade.

Supporter Spotlight

In the southeastern part of the North Carolina coast, the Wilmington area was also an important center of peanut farming in the the 18th century. Again, wholly reliant on slave labor.

By 1860, the majority of the peanuts in the U.S. were grown on North Carolina’s coastal plain, though they were rarely grown as a commercial crop.

Little is known about how enslaved people utilized peanuts as a food, though it is assumed that some of the traditional peanut dishes of the Gullah Geechee peoples date to the slavery era. A good description of peanut farming’s early history in the Wilmington vicinity can be found at the website for Poplar Grove Plantation, a historic site built around what used to be a slave labor camp in Pender County.

A number of factors contributed to making peanuts into a successful commercial crop in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Those factors included the adoption of peanuts as an easy-to-carry, nonperishable, high protein food by Civil War soldiers; the groundbreaking research that George Washington Carver did on new food uses for peanuts at Tuskegee Institute; and the collapse of cotton prices and the rise of the boll weevil in the 1920s, which led many southern farmers to search for alternative crops.

Another important factor in the growth of peanuts and peanut farming was the development of popular new peanut products.

Modern peanut butter was invented sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century, though there is some disagreement over where it was first made and who first invented it.

Another important development in the growing popularity of peanuts occurred in 1906, when two Italian immigrants, Amadeo Obici and Mario Peruzzi, both innovators in the roast peanut trade, established a partnership that led to the creation of the Planters Nut and Chocolate Co., which is still famous for its “Mr. Peanut” logo and mascot today.

When Obici and Peruzzi located their first plant in Suffolk, Virginia, 50 miles north of Edenton, in 1913, they guaranteed an almost endless demand for peanuts in the northeast corner of North Carolina, and other peanut processing companies followed.

Peanut candies were also growing popular in those first decades of the 20th century. The peanut-laden Baby Ruth candy bar first appeared in 1923, the no less peanutty Mr. Goodbar in 1925, Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups in 1928, Snickers in 1930, and Payday in 1932.

Cracker Jacks were a bit older — they were first developed in 1898 — but the popularity of Cracker Jacks and roasted peanuts soared with the popularity of baseball in the early 20th century.

All of which is to say, the demand for peanuts skyrocketed in the United States in the first half of the 20th century. Throughout that time, the center of the peanut farming and peanut processing industry continued to be southeast Virginia and northeast North Carolina.

When these photographs were taken in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the peanut belt in North Carolina ran from the counties on the north side of Albemarle Sound, including Chowan County, where Edenton is, west through Bertie, Martin, Northampton, and Halifax counties.

In those years, Enfield, a small town in Halifax County, was considered the state’s busiest peanut market.

In the photographs below, you will find something of a guide to this part of life and work in Eastern North Carolina’s history.

The photographs give us a glimpse at the people who worked in the peanut fields, and a look into a peanut mill in Edenton.

They introduce us to the kind of work that thousands upon thousands of mainly African American field workers did for much of the 20th century.

But as you will see, the stories behind the photographs also introduce us to people whom I never would have expected to meet in the peanut fields of Eastern North Carolina, including even Bahamian migrant laborers and Italian POWs from North Africa.

Note: I have arranged the photo-essays in my “Working Lives” series in chronological order to the extent possible. I’m beginning with these scenes from the peanut fields in Edenton because the earliest photograph among them is dated 1937. The last in the series will feature pickle factory workers in Faison and Mt. Olive in 1947.

So let’s get started with our first photograph, taken in the midst of threshing season on a peanut farm near Edenton.

-1-

In our first photograph, a broad view of threshing time on a peanut farm near Edenton is spread out before us. We can see a field that seems to go on forever, threshers at work, several mules, piles of peanut hay, the dust rising up off a mechanical peanut picker, and a pile of burlap bags heavy with peanuts.

Threshing was hard work, but the hardest work had already been done some weeks earlier, when scores of field workers had dug the peanut vines and pods out of the ground and set them out on stakes to cure.

Like beans and peas, peanuts are a legume, technically not a nut, but they are exceptional among the legumes because their pods develop beneath the ground.

To harvest the peanuts in this field, laborers, probably all of them African American, dug up the the whole plant: vine, pods and all. It was a grueling job accomplished with mules, plows, and a great deal of sweat.

After digging the vines out of the ground, the field workers shook the dirt loose from the plants before setting them out to cure. A task that, in my experience, is harder than it sounds and which nobody remembers fondly.

In a field this size, hundreds of field laborers would likely have done the digging, shaking and staking.

Firsthand accounts of peanut field workers’ labors are rare, but on July 5, 1983, the Wilmington Star-News ran an interview with an African American woman who dug peanuts on a large farm around the time that these photographs were taken.

The interview featured Ms. Carrie Simmons Ballard, who was born at Poplar Grove in Pender County in 1905.

The reporter wrote:

“As a child, she ‘put in many hours picking peanuts on The Big Lot’ where her great-grandmother was the main house servant for the Foy family. Her grandmother and mother also worked for the family. ‘They grew some cotton too, but the main farm product was peanuts,’ she said.

“‘I never did much cotton picking, but I sure did my share in the peanut fields…..’”

Ms. Ballard went on to say, “The thing that stands out most in my mind was how hard we worked for so little. It seemed like we had to work so hard for just some food and barely something to wear.”

-2-

In this photograph, we see what is apparently the same Edenton peanut farm, but three years earlier. In the foreground, we get an especially good look at the “shocks” that were typical of peanut farming in that day.

As field workers dug the peanut vines and pods out of the ground, they would place stakes in the ground and build up stacks of vines and pods around the stakes so that the pods could cure before threshing. Those mounds of peanut vines were called “shocks.”

Farmers typically left the shocks in the field and let the peanuts cure for five or six weeks before threshing began. To this day, some old-timers brook no doubt that peanuts cured in shocks are more flavorful than those cured in windrows, the more modern way.

-3-

This is another photograph of threshing time at the farm near Edenton.

In this case, we can see workers operating a mechanical thresher, usually called a picker, in the center of the photograph. However, I was really drawn to this photograph because it highlights the peanut shocks stretched out in the field behind the threshers.

A field full of peanut shocks was a sight to see, reflecting endless hours of toil. In the largest fields, such as this one, they always remind me of the scenes in “Anna Karenina” of threshing time in the Russian countryside.

-4-

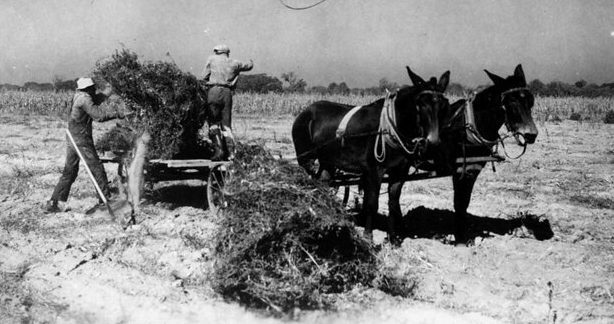

After the peanuts had cured, farm workers pulled up the stakes and raked up the hay, as it was called, being careful to stay clear of the snakes and rats that were notoriously fond of them.

Horses or mules would then cart the hay to a stationary mechanical picker that operated in the field.

The 1940s was a moment in history when tractors and mules often worked side by side in Eastern North Carolina’s fields.

Even as late as 1940, only about 4% of the state’s farmers owned tractors. Even a large, comparatively prosperous farmer, as the owner of his field must have been, was unlikely to have more than the one tractor, which, as we will see, this farmer was using to power his mechanical picker.

The end of the Age of Mules was nigh, but it had not yet arrived on the eve of the Second World War.

-5-

Here we see workers unloading hay next to the mechanical picker in our peanut field outside Edenton.

On the right, we can see a pile of stakes that have already been stripped of their vines. On the left, a man is stitching up a burlap bag of peanuts that have just come out of the picker.

-6-

By the time this photograph was taken, at least larger peanut farmers were using pickers such as this one that were powered by long belts attached to the back axel of a farm truck or, in this case, a tractor.

Even a few years earlier, horses or mules would have done the job.

-7-

This photograph provides a closer look at the farm’s mechanical peanut picker, a machine that was designed to break up the hay, remove the peanuts from the vines, and shake out debris and dust. It was a technology that had just come into widespread use in the previous two decades.

An unschooled African American farmer and inventor named Benjamin Hicks, in Southampton County, Virginia, filed what is believed to be the first patent for a mechanical peanut picker in 1901.

By all accounts, Hicks cobbled his ingenious machine together with a blacksmith’s anvil, tool box, and carpenter’s tools.

At least two makers of farm equipment modeled their peanut pickers on Hicks’ design, one of them without his consent.

To learn more about that patent dispute and about Benjamin Hicks, see Anna Zeide’s recent article in the journal Agricultural History, “The Dignity of Invention: Race, Intellectual Property, and Peanut Agriculture, 1900-1920.”

-8-

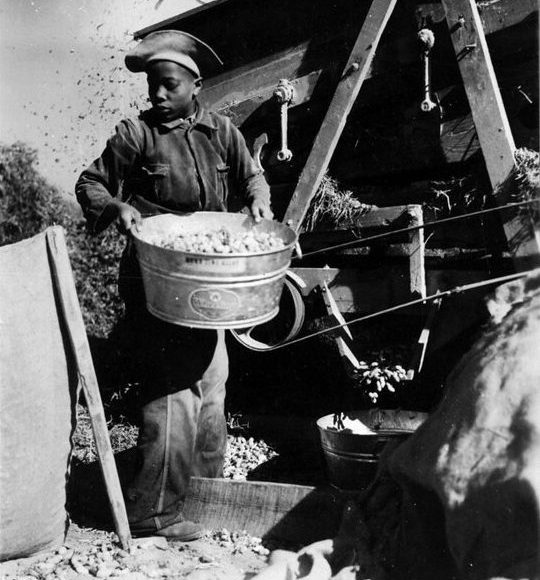

In this photograph, we see one of the many young field workers that labored in this farm’s fields during the peanut harvest.

The mechanical thresher separated out the peanuts, emptying them into galvanized tin tubs. This worker is carrying the nuts to other field hands who will bag them, stitch the bag shut, and load the bags onto a truck.

At that time, the average wage for agricultural workers on the East Coast of the U.S. was $1.20 a day.

As part of the New Deal, President Franklin Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress had enacted important child labor reforms during the Great Depression. Those laws specifically exempted children who worked on farms.

By one estimate, half a million children were working in America’s fields in 1938.

-9-

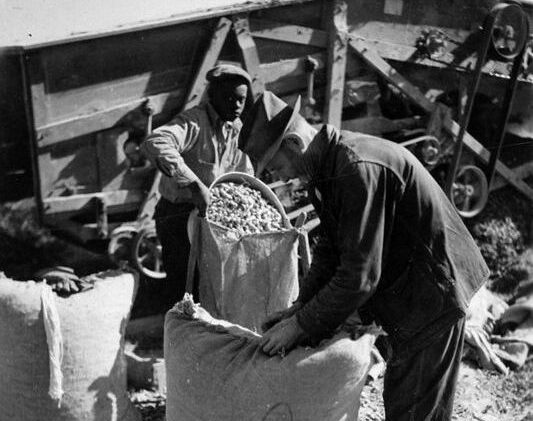

In this photograph, we see another young field worker emptying a pail of peanuts into a burlap bag, while another, older man stitches a bag shut and makes it ready for shipment.

-10-

The farm workers next loaded the bags of peanuts onto a truck that would carry them into one of the two peanut processing plants in Edenton.

Note the sea of peanut shocks in the distance. They seem to go on forever.

On the upper left, we can see the dust rising up from the mechanical picker as it separates the vines and peanuts.

-11-

Once the peanuts had been separated, laborers carted away the peanut hay usually for use as livestock feed.

Farmers valued peanut hay as an especially good feed for hogs.

-12-

I am not exactly sure what is happening in this scene, but I suspect that we are looking at a small hay baler or a presser that flattened and compacted the vines after they passed through the picker. Farmers sometimes used such machines to make it easier to store the hay for use as livestock fodder.

-13-

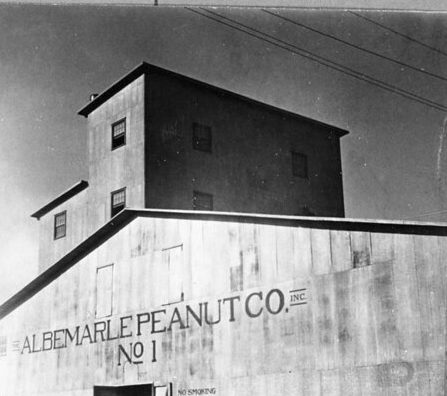

A large part of the peanuts harvested on that north side of the Albemarle Sound ended up here, at the Albemarle Peanut Co.’s plant in Edenton. Located on a bay that is on the north side of Albemarle Sound, Edenton is the county seat of Chowan County, and at that time had a population of just under 4,000 citizens.

At the time these photographs were taken, Edenton was home to two peanut processing plants, the Albemarle Peanut Co. and the Edenton Peanut Co.

By 1935, according to the Greensboro News & Record on Aug. 16, 1935, the two companies were handling a total of some 25,000,000 pounds of peanuts a year.

The plant’s workers shelled, cleaned and bagged peanuts for farmers near Edenton and the rest of Chowan County, as well as peanuts harvested from farms in surrounding counties.

According to a number of accounts, you could tell when the plant was operating from some distance because a haze of smoke blanketed North Edenton when the plant was fueling its boilers with discarded peanut shells.

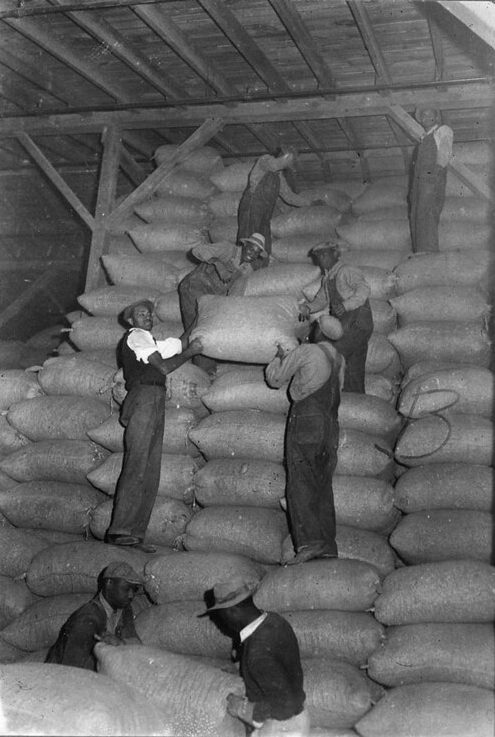

-14-

Here we see a great pile of peanuts waiting to be cleaned and graded at the Albemarle Peanut Co.

These workers are stacking freshly arrived, 100-pound bags of peanuts, still in the shell, in the company’s warehouse.

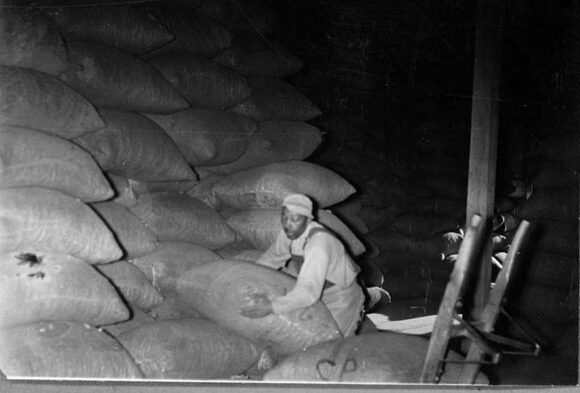

-15-

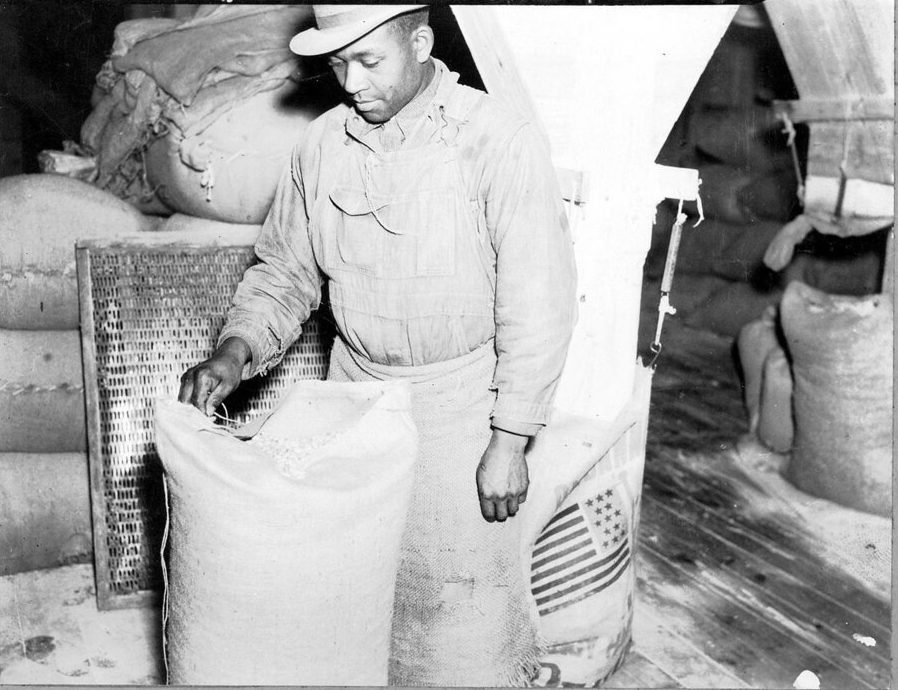

In this photograph, we see one of the Albemarle Peanut Co.’s hands lifting a bag of unshelled peanuts at the company’s warehouse.

He may be adding the bag to the stockpile or he may be taking the bag off the pile and loading it onto the handcart on the right so that he can carry it into the mill’s shelling and cleaning rooms.

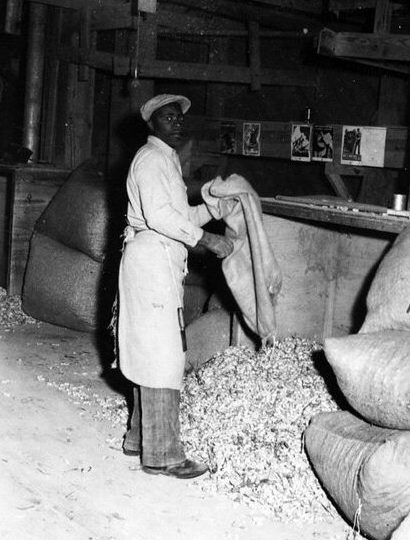

-16-

This gentleman is emptying bags of peanuts so that they can be placed on conveyor belts for cleaning and grading.

Like many of the other photographs of peanut farming and peanut processing in the state-managed collection, this photograph was taken in 1941, quite likely just a few weeks or even days before Pearl Harbor.

Long before that time though, U.S. war planners had begun planning how to adjust the nation’s crop production to compensate for expected wartime disruptions in the agricultural supply chain.

They did so with an eye both toward meeting the country’s domestic food needs and toward fulfilling the country’s Lend-Lease Act agreements with Great Britain and other allied countries.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, the war cut off 68% of the nation’s supply of imported vegetable oils within a year of this photograph.

That was an issue of concern to American consumers, but in some cases it was also a concern for the U.S. military.

Just to cite one example, the bulk of the palm oil used in the United States to produce nitroglycerine for military uses had come from the Philippines prior to the beginning of World War II.

However, that supply of palm oil was completely cut off when Japan occupied the the Philippines in May 1942.

Looking for substitutes for imported oils, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Monthly Review July 31, 1942, noted, “a widespread program was launched, calling for increases in production of lard, tallow, cottonseed oil, peanut oil, soy beans, and other fats and oils.”

The article goes on to say, “Farmers in the South. . . are taking an important part in this program by expanding the production of peanuts.”

At the time this photograph was taken, military planners had just announced a federal program to expand the country’s peanut acreage by 83 percent, roughly half of which would be set aside for use as oil.

Later in the war, the government would push to raise the country’s peanuts acreage by another 50%, all of which left peanut farmers and the workers at the Albemarle Peanut Co. with little time to rest.

As part of the wartime effort to increase peanut production, the USDA even arranged to rent mechanical pickers and threshers to farmers at a low fee in order help them increase peanut acreage.

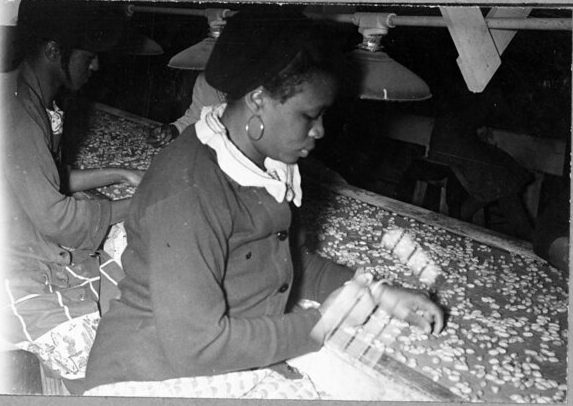

-17-

Here we see young women removing flawed or shriveled peanuts from a conveyor belt at the Albemarle Peanut Co.

-18-

This is a view of some of the chain belts that powered the conveyors at the Albemarle Peanut Co.

-19-

During the Great Depression, times were hard in Edenton, as they were throughout most of the North Carolina coast.

Somewhere between a quarter and a half of the town’s citizens were on some kind of public relief. Unemployment rose above 25%. Few could afford doctors or medicines. In many homes, mothers and fathers struggled to keep food on the table. Many cut back, trying to get by on one meal a day.

Far too many grew far too acquainted with hunger and malnutrition.

Against that background, the success of the two local peanut plants — no matter how hard the work, no matter how poorly it paid — was one of the few bright spots in Edenton’s business scene.

In the words of the Raleigh News & Observer Jan. 19, 1933, the two plants were “a great help to the destitute condition of many Edenton families.”

Between them, the Albemarle Peanut Co. and the Edenton Peanut Co. employed some 150 to 200 workers in season and the peanut industry overall was one of the town’s largest employers.

In this photograph, one of the Albemarle Peanut Co.’s workers is sewing up burlap bags of peanuts to prepare them for shipment.

This photograph appeared to be dated 1938 in the collection at the State Archives. However, I realized it was actually taken a year earlier, in the fall of 1937, when I found a copy of it printed in a horribly racist article on Edenton’s peanut industry that appeared in Raleigh’s News & Observer on Nov. 14 1937. I knew of course that the N&O had been a self-proclaimed champion of “white supremacy” in the late 19th century and in the early part of the 20th century. For me, that 1937 article was a poignant reminder of how long the newspaper remained true to its roots.

-20-

In this photograph, we see one of the Albemarle Peanut Co.’s workers carting bags of peanuts out to the plant’s loading dock.

Looking back now, the transformation of Eastern North Carolina’s economy that occurred in the scant few years between the earliest photograph in this group– during the Great Depression in 1937– and the last, on the eve of World War II, was almost breathtaking.

As the nation prepared for war, massive federal investments in the construction of military installations, defense industries, and shipyards especially on the North Carolina coast– and a tremendous infusion of federal dollars into supporting agriculture– proved to be a life-changing moment for countless families and for the future of the region.

During the Great Depression, incredibly high unemployment and the collapse of crop prices had been devastating for Eastern North Carolina.

That all changed during the war. By 1943, the War Department had actually declared the whole region to be a “labor shortage zone,” a designation that meant that the federal government should not target the area for other military projects out of concern that there might not be an adequate supply of civilian labor to build or support them.

Even as early as 1941, when many of these photographs were taken, a general shortage of rural labor was being felt throughout Eastern North Carolina, and the federal government’s push for increasing peanut acreage was one of many special challenges.

To address that wartime labor shortage– and regrettably, also to resist demands from African American workers to raise wages and improve working conditions– peanut farmers in northeastern North Carolina often turned to migrant farm workers and to German and Italian POWs.

In 1943, for example, the War Manpower Commission recommended that 1,500 POWs be sent to northeastern North Carolina for the peanut harvest. Five hundred Italian POWs were assigned just to the peanut harvest in Bertie, Hertford, and Martin counties.

That same year, a temporary camp for Italian POWS was erected at a baseball field in Tarboro, in Edgecombe County, just to supply labor for the local peanut harvest.

An article in the Durham Herald-Sun indicated that the Italian POWs at the Tarboro camp were mainly from Sicily and from Italy’s colonies in North Africa – so they may have included men from what are now Libya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and/or Somalia.

The next year, 1944, state records indicated that POWs alone harvested a total of 9,141 acres of peanuts in Eastern North Carolina. Asheville Citizen Times, Feb. 22, 1945.

For most of the war, the Farm Security Administration, or FSA, also directed migrant laborers to the region’s peanut fields.

In the fall of 1943, the FSA even opened a special government-run migrant labor camp in Enfield, in Halifax County, to house 400-500 peanut harvest workers.

Even as late as the fall of 1945, after the war was over, state and federal manpower agencies diverted hundreds of Bahamian laborers to northeastern North Carolina’s peanut fields.

That year the short-lived Naval Air Station in Edenton also temporarily housed POWs. They were only there during the peanut harvest, then returned to a POW camp in Ahoskie. Salisbury Post, Sept. 4, 1945.

-21-

These may be bags of unshelled peanuts waiting to be carried into the Albemarle Peanut Co.’s plant or they may be bags of processed peanuts waiting to be trucked out or shipped out by railroad.

In that day, a large percentage of the South’s peanut crop as a whole was bound for oil mills and peanut butter factories. Some of the peanuts that came through the Albemarle Peanut Co. no doubt had the same destination.

That said, compared to peanut varieties grown elsewhere, there was an especially high demand for the “Virginia style” peanut variety that was most commonly grown in Tidewater Virginia and in northeastern North Carolina for use as “cocktail peanuts” and for roasting.

In those last days before the war, there was really no telling where these peanuts were bound. Some of them may even have ended up on foreign battlefields, either in the packs of American soldiers or those of soldiers from Great Britain, the Soviet Union, or one of our other allies.

Acknowledgements

I want to extend a special thanks to the USDA’s James Davis III for helping me to interpret the scenes in these photographs. A third-generation peanut farmer in Palmyra, N.C., Mr. Davis was North Carolina’s “Small Farmer of the Year” in 2002 and is now a chief program officer at the USDA’s office in Raleigh.

Mr. Davis told me that some of his knowledge of peanut farming came from his farming days, some from his studies at N.C. A&T, and some from his long years as a county farm agent and director of the USDA’s office in Halifax County, N.C.

Above all, he told me, his most important teachers were his father and grandfather, the latter of whom grew up sharecropping in Edgecombe County, N.C., and ended up buying and operating his own farm in Palmyra just after the Second World War.

I am very grateful for his assistance, and I hope very much that I did justice to his lessons.

Thank you too to Professor Katherine Charron at N.C. State University and the Grant family in Tillery for introducing me to Mr. Davis.

Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the state’s coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.