It was the massive scale of destruction in the North Carolina mountains after Hurricane Helene last year that spotlighted how advantageous microgrids — small independent power grids — can be to communities that have suffered disasters.

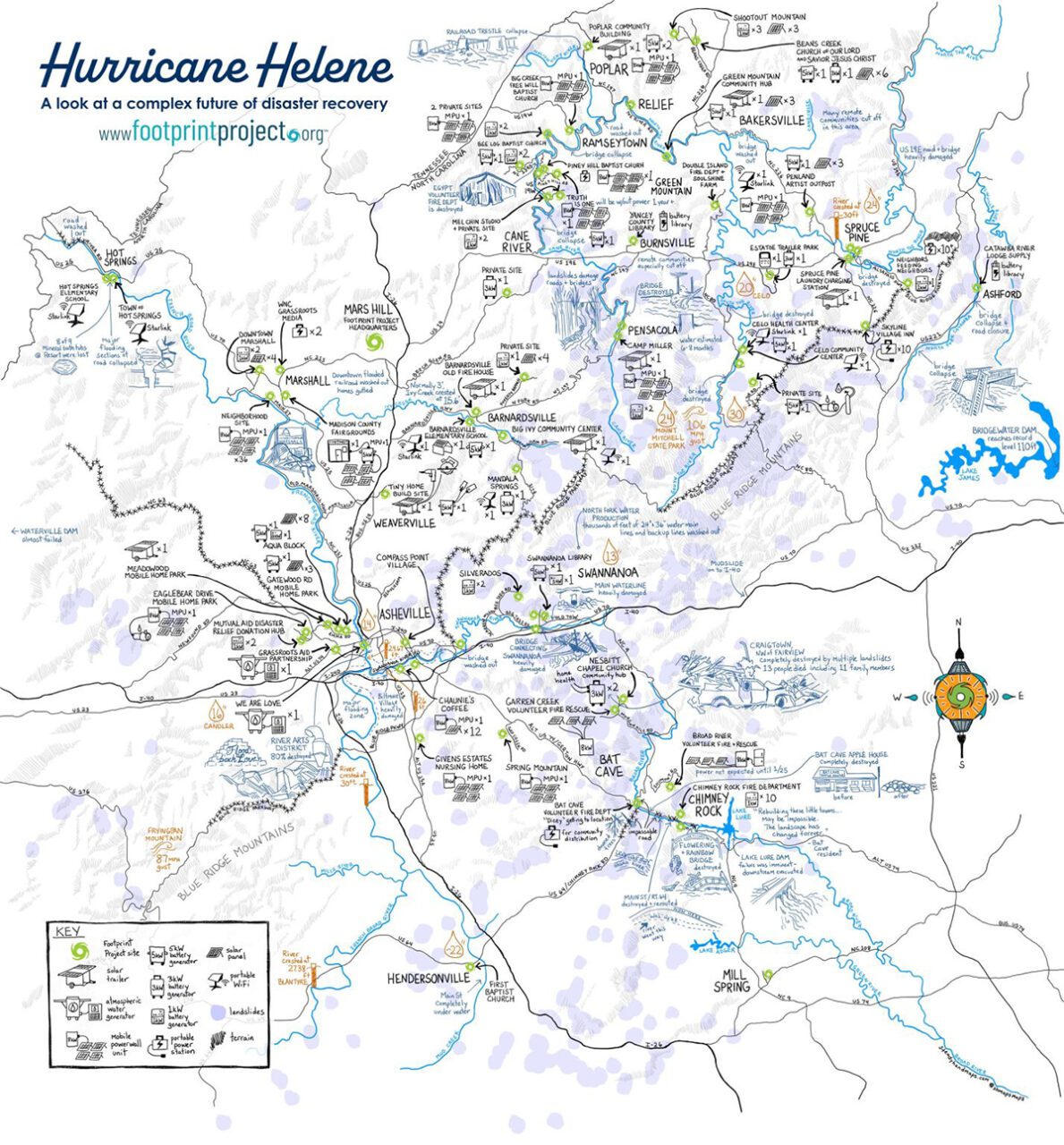

After horrific flash floods from the storm that hit Sept. 27 inundated many of Asheville’s roads and buildings — and nearly all of its vital utility infrastructure — critical help soon arrived from the New Orleans-based nonprofit disaster service Footprint Project in the form of mobile renewable power.

Supporter Spotlight

An estimated 1 million western North Carolinians lost power in the storm. Many were also left without running water, food and shelter.

“We saw the value in what they were doing, in deploying small-scale solar and battery storage to help communities that lacked access to power, water and telecommunications,” North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association Executive Director Matt Abele told Coastal Review. “And so we jumped in right away and helped to fundraise for them to be able to expand the amount of work that they were doing in that part of the state.”

Apparently, the practicality and flexibility of the technology also impressed officials with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality State Energy Office, which on Aug. 12 announced a $5 million investment to provide accessible post-disaster emergency power with permanent and mobile microgrids.

“Hurricane Helene showed us that we need to be prepared to withstand severe weather emergencies,” Gov. Josh Stein said in a press release announcing the plan. “That means rebuilding our energy infrastructure with resilience in mind.”

Along with NCSEA and the Footprint Project, the state energy office will collaborate in the project with Land of Sky Regional Council, as well as a network of regional partners.

Supporter Spotlight

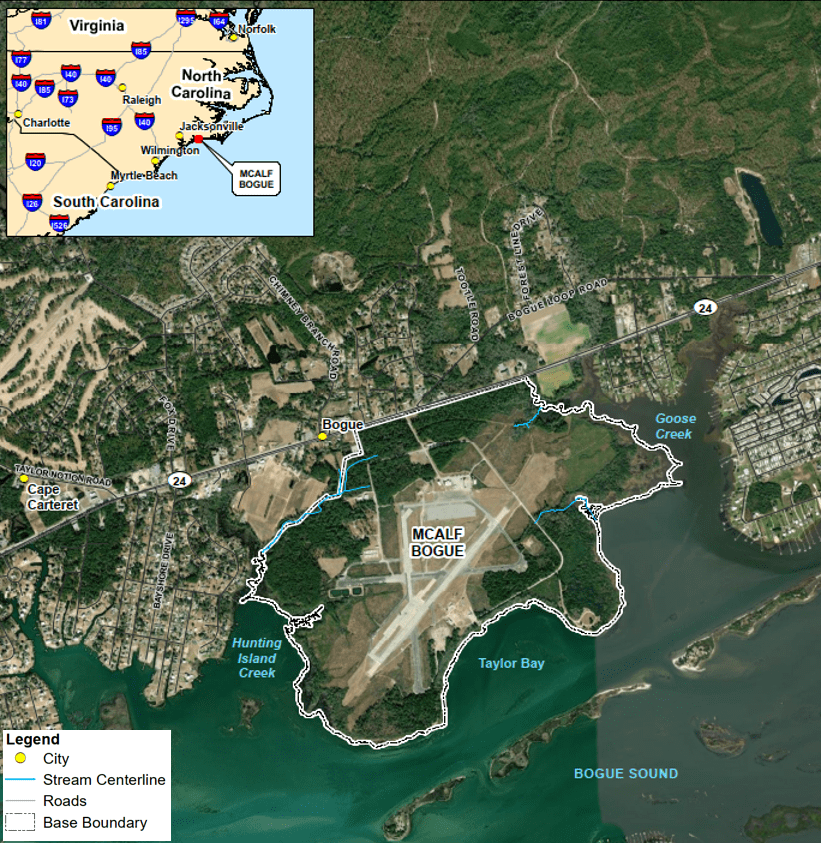

With as many as 24 stationary microgrids that would be installed across six western counties affected by Helene and two mobile Beehive microgrid hubs, one on the coast, the other in the mountains, the project is intended to fill critical needs in communities statewide.

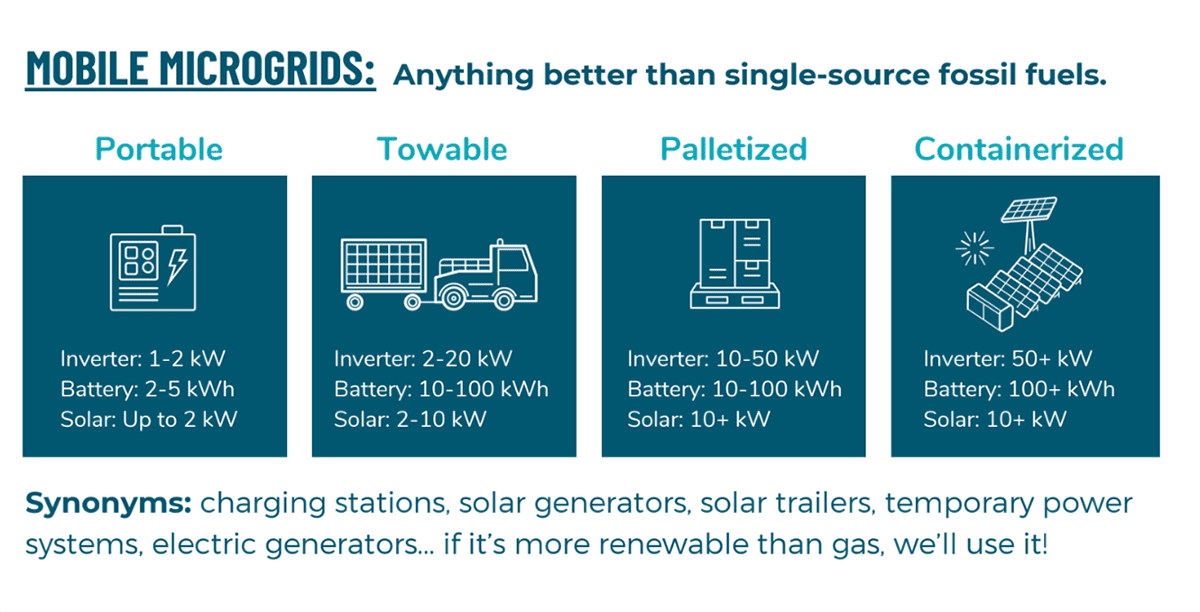

Essentially four large shipping containers with solar panels on top of the outside and battery storage systems inside, each Beehive — the “Hive” — operates independent of the stationary power grid. Smaller mobile solar-equipped trailers — the “Bees” — are dispatched to affected areas to provide power for essential services such as water filtration stations, charging stations for phones and other devices and hotspots for internet through cellular or satellite connections.

Abele said that NCSEA became familiar with Footprint through its relationship with Green Tech Renewables, a nationwide distributor of solar and battery storage that had partnered with the Hawaii Solar Energy Association and Footprint in responding to Maui wildfires.

Abele said his organization reached out via email to Footprint as Helene was approaching the mountains. As it turned out, the large scale of the damage and the randomness of impacts from the storm really highlighted the value of the Beehives being able to go where needed.

“I think that’s the beauty of having a setup like these Beehive microgrids, where you can charge mobile equipment,” Abele said. “Because only investing in permanent infrastructure, it’s like trying to essentially find a needle in a haystack and predict exactly where the next storm is going to hit, versus having the equipment on hand and ready to go, to be deployed to where that next storm is.”

Green Tech’s Raleigh location had solicited donations of solar panels and other supplies, as well as raised funds to purchase products such as photovoltaic wire and batteries, and trucked it to western North Carolina to support Footprint Project’s work, as described in an article published by Elizabeth Ouzts for the nonprofit news site Energy News Network in October 2024.

According to the article, by late December the group had built about 50 microgrids throughout mountain communities. That was the most ever since it started in 2018 in response to founder Will Heegaard’s experience two years earlier working as a paramedic in New Guinea and struggling to find power to refrigerate blood supplies.

Heegaard, today operations director for the Footprint Project, which he founded with partners Jamie Swezey and Nate Heegaard, said the group is working toward replacing the fossil-fuel-powered generators that have long been serving communities after disasters with battery-charged solar panels. Not only are Beehives and Bees not dependent on fuel supplies, they’re quiet and clean.

“Responders use what they know works, and our job is to get them stuff that works better than single-use fossil fuels do,” he told Energy News Network. “And then, they can start asking for that. It trickles up to a systems change.”

Even if the microgrids don’t outright replace those generators, Heegaard added, they can supplement them, helping fuel supplies last longer.

The state’s grant will provide about two beehives with mobile equipment and permanent installations with fixed solar and battery storage that would be attached to either local government buildings or nonprofit center or other location where people congregate after a storm, Abele said.

“And so those are all really important decisions in terms of where that investment is being made, to ensure that it is being made in a place that people will go and serve the community appropriately,” he said.

“Because the worst-case scenario is, you walk down a path of investing, and then deploying infrastructure, and then that infrastructure sits unutilized during a natural disaster because it’s inaccessible,” he said.

According to the state, the Land of Sky Regional Council, part of the Appalachian Regional Commission, will soon begin purchasing the Beehive microgrids, and site selection for the microgrids is to begin this fall. The stakeholder engagement for the installation will take place in September, and project completion is anticipated in June 2027.

One of the most significant reasons that solar-powered microgrids like the Beehive hadn’t found much traction in the U.S. is because of the high cost of batteries, Abele explained. But now, he said, the price of batteries — similar to what happened earlier to solar panels — has decreased about 92% in the last 15 years, making the much-improved technology affordable.

“We’ve seen sort of a smattering of these projects on an ad hoc basis, but not a comprehensive strategy around deploying this equipment,” he said.

In addition to the proposed Beehives, there have been other smaller microgrid projects in the state, including on Ocracoke and plans in Charlotte.

“But aside from that, there aren’t a ton of examples that you can point to in other states,” Abele said. “And so I think North Carolina really is going to be a leader in setting the example for recovery after a natural disaster.”