Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the state’s coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

Today I would like to introduce a series of photo-essays that I will be publishing here over the next few weeks. Each of the photo-essays — some very brief, some longer — will focus on the working lives of people in eastern North Carolina just before, during, and after the Second World War.

Supporter Spotlight

The longest of the photo-essays features 22 historical photographs. In the shortest ones, though, I will try to build a story around a much smaller group of photographs, and sometimes only a single picture.

In all cases, I have based my stories on photographs that are part of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development Collection at the State Archives in Raleigh.

Between 1937 and 1951, the department photographers created a collective portrait of the state’s farms, industries, and working people. Some of the photographs were used in state publications or shared with magazines and newspapers. The vast majority, though, have not appeared in print.

Few of the photographs have the kind of artistic qualities that we see in the classic tradition of American documentary photography. For example, in the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, photographs of life in America during the Great Depression.

Nonetheless, I find something extremely compelling about them. Perhaps above all, I am drawn to the way that the photographs take us into fields and factories that are rarely if ever included in the stories that we historians tell about the history of North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

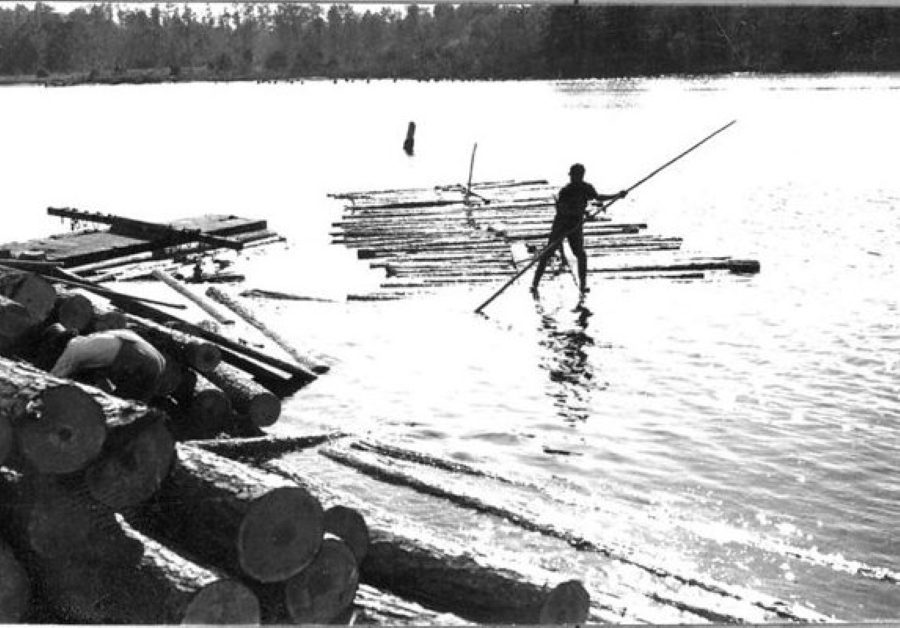

They are not romanticized images of working people. They are more matter of fact, more hard nosed and grittier.

These are images from down by the railroad tracks. From the warehouse district. From the engine room.

From the fields. From the lumberyards. From the textile mills. In one case, even from an actor’s makeup room.

In many of them, you can feel how hot it was, or how cold, the strain of the long days, the dangers that the people in them stood up to, all for the sake of making a living and looking after their families.

In some, you can see the pride that the people in these photographs took in their toil and craftsmanship. In others, you look at the people’s faces and wonder how they kept going.

The photographs that I am featuring are only a very small portion of the historical photographs in the Department of Conservation and Development Collection.

I have chosen to sort them into nearly 20 photo-essays featuring a total of 100 photographs in all.

The photographs that I have chosen were all taken in eastern North Carolina, basically east of I-95 today. Some were taken quite close to where I grew up on the North Carolina coast, a few even look at a sweet potato harvest on my great-uncle’s farm in Carteret County.

Others take us into different fields and factories, mills and migrant camps, remote fishing camps and distant seas.

My choice of photographs may seem eclectic at times. But I picked each photograph, or group of photographs, because I thought that they offered a special window into some important aspect of the history of eastern North Carolina, and because I thought that they led us to interesting stories.

I hope you enjoy all of the photo-essays. I will begin the series sometime in the next few days with the longest, which focuses on photographs of threshers in peanut fields near Edenton, at the end of the Great Depression and in the days just before the Second World War.

Even in that very provincial sounding subject — threshers on a peanut farm — I think you may be surprised where the story leads.

As I worked my way through the photographs from that long ago peanut farm, I was introduced to a host of unexpected stories and working people. Just in those few handfuls of photographs, you will meet Bahamian migrant laborers, POWs from North Africa, a pioneering black inventor from Southampton County, Virginia, and Mr. Peanut, among others.

You may also learn, at least I hope you will, a surprising amount about peanuts, the history of peanut farming, the evolution of farm labor and farm machinery, and the national security crisis that led to the dramatic expansion of peanut farming during the Second World War.

To say nothing of plenty of fun facts about the invention of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and Baby Ruths.

Above all, and all kidding aside, I hope that these stories will help you to look at these men and women, and sometimes mere children, with a sense of kinship, a feeling of brotherhood and sisterhood.

Next in the series: “In the Peanut Fields of Edenton, 1937-41”