The Outer Banks are known for vast, uncrowded beaches, towering lighthouses, and unique cottages, and while these features beckon millions of visitors, some Outer Banks communities are not as well-known.

Rather than towns, most communities here are unincorporated villages, each home to residential homes and unobtrusive tourist accommodations, a few businesses, and a post office. Hatteras may be one of the best known of these villages.

Supporter Spotlight

While it is much smaller than incorporated coastal towns like Beaufort or Edenton, Hatteras is home to centuries of history and a number of notable sites, particularly on the southwest tip of its namesake island.

Hatteras Island was populated in the 16th century by the Croatoan Native Americans. They hunted, fished and ate oysters, depositing the shells in massive middens that are one of the few remaining visible indicators of where they lived. They were one of the many Native peoples that the Roanoke Colony interacted with in the 1580s.

The Croatans allied with the Europeans and counted among their numbers Manteo, the first Native American christened by the English in the New World. They factor into the story of the Lost Colony, since Hatteras Island was one of the many areas where the colonists were rumored to have gone after leaving Roanoke. Due to the shifting sands of Hatteras and the lack of definitive records, the fate of the colonists remains a mystery to this day.

Europeans returned to the area in the middle of the 17th century. Historian David Stick notes in his book, “The Outer Banks of North Carolina,” that the first documented English settlers on Hatteras Banks, Patrick Mackuen and William Reed, likely arrived there by 1711. People on Hatteras lived by fishing, farming, and piloting boats. They also took cargo from the many shipwrecks that regularly washed ashore from the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

Despite a growing number of families living on Hatteras, the area was slow to develop as a proper town. Isolated and accessible only by water, Hatteras did not abut one of the major inlets that was open during the colonial period. As a result, it was ignored by the same legislative assemblies that facilitated town construction at nearby Portsmouth and Ocracoke islands. Although numerous people resided on the southwestern portion of the island by the late 18th century, colonial maps often showed just the empty banks and the cape. The area known today as Hatteras Village finally gained its first post office in 1858.

Supporter Spotlight

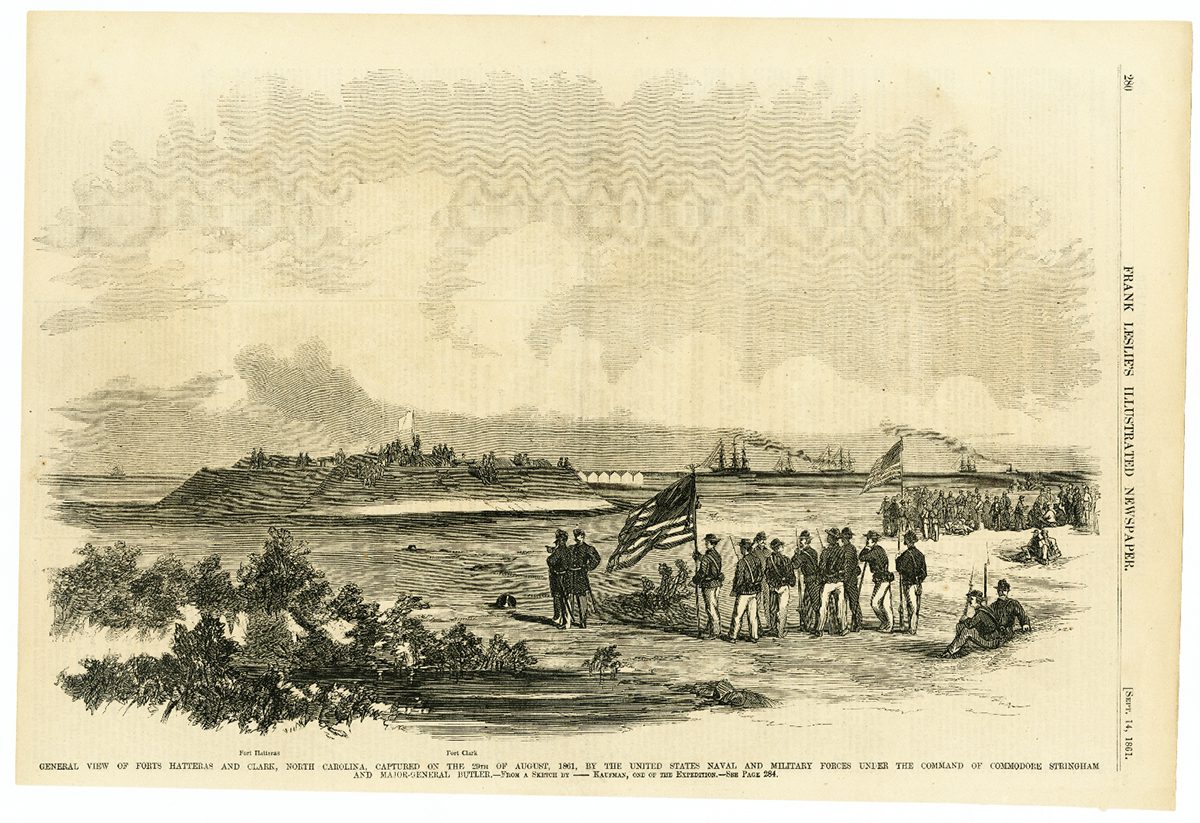

Hatteras remained mostly isolated through the 18th and early 19th centuries. But while it did not have obvious economic importance, it did have military significance to any group wanting to approach or protect North Carolina by water. This led to the construction of Confederate forts Hatteras and Clark on Hatteras Inlet in 1861.

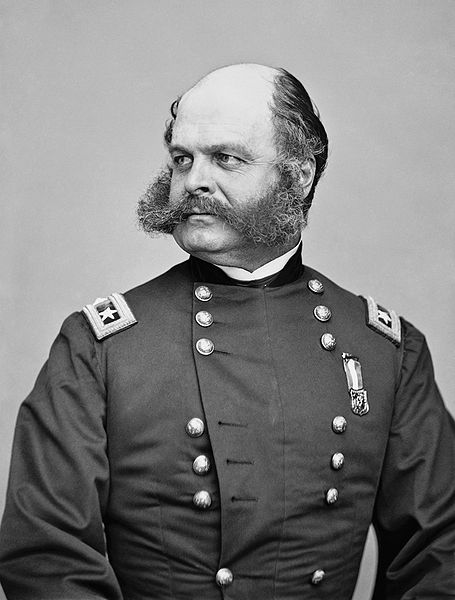

The forts were surrendered to Union in the first combined action of the Army and Navy during the Civil War. This success, the first by Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside, helped the Union gain control of the North Carolina coast and allowed for future invasions of Roanoke Island and the eastern part of the state.

The post-Civil War period saw the emergence of coastal life-saving stations. These buildings housed crews organized to rescue victims from shipwrecks using the latest technology, such as the Lyle gun used to shoot rescue lines.

Three U.S. Life-saving Service stations lined Hatteras Island by 1905, from Durants near the village to Cape Hatteras at the eastern end of the island. Along with greater lifesaving capabilities came a new effort at political organization. Dare County, one of the last counties formed in North Carolina, was created in 1870 from what had been parts of Currituck, Hyde and Tyrrell counties to help administer the far-flung islands of the Outer Banks. Its southern boundary was the western tip of Hatteras Island.

The modern village of Hatteras began to develop in the early 20th century. Locals built a string of houses such as the Ellsworth and Lovie Ballance House, circa 1915, one of the oldest structures in the village and a survivor of numerous hurricanes over the past century, according to state historic preservation records. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.

Growth came mainly from tourism. Greater rail and automobile transportation helped more and more visitors reach the beach from such areas as Raleigh, Charlotte and northern cities. More tourists meant an increase in ferry traffic and the growth of roads that made those ferries accessible, such as the highway that became U.S. 264 connecting Belhaven, Swan Quarter and U.S. Highway 64 near Manns Harbor.

In the 1930s, the conservation movement also brought nature tourism to the island through the authorization of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore in 1937, one of the first seashore-protection programs in the country. Conservation protected a unique ecosystem that continues to bring thousands of birding, fishing, and native plant enthusiasts each year.

With these dynamics in place, Hatteras became a popular vacation destination. Thousands flocked to the coast every summer and engaged in new recreational activities such as surfing and kiteboarding. Demand led to new transportation outlets. The state began to pave roads on Hatteras Island in the 1950s, but it was the completion of the Herbert S. Bonner Bridge in 1963 that provided a direct land connection between Hatteras and the rest of the country.

Soon, the island became home to shops, restaurants and hotels, as well as the familiar fishing shacks and isolated tourist cottages. A 1990 New York Times travel article that praised Hatteras Island’s beach as “one of the loveliest on the East Coast,” also singled out the village for offering “the color of a commercial fishing hub.”

Hatteras has become one of the most popular tourist destinations on the East Coast, growth that has fundamentally altered life in the sleepy fishing village. About 500 residents now live in Hatteras Village fulltime. There are about a dozen restaurants, several seafood markets, general stores, visitor centers, and the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum. A number of these businesses operate year-round and cater to both locals and the summer influx of tourists.

Despite these changes, residents largely are thankful that Hatteras retains much of its village charm.

Patricia Peele, a lifelong resident of the island, told Coastal Review that as recently as 15 years ago, it was like “they used to roll the streets up at 9 p.m. on Labor Day.”

Now, there are always tourists, filling a plethora of mini-hotels across the island. But Peele said that despite the changes, she knows that Hatteras is still secluded compared to the rest of the Outer Banks. It is “not built up like a lot of other places are,” and with the protections provided by the National Park Service, growth will likely remain limited.

Still, Hatteras Village faces many of the same challenges as the rest of the Outer Banks, including those related to rising sea levels, limited resources and strong coastal storms.

The Basnight Bridge, which replaced the Bonner Bridge when the 2.8-mile, $254 million project was completed in 2019, keeps Hatteras Island connected to the mainland, and no matter the challenges, people of Hatteras will likely continue to adapt to life on their ocean sandbar — just as they always have.