Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the state’s coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

As I looked through an extraordinary group of historical photographs at the State Archives in Raleigh, I found a group of old photographs taken during the Second World War that surprised me.

Supporter Spotlight

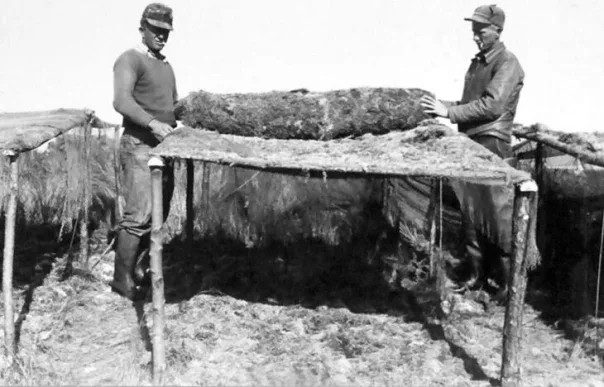

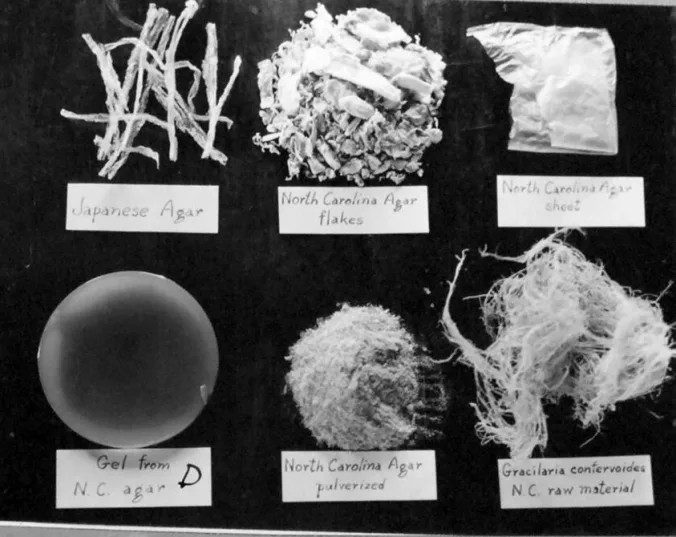

Some of the photographs show local fishermen harvesting seaweed in the waters off Beaufort in the summer of 1944. Others show the inner workings of a factory in Beaufort that was established during the war to process that seaweed into a jelly-like substance called agar.

Produced by extracting polysaccharides from the cell walls of certain species of seaweed in the red algae family (Rhodophyta), agar has dozens of uses today.

Many of them are culinary. Others have to do with the pharmaceutical industry, medical research, and health care.

Agar is even used in the textile industry, food preservation, and brewing.

However, if you are like me, you remember agar for just one of those uses. Like medical researchers and basic scientists around the world, my high school biology teachers used agar as a growth medium for bacteria. The translucent gel that lined the bottom of our petri dishes was agar.

Supporter Spotlight

By using agar, we could grow bacterial cultures on our own, and our teachers could help us to understand the basic properties of bacteria, one of the most ubiquitous forms of life on Earth.

In those petri dishes, that thin layer of agar served as a solid, stable, and nutritious surface for the bacteria to grow, and one that would not be eaten up by the bacteria before we could plumb its secrets.

In the photographer’s notes on the agar factory in Beaufort, I was also surprised to see repeated references to Pivers Island, the small island that is just across the channel from Beaufort and is home to the Duke University Marine Laboratory and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Beaufort laboratory.

The notes were rather obscure, but they made clear that scientists on Pivers Island at the Duke marine lab and at the U.S. Government Fisheries Laboratory, a predecessor of NOAA, or both had played a central role in the establishment of the agar factory in Beaufort.

I felt a little chastened that I had not previously heard a single word about the agar industry in Beaufort or Pivers Island.

I grew up only 20 miles from both Beaufort and Pivers Island. I even lived on the Pivers Island for four months back in 1981, when I was a student at the Duke marine lab. I was a history and botany double major at Duke.

My mother even went to school on Pivers Island during the Second World War. She grew up out in a rural part of Carteret County, but she attended Beaufort High School during the Second World War.

She was a senior when the school burned down over the Christmas holidays in 1944.

My mother’s class finished its senior year on Pivers Island. Her classes met in buildings that were usually used by the marine lab’s summer students.

On several occasions, I have done historical research in two libraries on Pivers Island: the Pearse Memorial Library at the Duke Lab and the library next door at what is now called the NCCOS Beaufort Laboratory.

Yet I had somehow never seen any historical accounts of the agar industry. Even after I found these photographs and began to look for articles or books that might have discussed it, I found only a couple of brief accounts that were written 75 years ago by one of the scientists involved in the agar facility.

Needless to say, my curiosity was aroused. As a historian, I have always been interested in the ways that our lives are entangled with the sea and I felt as if I had missed something important.

That curiosity led me on a bit of a deep dive into subjects that I could never have imagined studying: the history of agar, the ecology of seaweed, and the story of the wartime crisis that led to seaweed harvesting and the construction of the agar factory in Beaufort.

* * *

I began my research by learning more about agar and its history. With a little bit of digging, I soon learned that China, Japan, and other East Asian countries had been using seaweeds extensively as food, medicine, and fertilizer since at least the time of Confucious.

The invention of agar came out of that traditional knowledge of seaweeds and their uses.

By all accounts, agar was invented in Japan. The production of agar in Japan was first documented by Western observers around the time of the American Revolution, but it is believed that Japanese cooks had been using agar in soups, desserts, and other foods long before that time.

Agar was the first seaweed product that was traded extensively in international markets.

According to a scientific overview of the agar industry published soon after the Second World War, approximately 500 small factories in Japan were making agar by the turn of the 20th century. By then, Japanese firms were already exporting large quantities of agar to Europe and the Americas.

Scattered over the Japanese main island of Honshu, those factories were what we might call “craft industries” today: local and using traditional, hand-crafted techniques, not reliant on electricity or machinery.

Cooks in Japan first used agar in their kitchens, but agar spread from Japan to cuisines in many parts of East Asia and the Pacific. In fact, the name “agar” comes from a Malay word for red algae, agar-agar.

The first use of agar as a growth medium for bacteria was not in Japan or elsewhere in East Asia, however.

That use for agar first began in Germany in the late 19th century. In the 1880s, scientists in the great German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch’s laboratory first used agar as a growth medium for bacteria.

Using agar, they succeeded in isolating the bacteria that caused tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax for the first time. Discoveries that saved the lives of untold millions.

It was agar’s exceptional ability to serve as a bacterial medium that led to the agar factory in Beaufort.

Prior to 1939, the vast majority of the world’s supply of bacteriological agar came from Japan, where agar was produced mainly from a red seaweed whose scientific name is Gelidium corneum.

With that supply cut off by the war, many U.S. Allies began seeking to develop their own internal sources of agar.

In a time of war, the availability of bacteriological agar was especially important in medicine.

Physicians and microbiologists sometimes relied on agar to grow bacterial cultures in order to identify diseases. More commonly, they relied on agar to produce vaccines and to grow Staphylococcus aureus, one of the leading causes of wound infections, and other bacteria to test the potency of penicillin.

Great Britain was among the first countries that recognized a shortage of agar as a national emergency. Beginning in 1942, British leaders initiated the large-scale harvesting of red seaweeds on England’s west coast and to a lesser extent in Northumberland.

The United States also declared agar a “critical war material” and moved to assure an adequate supply of agar in 1942.

According to an April 1943 AP story, the federal government’s War Production Board, or WPB, froze the nation’s entire stock of agar in 1942, restricting its use to medical and pharmaceutical purposes. In addition, the WPB authorized the creation of a federal stockpile of 750,000 pounds of agar, more than twice what was available in the country at the time.

The AP story also noted that the U.S. had been using approximately 600,000 pounds of agar a year prior to the war, nearly all of it obtained from Japan.

On a quest to develop a domestic supply of agar, the Food and Drug Administration’s E. G. Poindexter seems to have started the inquiry that led to the agar factory on Pivers Island.

On a tour of the southern coast in 1942, Poindexter met with Dr. Harold J. Humm, a young marine scientist at the Duke University Marine Laboratory, which had opened on Pivers Island a few years earlier.

A specialist in marine alga and marine bacteriology, Humm was later the marine lab’s director and eventually founded what is now the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Sciences.

At Pivers Island, Poindexter and Humm discussed the possibilities for locating seaweeds suitable to the production of agar on the East Coast of the United States.

According to an Oct. 5, 1944, Beaufort News article, the War Production Board, based on Poindexter’s recommendation, soon funded Humm to survey sources of red seaweed that could be used to produce agar.

With that support, Dr. Humm explored coastlines from Chesapeake Bay to the Florida Keys and along the Gulf Coast.

He also began experimenting on making agar with seaweeds found in the vicinity of Pivers Island. By June 1942, he was focusing especially on a red seaweed that locals called “red moss” that was common on the area’s beaches at low tide and in local waters up to a depth of about 60 feet.

Dr. Humm described his research on seaweed and agar in an article called “Agar: A Pre-War Japanese Monopoly” that appeared in the journal Economic Botany in 1947.

A few years later, he published a more comprehensive survey of his work on agar and on the history and uses of agar in general in a chapter of a larger scientific work edited by Donald K. Tressler and J. M. Lemon titled Marine Products of Commerce: Their Acquisition, Handling, Biological Aspects, and the Science and Technology of their Preparation and Preservation (1951).

The experiments showed promise. According to Dr. Humm’s findings, two red seaweeds, Gracilaria confervoides and Gracilaria foliifera, both in a genus commonly called “Irish moss,” were available at commercially viable levels in the intertidal zones on that part of the North Carolina coast.

Persuaded by Dr. Humm’s research, a private firm called the Van Sant Co. began recruiting fishermen to harvest the seaweed and also began fashioning a small experimental facility. I am a bit unclear if that temporary facility was located in Beaufort or on Pivers Island.

The company had been established by Harvey G. Van Sant, the driving force behind a biochemical firm called the American Chlorophyll Company that was based in Washington, D.C.

Several years later, in 1947, Harvey G. Van Sant described the American Chlorophyll Company as “a pioneer in the field of processing and refining natural pigments and vitamins” from organic sources for use in “foods, cosmetics, feeds, and pharmaceuticals.” The Palm Beach Post, April 4, 1947.

During the spring and summer of 1943, the Van Sant Co’s scientists also undertook research on seaweed harvesting methods and on the preparation of agar.

That research was done in cooperation with Dr. Humm, as well as with scientists at the U.S. Government Fisheries Laboratory, also on Pivers Island, and other government fishery scientists.

“We Could See Ships Burning”

One of the scientists who supported the company’s agar research was Dr. Herbert Prytherch, the director of the U.S. Government Fisheries Lab. His son later wrote a brief reminiscence of his childhood that gives a sense of what the Second World War was like in Beaufort that is not revealed in our photographs.

In his excellent history of the U.S. Government Fisheries Lab, NOAA scientist Douglas A. Wolfe quoted Herbert Prytherch, Jr.:

“The port terminal at Morehead City [a half-mile west of Pivers Island] afforded safety for a number of ships, and they would stay there until dark of the moon came each month.

“German submarines would lurk offshore, waiting for these ships to leave the harbor. Late at night we would hear the distant thud of torpedoes and depth charges. Next we would hear endless sounds of airplane engines, followed by more explosions. Sometimes on the morning after, we could see ships burning….

“During these days the beaches were black, covered with oil. Many sailor caps were also found, and sometimes bodies.”

By November 1943, the Van Sant Co. had begun to produce commercial agar, though again I am unsure if those first efforts were undertaken somewhere in Beaufort or on Pivers Island.

Soon local fishermen with boats piled high with tons of seaweed were a not uncommon sight on that part of the North Carolina coast.

The fishermen would say that they were going out “mossing.”

“Thousands of unexpected dollars have found their way into fishermen’s pockets and `mossing’ has begun to take its place with clamming, crabbing, fishing, and other industries,” The Beaufort News announced.

Over the course of that fall, the fishermen delivered an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 tons of seaweed to the company’s dock.

For the old salts at least, collecting seaweed was nothing new, though they had never done it anywhere close to that extent. But old timers still used seaweed as a fertilizer in their gardens, and many fishing people used that same red seaweed to stuff the mattresses where they slept at night.

Sometime that fall of 1943, for reasons that are unclear to me, Harvey Van Sant sold the company to a M.W. Stansfield, a businessman who renamed the firm the Beaufort Chemical Co.

Stansfield also purchased a 40-acre waterfront lot a few miles away in Lennoxville, on the far side of Beaufort, and began to build the agar facility that we see in these photographs from the State Archives.

In a Feb. 21, 1943, article in the Raleigh News & Observer, reporter Amy Muse described how the company’s workers followed a method of making agar that was very similar to the traditional methods used in Japan.

“The [sea] grass is spread out to dry and bleach for several days, during which time it is sprinkled at intervals with sea water. Then the cooking: The grass is boiled in a generous supply of water, resulting in a soupy product. This is strained through cloth and poured into shallow pans, where it solidifies like a clear gelatin. It is from this, through a scientific process, that pure bacteriological agar is obtained.”

Muse left out a step or two, a great deal of filtering, dehydrating, freezing, chemical additives, drying, and milling, but that was it in a nutshell.

I have not found historical records on the quantity of seaweed harvested at the company’s plants, or on the quantity of agar produced at them, or of the company’s profits.

However, I do know that the local agar industry was relatively short-lived. With the support of the War Production Board, the Beaufort Chemical Co. seemed to thrive during the war and played an important part in helping the country to overcome its reliance on Japanese agar.

But by the winter of 1945-46, soon after the war’s ghastly ending at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the company’s leaders were already saying that the local supply of Gracilaria confervoides and Gracilaria foliifera, the “red mosses” necessary to make agar, was dwindling.

The company soon shuttered its facility in Lennoxville and relocated its base of operations to the Florida coast. In 1948, the Beaufort Chemical Co.’s directors declared bankruptcy.

At that time, another company, Sperti, Inc., bought the company’s plant in Lennoxville.

Named for its president, a Cincinnati research scientist named Dr. George Sperti, Sperti, Inc. continued to make bacteriological agar and apparently also agar for culinary and other uses for a few more years.

Today Dr. George Sperti is remembered most often for inventing another product connected to the sea– the hemorrhoid treatment Preparation H. The original formulation of Preparation H included shark liver oil as a central ingredient.

Dr. Sperti closed the facility sometime in 1951 or 1952. Then, in the summer of 1953, the company’s main processing plant on Lennoxville Road, abandoned at the time, burned to the ground. The agar industry’s brief moment on the North Carolina coast was over.

* * *

Special thanks to Douglas A. Wolfe for sharing his extensive knowledge of Pivers Island’s history and the work of its marine laboratories with me.

This is the 2nd in my “Working Lives” series that looks at the stories behind a collection of historical photographs that were taken on the North Carolina coast between 1937 and 1953.

The photographs were originally taken for a state agency called the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development. Today they are preserved at the State Archives in Raleigh.