A recent U.S. Geological Survey study projects that rising sea levels and stronger, more intense storms will exacerbate four specific coastal hazards and associated management challenges for Cape Lookout National Seashore.

Rising waters and eroding or sinking lands may be unsurprising on the coast, but the findings are troubling for anyone on or near a barrier island, those slivers of sand so popular with visitors and vital to protecting mainland folks.

Supporter Spotlight

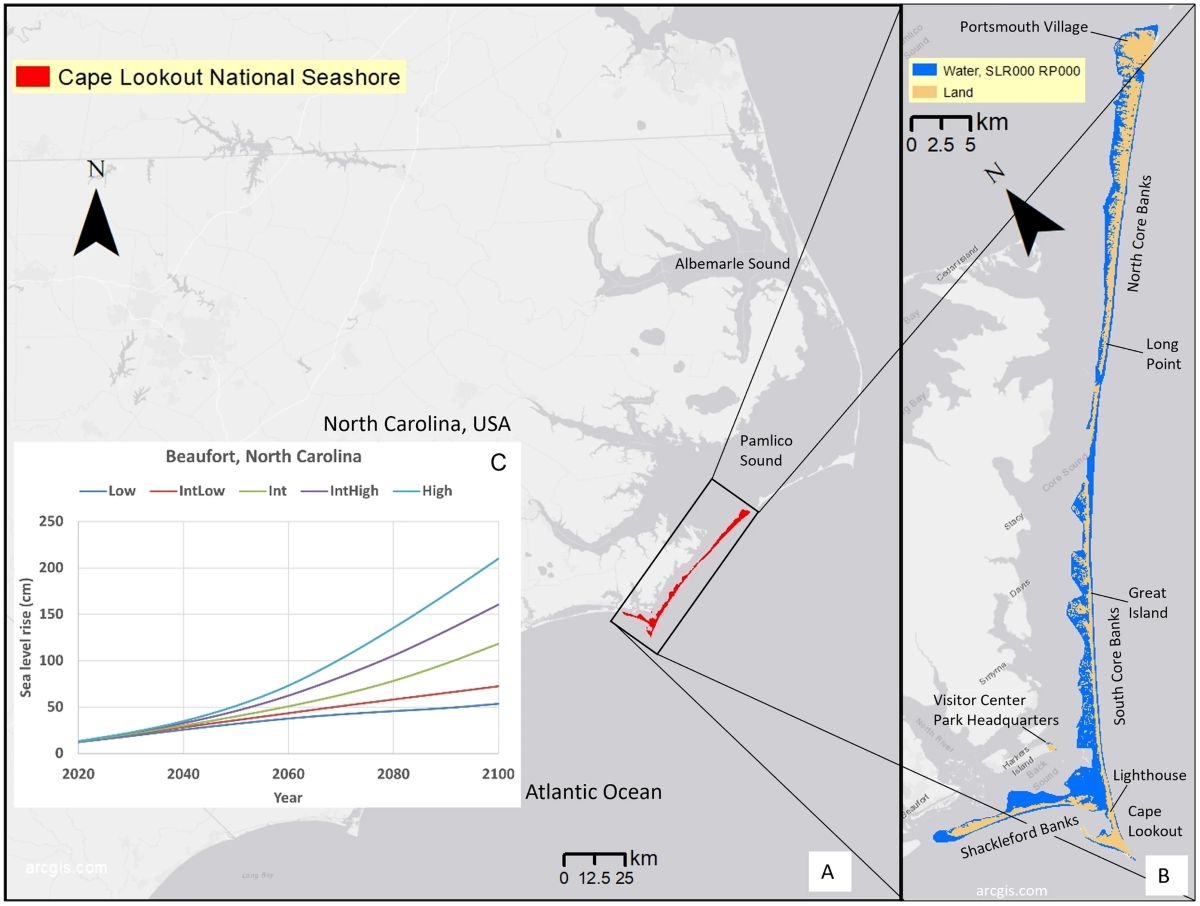

“Accelerating sea level rise (SLR) and changing storm patterns will increasingly expose barrier islands to coastal hazards, including flooding, erosion, and rising groundwater tables,” according to the study titled, “The projected exposure and response of a natural barrier island system to climate-driven coastal hazards,” published in Nature scientific reports.

The authors explain in the study that their findings illustrate “viability of this barrier island system will be compromised by increasingly severe flooding, rising groundwater, erosion, and land subsidence over the next century.”

Three of the paper’s authors, oceanographer Jennifer Thomas, coastal geologist Patrick Barnard and research oceanographer Sean Vitousek, told Coastal Review in a joint response that the study looks at the coastal hazards related to sea level rise and storms on Cape Lookout National Seashore, which is just a short boat ride from mainland Carteret County.

The scientists are based at the Geological Survey’s Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center in Santa Cruz, California.

“This study shows model projections of overland flooding, groundwater depths, and shoreline change for a series of plausible sea level rise and storm scenarios over the next century. Vertical land motion is derived from satellite observations,” the scientists said.

Supporter Spotlight

The team explained how sea level rise can increase the impacts of coastal hazards.

A higher sea level means that high tides can more easily cause sunny day, or nuisance, flooding, and that waves and storm surge can reach higher elevations, which can then lead to overwash, erosion and flooding farther inland. This can also cause groundwater tables to rise, they said.

Since the land is also sinking, that makes relative sea level rise even higher, intensifying these hazards.

Barrier islands, like those in the Cape Lookout study area, “buffer storm impacts for the mainland coast. However, the barrier islands themselves are at an increased risk compared to mainland coasts, as they can experience the hazards of SLR and storms on all sides. Vulnerable barrier islands can lead to more vulnerable mainland coastlines in the future,” the study states.

The researchers told Coastal Review that without intervention, flooding and erosion will be pervasive across barrier islands over the next century.

“As these islands are the first line of defense for mainland communities, reduction in this natural protection will create more hazard exposure in the future,” the team continued. “Managing coastal resources under a changing climate will be extremely challenging.”

Cape Lookout Superintendent Jeff West told Coastal Review that the report findings confirmed what the park staff has seen happening over the years: “an increased number of flooding events, and more devastation” from storms.

“Not only does it confirm what we have been seeing, but it helps detail what to expect in high visitor use areas — places we have infrastructure assets,” West said.

Managed by the National Park Service, Cape Lookout is made up of barrier islands off mainland Carteret County, and is home to several threatened and endangered species, a herd of wild horses, the still-operational 1850s Cape Lookout Lighthouse, historic villages, campsites and ferry landings.

Based on these projections, West said that he thinks the park service and visitors should expect to see places they love begin to disappear over the next two decades.

“They will have environmental impacts that change where and when they can visit, and I expect they will see a change in services they have come to expect and that the NPS provided.”

Cape Lookout Wildlife Biologist Sue Stuska monitors the horse herd along with management partners the Foundation for Shackleford Horses Inc. She told Coastal Review they are trying to determine how to plan for the herd with the upcoming changes.

Models project that emerging groundwater will likely not cause flooding on Cape Lookout National Seashore because, by the time sea level rises high enough to cause that, overland marine flooding will already be occurring, according to the study.

Stuska said that while she has not seen groundwater emerging at the surface, “I have documented three new places in the middle (between ocean and sound) of Shackleford Banks where the horses are digging for fresh water in swales where they never dug before. I have theorized that the water table is rising, giving them access there where it would have been too deep before.”

Rising sea level, higher risk

The Geological Survey team explained that the National Park Service requested summaries of recent research of the region relevant to coastal management concerns at Cape Lookout National Seashore.

The team pulled data specific to the national seashore and determined that with 0.5 meters, or 1.6 feet, of sea level rise, 47% of barrier island surface area would flood daily, and the type of storm nearly certain to strike each year would flood 74% of island surface area. During a storm of the intensity likely to come only once every 20 or so years, more than 85% of the island can be expected to flood.

Flood risk for extreme storm events doubles with just 2 to 4 inches of sea level rise, “and therefore, in the coming decades, hurricanes will likely cause more severe impacts than in the recent past for coastal North Carolina,” according to the study.

And a third of Cape Lookout National Seashore is currently sinking at a rate of more than 2 millimeters — about the thickness of a nickel – each year, further accelerating erosion and habitat loss.

With 3.3 feet of sea level rise, models project that shorelines will retreat an average of 178 meters, or 584 feet, if there’s no intervention. That would cover more than 60% of the current island width at its narrower locations. Shoreline retreat is what happens when an area experiences long-term erosion.

Researchers note in the study that the results are relative to sea level rise values, not the amount of time those levels are anticipated to be reached, to “decouple the uncertainty of timing” from future sea level rise. “However, in the Discussion section, we relate results to time, using the SLR values closest to local estimates for the intermediate-high scenario for the years 2050 (0.46 m) and 2100 (1.60 m),” or 1.5 feet in 2050 and 5.24 feet in 2100. Authors cite projections that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released in 2022.

The researchers said it’s up to the National Park Service to make the difficult decisions on how to manage sea level rise and storm impacts. “Hopefully this study can provide valuable information as a guide to the short- and long-term coastal hazards to consider.”

Cape Lookout plans on sea level rise

Superintendent West said that while management is facing “mounting pressure to balance the needs of human safety and environmental preservation in a landscape increasingly shaped by climate change,” as the Dec. 4, 2024, press release states, he recognizes how much these changes will affect those fond of the national seashore.

Federal and state managers are facing pressure, “but people who live and work in coastal areas, people that visit and love these areas, well, they will suffer from emotional loss,” West said.

He added that while the park service has planning in place and is adaptively managing its resources, people tend to reject change.

“Gradual devastating change is harder to accept. You don’t see it unless you are living it, and even then, people can get use to things and then fail to see the bigger picture,” he said.

Cape Lookout changes every day. Five years from now it will be different than it is today, 10 years from now it will be dramatically different, West said.

The park service is taking action, West said, but, “I am not sure how humans truly plan for that which they do not know or fully understand. Still, we are trying.”

Park officials had already assessed Cape Lookout’s built assets, like the lighthouse and historic structures, and they know how vulnerable they are to storms, sea level rise, storm surge, wind and historic events.

“We know which buildings we are not going to rebuild in their current locations should they be damaged, we know the options we have for each asset,” which are to raise and rebuild with sustainable materials, move, or demolish and abandon the location, West said. “A number of structures that were continually battered by storm have been demolished and removed. We are not investing repair or rehabilitation dollars in structures that have that kind of exposure. There are currently five additional structures on that list that will not be reconstructed if they are storm damaged or flooded.”

New construction takes all factors into consideration, West said.

He said the camp on North Core Banks is an example. Long Point Camp was at one of the narrowest and most frequently affected parts of the island, with 7,000 feet of underground utilities, generators, and wooden buildings. It was subject to both ocean and sound-side flooding.

West said the park service replaced underground infrastructure routinely, and has done over 20 reconstruction or repair projects after storms between 1995 and 2019, when Hurricane Dorian devastated the camp yet again.

They found a site 5 miles to move the camp that’s north on one of the highest parts of the island. The new site sees little coastal erosion.

“The camp itself is designed to take environmental impacts yet be low-cost to build and maintain. Almost no underground utilities, all structures on raised platforms, buildings are principally oceangoing containers modified for residential or utility use, all power is provided by solar and wind generator systems,” West said.

Construction started in December.

To repair or rebuild docks, the park service elevates the structure and uses decking made of concrete that allows water to flow through without undermining the supporting structure, and pilings are driven to a minimum depth of 28 feet.

“We did a large beach nourishment project at the Cape Lookout Lighthouse to protect the lighthouse complex and are currently monitoring it for erosion. Once the data is in, we will look at options to try and hold that beach in place,” West said of the work completed early last year.

“Marsh restoration and protection are currently being planned,” West said. The state will lose about 85% of its current marsh area over the next 25 years.

“We are starting the process of protecting what we have and restoring some of what we lost now to try and stay ahead of sea level rise,” he explained.

West said that the park service approaches each project by posing a series of questions with sea level rise and storms in mind: “Do we need it? If we need it, is it in the right place and/or where is the right place? Can we build it better? Can we fund it? If we can do it, should we?”