Deep-diving whales that rely on sound rather than vision to hunt in the ocean’s darkest depths are confusing plastic marine debris for prey, new findings suggest.

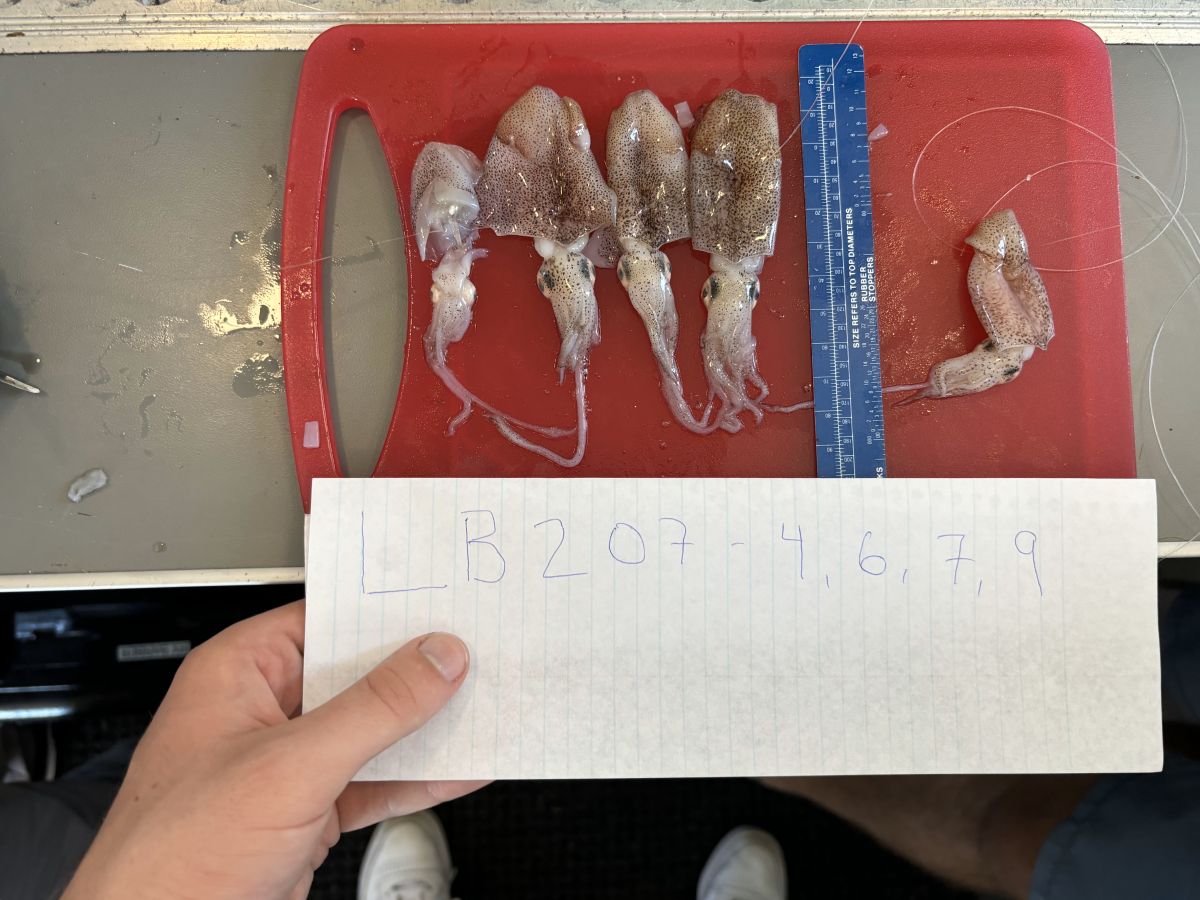

For the study, “Acoustic signature of plastic marine debris mimics the prey items of deep-diving cetaceans,” researchers from Duke University as well as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, compared the way sound bounces off plastic that is floating underwater to that of typical whale prey, in this case, squid and squid beaks.

Supporter Spotlight

It is widely assumed that seals and toothed whales mistake plastic for food because of appearance, particularly plastic bags and films that look like squid and jellyfish, according to the study, but that doesn’t explain why deep-diving species like sperm whales and beaked whales that use echolocation are ingesting plastic. To echolocate, the whale emits sounds that reflect off an object. The whale then interprets the object’s target strength, or measurement of the intensity of the sound’s echo.

“Assuming these animals are ingesting plastic at depth and not at/near the surface, they are consuming plastic without visually identifying it. Deep-diving toothed whales may therefore be misinterpreting acoustic cues when echolocating; presumably plastic’s acoustic signature resembles that of primary prey items, driving plastic consumption,” the study states.

Researchers for the new study found that 100% of the plastics they tested that are typically found in stomachs of stranded whales — plastic bags, rope and bottles — have either similar or stronger acoustic target strengths, which is how strong a sound wave is reflected off an object, compared to that of squid.

The findings support the study’s hypothesis that deep-diving whales are consuming plastic because of “a misperception of acoustic signals.”

Duke University doctoral candidate Greg Merrill Jr. led the peer-reviewed study published a few weeks ago in Science Direct.

Supporter Spotlight

From California, Merrill has been at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort for the past few years to examine the impacts of microplastics and large plastic marine debris on whales.

Merrill graduated from the University of California, Davis, with a bachelor’s in biological science in 2014. He then pursued his master’s at the University of Alaska Anchorage, where he worked with northern fur seals, trying to understand how climate change was impacting their breeding success. That experience planted the seed for this study.

While he was working on his master’s, Merrill said he spent many months on the remote Pribilof Islands of Alaska in the middle of the Bering Sea where the threatened northern fur seal breeds.

“All too common a sight was a seal entangled in plastic debris, such as packing bands and discarded fishing net. The animals often died as a result. This motivated me to study the impacts of plastic pollution on other marine mammals like the deep-diving sperm whales and beaked whales off the North Carolina coast,” he said.

Merrill explained that these animals, in particular, hunt especially deep in the ocean where there is no light to see. Instead, they rely on echolocation, or biosonar.

“In other words, they use sound waves to locate and identify food. Because we know from autopsies of stranded whales that they are eating plastic, it occurred to me that plastic may be causing whales to misinterpret their echolocation signals. So, we wanted to see if that was true,” Merrill explained.

He said in simple terms, the study was to see if plastic in the water confused echolocating whales into believing it was instead food.

“We collected plastic trash from the beach and then blasted those objects and whale prey with various sound waves at sea using an instrumented called an echosounder mounted to the bottom of our research vessel. The plastic objects were strung up on monofilament fishing line and held underneath the instrument while the measurements were recorded,” he said.

An echosounder is a device that uses sound waves to measure the water depth or where objects are in the water. The hull-mounted echosounder tested three different sounds at the same frequencies of whale clicks.

“Based on the measurements we recorded, plastic has similar or stronger echoes than the whale prey items we tested. The way an object reflects sound depends on what it’s made of,” Merrill explained, for example what the plastic is made of or (its) thickness. “Plastic unfortunately ‘sounds’ the same as whale food.”

The study notes that plastic pollution in the oceans is pervasive and increasing with more than 1,200 marine species known to ingest plastic debris. For marine mammals, there are hundreds of examples of whales, seals, sea lions and manatees “consuming plastic, ingestion of which constitutes a major threat to individual health,” the study states. “Consequences of macroplastic ingestion include abrasion and perforation of tissues, infection, reduced reproduction and growth, suffocation, clogging the baleen filter false satiation, occlusion of the gastrointestinal tract, starvation, and ultimately death.”

The finding underscores just how complex the plastic pollution issue is, Merrill said, adding the most common plastics found in whale stomachs are plastic bags, single-use packaging, and fishing gear such as nets, ropes, and lines.

“I’m not sure many people would have ever imagined that the way something sounds could have such big consequences as affecting large whales who hunt so very far away from human activities. The scale of the plastic pollution problem is enormous, a global issue that requires policy action at the level of local all the way to international governments. And it is having so many impacts on our planet and on human health, Merrill said.

He encourages “anyone who cares about this issue” to contact their elected officials and let them know you want to see action on this front.

Michael Cove, a conservation ecologist and mammologist, told Coastal Review that “this research was fascinating and provides some much-needed insights into how and why marine mammals might intentionally ingest plastic waste that could severely impact them and ultimately lead to their deaths.”

The research curator for the mammalogy at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, Cove explained that so much of our perception of food and foraging is based on visual cues, because humans use their eyes to find food, “and that has been shown in research with seabirds and sea turtles, but many deep-sea-diving marine mammals are going off of sound through echolocation and not sight.”

Studies like Merrill’s show that there’s still a lot to learn about how some of the sperm and beaked whales forage. In many cases, there’s still much to understand about what they forage because they are feeding at such great depths, Cove explained. He has often assumed that most plastic consumption is incidental or intentional based on visual cues, citing Mylar balloons looking like squid as an example.

But this study, “points to intentional consumption of plastics based on their sound, which spells trouble for deep sea diving whales since the accumulation of plastic in our oceans continues to increase and it persists for thousands of years.”

Cove said that this work highlights and renews that calls to end balloon releases, especially in coastal areas, should be revisited and policies to reduce plastics entering marine food webs will be critical to maintaining maintain diverse marine mammal communities into the future.

“After all, marine mammals along with sharks and large fishes make up the top of the food chain, which largely regulate the lower trophic levels (links in the chain) and the loss of any species and that top-down regulation can have cascading effects throughout the community that could even influence fisheries and ecosystem health processes well beyond the deep ocean,” he said.

Coastal Review will not publish Monday in observance of Veterans Day.