If North Carolina beaches are going to keep up their tug-of-war with the sea to maintain robust ocean shores, they’re going to need sand and a lot of it.

But, in an era when mining sand and pumping it onto beaches has become a go-to means of fortifying shores against erosion and storms, finding that just-right type of sand and enough of it for the foreseeable future might prove to be quite the challenge for many of the state’s coastal communities.

Supporter Spotlight

The dilemma is that beneath the surface of the vast Atlantic Ocean stretching from our shores, the amount of prized “beach-quality” sand needed to replenish them is finite.

There are, “critical sand shortages” across regions off North Carolina’s coast, according to a 2020 study by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in partnership with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM.

Federal agencies are being asked to look elsewhere and explore potential untapped sand sources beyond the boundaries of state waters, miles and miles out to the outer continental shelf.

In return, those agencies are relaying a message to coastal communities throughout the country – it’s time to stop thinking about individual project needs and focus on a more regional approach if you want to keep putting sand on your beaches.

“We’re seeing this challenge through the South Atlantic region, call it ‘sand wars’ or ‘competing uses of the same resource,’” said Doug Piatkowski, a physical scientist with BOEM’s Office of Strategic Resources. “There’s a real need to start thinking about what we do know about offshore resource availability and then how we maximize use in a more holistic way, systems’ say, so that we can optimize what little resource we have.”

Supporter Spotlight

A century of coastal engineering

Little more than a century has passed since the first U.S. beach got sand from offshore to replump its eroded shoreline.

Since 1923, when Coney Island, New York, officially became the birthplace of the engineered beach, more than 1.5 billion cubic yards of sand has been dredged and injected onto the shores of some 475 communities in the country.

More than 3,200 sand projects have been completed on beaches from California to Florida to New York over the course of the last 100 years. Many of the communities that account for that number have renourished their beaches multiple times, according to the South Atlantic Coastal Study.

North Carolina is one of six coastal states that has placed a large portion of that total sand volume — more than 80% — on its shores, according to a beach nourishment study published in January 2021.

Carolina Beach has the distinction of being the first to have a federal beach erosion-control project completed in 1964.

Since then, the Army Corps has authorized dozens of federal projects, which entail routine sand nourishment throughout a period of 50 years.

Between 2010 and 2020, a total of 37 million cubic yards of sand was placed on U.S. beaches each year, according to the South Atlantic Coastal Study.

In the South Atlantic region, more than 1.3 billion cubic yards of sand is required to support the region’s 50-year sand needs. More than 1.56 million cubic yards of sand resources have been identified to fill those needs.

An evolving theme ‘many aren’t talking about’

That sand surplus isn’t expected to last.

“While regional sand resources are greater than documented sand needs as of today, economically viable long-term sources are limited in many areas across the region,” according to the study.

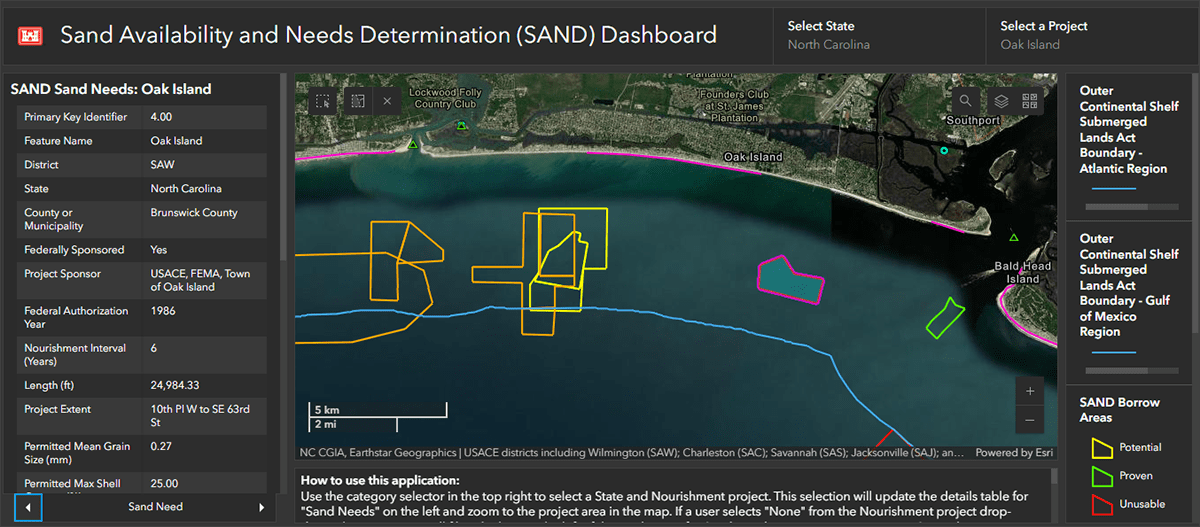

The South Atlantic study, also referred to as Sand Availability and Needs Determination, or SAND, was the first in which the Corps was given funding to do a regional assessment of sand needs.

It found that sand shortages were documented in every state within the Corps’ South Atlantic Division and identified “critical sand shortages” in regions of North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama and Mississippi.

“If we were to continue at the rate that we’re going … we have a lot of work to do to figure out kind of this supply-and-demand assessment, realizing with climate change and increased storm frequency and this continued demand for sand that we’ve got to do a better job at assessing where this resource availability is, what conflicts may exist in their use and then, over this next 50-year horizon, really have a more realistic understanding of availability and what we can do in terms of meeting the resilience plans to address the need,” Piatkowski said.

Now, more than ever, it is important to recognize these regions are all within one system, he said.

It’s an “evolving theme that many aren’t talking about,” Piatkowski said.

But that isn’t to say that all beach communities are behind the regional-thinking curve.

Carteret County, for example, is considered a leader in its long-term management of available sand options to meet the needs for all of Bogue Banks. The 25-mile-long barrier island is home to Atlantic Beach, Indian Beach, Pine Knoll Shores, Salter Path and Emerald Isle.

And Dare County is starting to think longer-term and look more broadly at its potential sediment availability options, Piatkowski said.

“This is something that BOEM’s trying to kind of message to the coastal stakeholder communities that, ‘Look, it’s beginning to be a scenario where you’ve got multiple interests and multiple needs all within one system and we need to be smarter about figuring out the dynamics of what is the underlying geology for the sediment that we do have. Why is it there? What are the transport processes in the location that we’re dredging it from?’ And then, where we’re placing it because, at the end of the day, if two beaches are connected, that sediment is ultimately moving in that system,” Piatkowski said.

Sand-challenged Long Bay

To understand the complexities faced by beach communities that face critical shortages in sand nourishment sources look no further than Brunswick County.

According to the South Atlantic study, Brunswick County has a sand deficit of nearly 30 million cubic yards.

That’s because Long Bay is essentially a sand-starved area, one where there are vulnerable coastlines in need of hardy sand borrow sources.

“Due to the nature and location of the beaches, it’s more likely to find rock or clay material rather than beach-quality sand,” said Jed Cayton, public affairs specialist with the Corps’ Wilmington District, in an email response to Coastal Review.

Frying Pan Shoals, an area off the seaward southeastern side of Bald Head Island with millions and millions of yards of sediment sand, is federally recognized as essential fish habitat. That designation has kept it from being tapped as a sand borrow source.

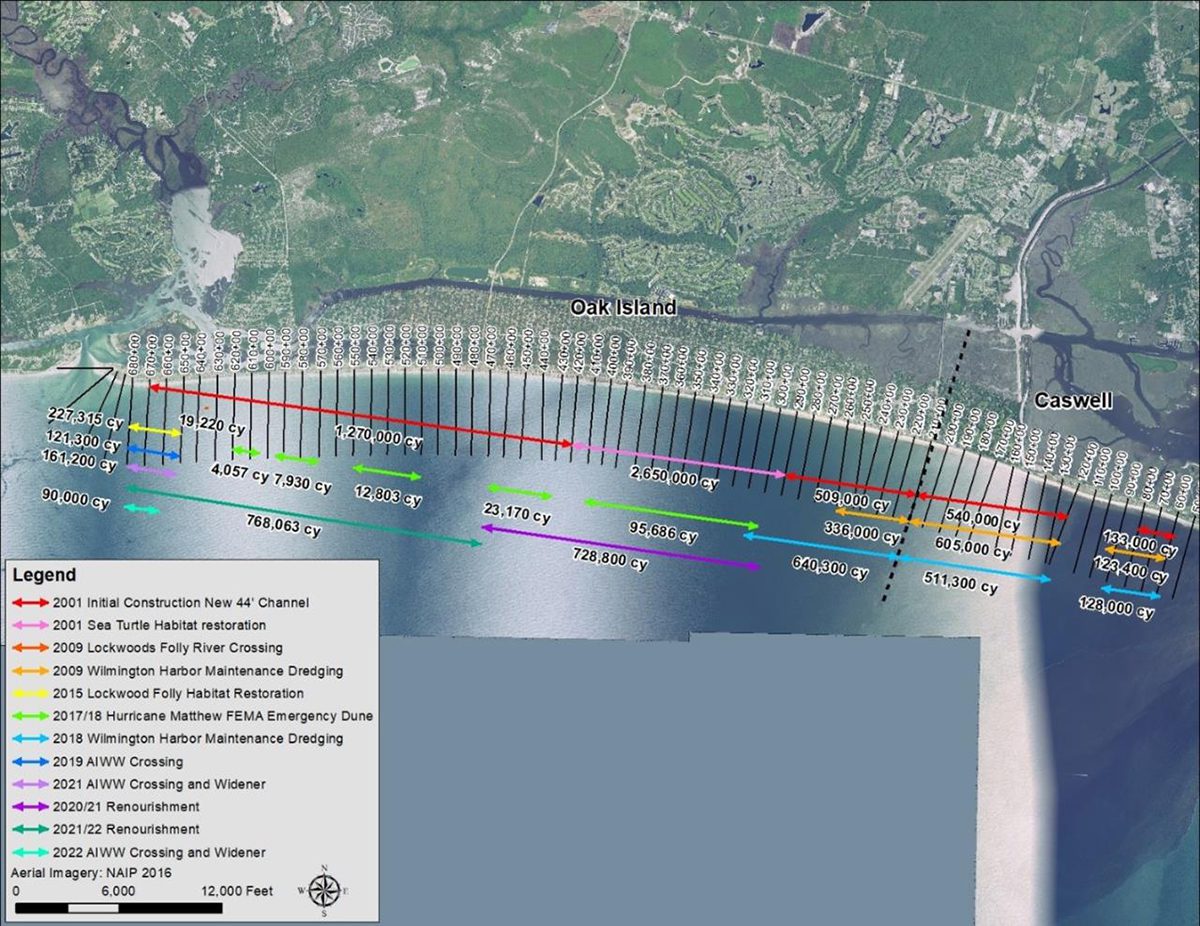

That has made Jay Bird Shoals, which is near the mouth of the Cape Fear River, a dredging hotspot for Brunswick beaches and, in recent years, the subject of growing contention between towns vying for sand security.

The town of Oak Island earlier this year received pushback from neighboring beach towns for including the inner ocean bar at the mouth of the river as a secondary sand source in its application for a beach nourishment project. The Brunswick beach town hopes to kick off the project this winter.

Oak Island is requesting to place up to 3 million cubic yards of sand along its 9-mile-long beach from a primary source some 18 miles offshore.

Oak Island’s project is estimated to cost $40 million. The town is awaiting a decision on the permit application.

The secondary source identified in Oak Island’s initial application is between Caswell Beach and Bald Head Island, which each argue that sand is crucial to their nourishment efforts.

In a board of commissioners meeting earlier this year, Caswell Beach Town Manager Joseph Pierce told board members, “If they pull that much sand from that area, our concern is that erosion is going to affect our east end, as well as Bald Head Island. There is a huge hole down there now where sand will continue to fall in, and it will affect both beaches,” The State Port Pilot reported.

Oak Island amended its Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit last month and removed its request to use the inner ocean bar as a secondary source.

The Corps and BOEM are currently studying a longer-term coastal storm risk management project for Oak Island. That study is projected to be completed in the fall of 2027.