The Inner Banks region of North Carolina is home to numerous of the state’s most historic small towns.

Settled early in the 18th century, these communities host famous restaurants, architecturally significant homes, and a wide variety of civic institutions. Some of these places have a reputation that reflects their importance and beauty, with towns such as Edenton and Washington being regionally or even nationally known. On the other hand, there are a number of unsung towns that have not been featured in the New York Times. One of these is Murfreesboro.

Supporter Spotlight

This gem on the Meherrin River has attracted civic and educational leaders for the past three centuries and is just as poised for growth today as it was in the colonial period.

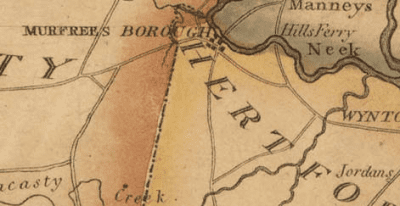

Murfreesboro was one of the first areas of North Carolina settled by the British. Its establishment was part of a wave of migration that extended out from the Albemarle Sound region in the early 18th century.

Following the earliest settlements and displacement of Native Americans like the Chowanoac, British settlers continued to seek more land for tobacco. As in Virginia and South Carolina, they moved west, marching across the colony until they reached the falls line in the mid-18th century. In North Carolina, the region closest to the Virginia border was also one of the most prosperous, as its inhabitants could trade with the wealthier Virginians and use their navigable rivers.

One of the rivers that crossed state boundaries was the Meherrin River. Passing through the home of the Meherrin Native Americans, this river provided an outlet to the Chowan River and the Albemarle Sound. Its miles of surrounding fertile farmland gained numerous tobacco plantations throughout the 18th century. By 1707, a small community had formed at a bend on the river.

Murfreesboro was incorporated as a town in 1787 and named for William Murfree, a local landowner and Revolutionary-era politician. The town’s heyday occurred during its first few decades. Architectural historian Catherine Bishir notes that in the early 1800s, the town “enjoyed trade that crowded the streets with wagons bearing produce from as far as the Blue Ridge and brought so many ships to its wharves that ‘one could cross the river on the decks of vessels lying in the stream.’”

Supporter Spotlight

The tobacco economy of the Murfreesboro area relied entirely on slavery. The town was a center for plantation agriculture, and enslaved workers constructed its buildings. The proximity of the Virginia border also made Murfreesboro a destination for free African Americans, many of whom were formerly enslaved and had escaped harsher conditions in Virginia. Hertford County, where Murfreesboro is located, had one of the largest populations of free African Americans in the entire state in 1860, according to historian John Hope Franklin.

Murfreesboro still retains a number of buildings from its earliest period as a town. These include nearly a dozen homes built before 1820, as well as at least three homes — Melrose, the Myrick House and the John Wheeler House — built in or around 1805. There is also the William Rea Store, which was built in 1790 and is one of the oldest commercial buildings in the state.

The antebellum period was also the beginning of Murfreesboro’s best-known site. North Carolinians’ zeal for education during the Revolutionary period led to the formation of a number of academies, along with the state university in Chapel Hill.

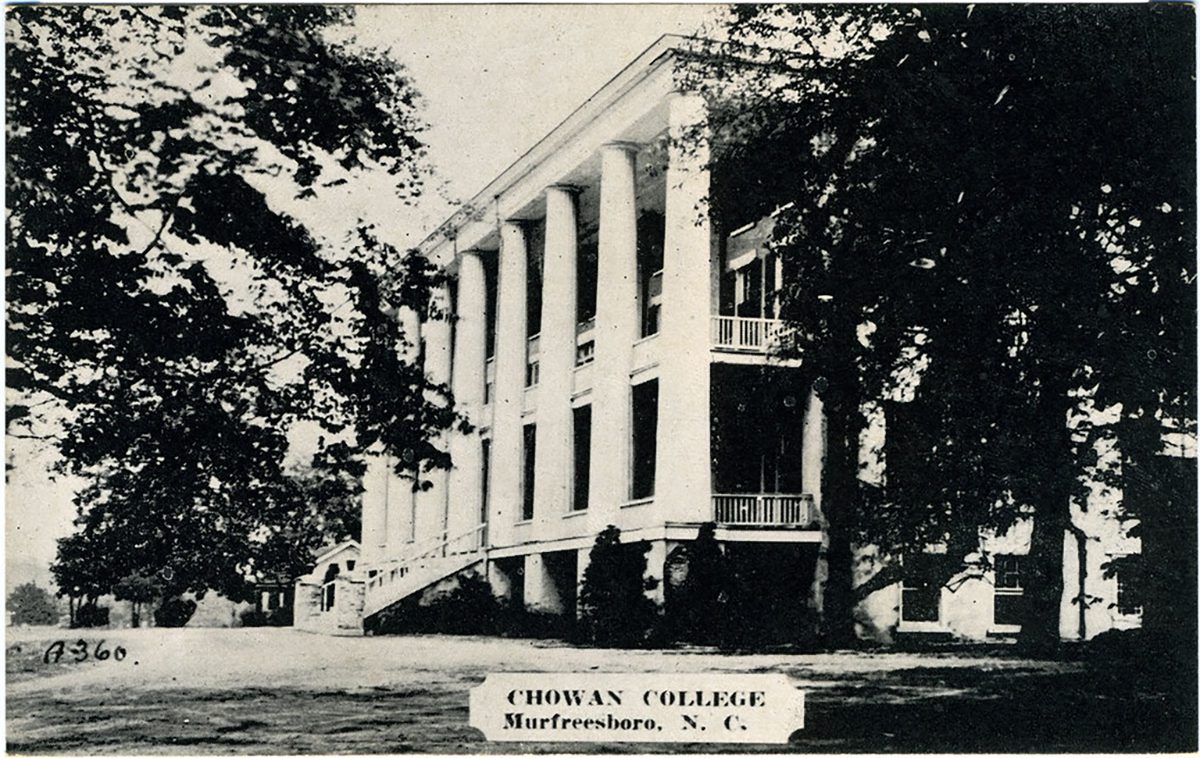

One of these institutions, Hertford Academy, was established in 1811 in a Murfreesboro home. It was eventually bought by local Baptists and became Chowan Baptist Female Institute, later, in 1910, Chowan College, and in 2006, Chowan University. The institution moved to its present flagship building in 1851. This structure, known as the Columns, is considered an excellent example of Greek Revival architecture and is one of the largest antebellum college buildings in the state.

The Civil War inflicted some damage to Murfreesboro. The town was attacked and looted by Union troops, but it was not burned like Winton, its neighbor to the east. As throughout the South, the war devastated the town’s economy. Tobacco declined in importance for decades. Most importantly, the abolition of slavery erased the forced-labor system upon which the entire region had relied entirely.

Like other towns of the time, Murfreesboro took a middle path as it recovered from the war. It did not embrace — or was not embraced by — industry to the extent that nearby towns such as Ahoskie or Elizabeth City had. Ahoskie, which was formed a century after Murfreesboro, passed the older town in population by the 1910 census. Still, Murfreesboro was eventually able to relax its reliance on cash crops, especially the traditional crop of tobacco. Murfreesboro had become a center for peanut cultivation as well as the home of an iron foundry and manufacturing plant by 1916.

The 20th century in Murfreesboro was defined by the growing importance of both industry and Chowan University. Murfreesboro became the home of Riverside Manufacturing Co., believed to be the world’s largest basket company, in 1927. The plant employed thousands of Murfreesboro residents for the next seven decades.

Outside of baskets, the university is a considerable draw. Chowan College closed for six years in the 1940s, but has prospered since reopening, and it became a four-year institution again in 1992. Chowan graduated a number of its best-known alumni in the late 20th century, including NBA coach Nate McMillan. Chowan counted 1,500 students in 2017, a notable achievement for a town with only about 2,800 full-time residents.

In recent decades, Murfreesboro has remembered its three centuries of history and embraced historic preservation and tourism. The Murfreesboro Historical Association incorporated in 1963 and now owns more than a dozen properties and hosts numerous events and tours each year, most notably a candlelight tour in December.

Murfreesboro is also home to the Brady C. Jefcoat Museum, a nationally known museum dedicated to the sprawling collection of everyday objects, antiques and historic artifacts owned by one man — who happened to have helped build the Memorial Belltower at North Carolina State University and dozens of other Raleigh structures — and displayed in the former high school.

While many small towns in North Carolina have at most one or two historic homes open to the public, Murfreesboro Historical Association James Moore credits the town’s commitment to sharing its history and preserving and promoting the college and the town since 2000. It has become a bedroom community to much larger, more bustling areas nearby. As Moore noted, “You can be in downtown Norfolk in an hour.” And as people continue to move to Murfreesboro, the community bolsters the historical association and provides it with the donations and interest needed to continue its work.

Today, Murfreesboro has carved its niche as a center of both education and tourism in the Inner Banks. It remains the second-largest town in Hertford County and continues to welcome new businesses such as restaurants, tattoo parlors, and recently a “barcade,” Insert Coin Arcade and Bar.

More people visit the town’s museums every year, and the Historical Association says it has the potential to expand its offerings and tours even further. Murfreesboro may not be the size of New Bern or have the prominence of Edenton, but it shows that the past — and historic preservation — can still be the future for North Carolina’s smaller coastal towns.