Getting to what remains of Buffalo City on the Dare County mainland isn’t easy.

Walking to the site where there’s not much left but is surprisingly intact, requires hip boots at least, though waders are a better choice, and being in reasonable physical condition since it’s a little bit more than a mile hike — or slosh — through what is truly trackless swamp.

Supporter Spotlight

It’s a good idea to go with someone who knows where they’re going, too, and, for good measure, go on a cool or cold day. Water moccasins are prolific in the swamp and there’s a reason the area is called Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

Related: As timber declined, Buffalo City loggers made ’shine

Buffalo City gained notoriety for its moonshine production during Prohibition, but there’s more to the now-abandoned town’s story than just logging and liquor. The remnants of two buildings where the mill town once stood are extant evidence of a wildly expensive insurance company fraud case during the 1910s.

Bill Barber of Columbia, in Tyrrell County, is the guide, leading this reporter to what remains of Buffalo City. He’s a retired forester with 40 years of experience, most of his career with Weyerhaeuser.

“I had several hundred thousand acres of land that was under my management,” he said, referring to his time with Weyerhaeuser. “I thoroughly enjoyed my career with them.”

Supporter Spotlight

No longer working in forestry, he has since had a chance to follow up on stories he had been told for years. Barber told Coastal Review that his mother had family who lived in East Lake and Buffalo City.

“There’s a lot of legends and a lot of lore about what went on at Buffalo City,” he said. “When I retired, I thought I just need to check into this, to really figure out what the story is. So, I started doing research on it.”

With about seven years’ worth of research behind him, Barber has published three books on the history of the lumber industry in northeastern North Carolina.

“Timber, Land & Railroads: A History of the John L. Roper Lumber Company” is an account of the timber boom following the Civil War; “Tyrrell Timber: A History of the Branning Manufacturing Company and Richmond Cedar Works” chronicles timbering operation in Tyrrell County; and “Buffalo City and the Blount Patent: A History of Logging the Dare Mainland” is history of land use by entrepreneurs and speculators on mainland Dare County.

With Barber leading, we come out of the swamp onto what passes for high ground.

There are the remnants of a substantial concrete building. A series of blocks rest on top of a solid concrete base with metal bolts still anchored to the concrete.

About 50 yards past that is what remains of a brick building. Vines grow up its sides and trees have taken root in what was once the floor.

The brick building was at one time a pulp mill and the concrete building was once a coal-fired generator that powered the mill. The only visible remnants of Buffalo City, they appear incongruous in the setting.

What was once a thriving, if small, lumbering town has vanished.

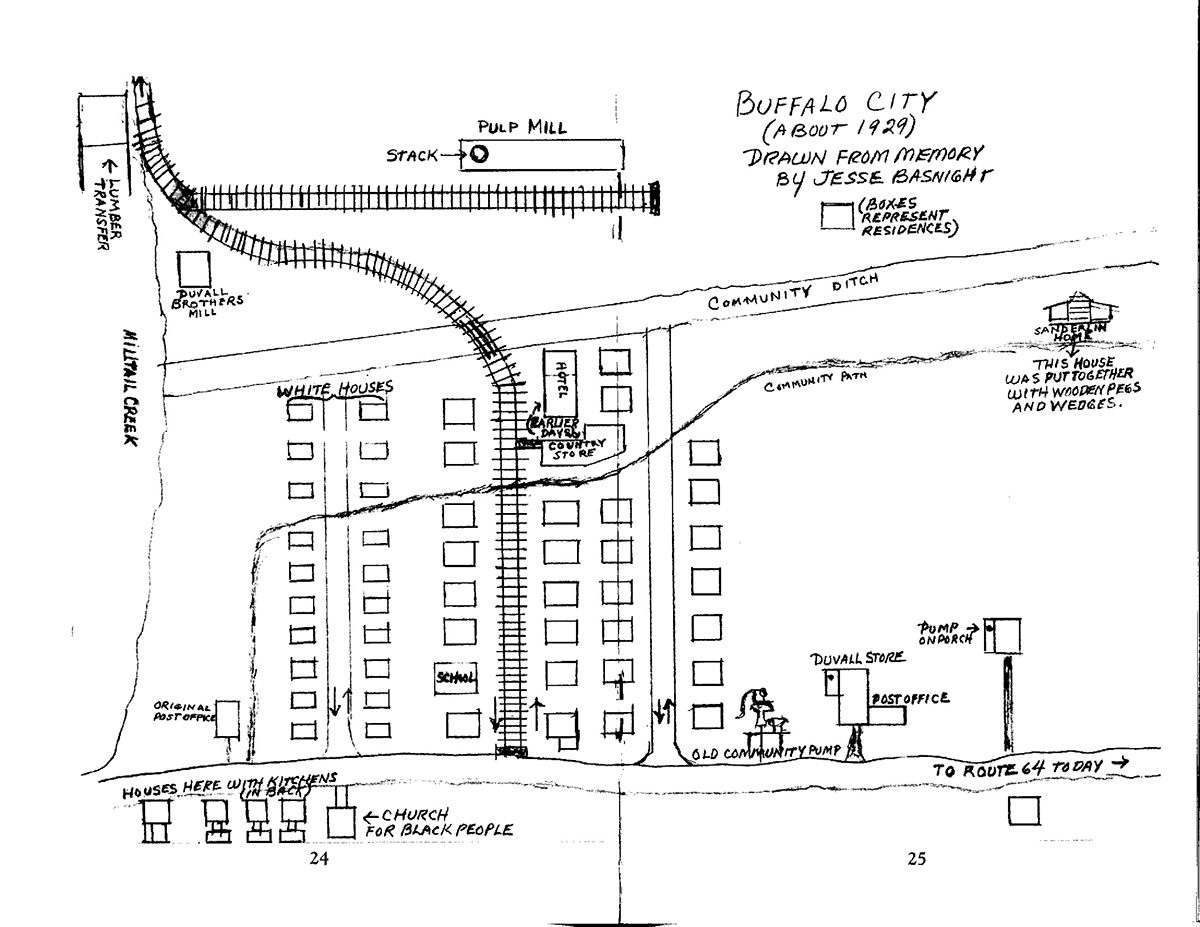

A map drawn from memory by one-time resident Jesse Basnight depicts about 35 homes, a post office, country store and hotel. The 1910 census records 548 residents in East Lake Township. It is possible some workers were missed if they were in a lumbering camp, but it’s doubtful if there were ever more than 600 people living there.

Every building in the town was wooden and as the town died, Barber said, people took the wood with them. What wasn’t taken, has been swallowed by the swamp. Except for the generating plant and pulp mill, there is almost no evidence it ever existed.

It’s doubtful if Buffalo City would have survived no matter what. It was becoming harder to find good quality trees to harvest immediately after the first World War, then the country went into a recession.

The recession “was very severe and lasted a long time for the lumber industry … over 18 months, and it put a lot of people out of business,” Barber told Coastal Review. “Then by 1920, there was a lot of lumber coming in from the Pacific Northwest … because of the improvements in the railroad.”

By June 1920, the proceeds of the Dare Lumber Co., the company that owned the timber rights to the land, were being sold off. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. bought everything for $900,000.

The reason an insurance company paid the equivalent of $14.7 million in modern dollars for 167,000 acres of swamp is the final, unseemly chapter in the story of what really happened to Buffalo City.

In 1912 there were two lumbering companies operating on the Dare County mainland: East Lake Lumber and Dare Lumber Co. With quality timber getting harder to find, both were ready to get out of the business and agreed to a joint sale of the companies to single buyer.

What would become one of the largest life insurance company scams in U.S. history began with George Montgomery of Jacksonville, Florida, who offered to purchase the companies on what was known as an operating contract. Under the proposed deal, Montgomery would manage the companies and, over time, purchase them using the proceeds.

The offer was rejected.

Undaunted, Montgomery offered a New York City apartment building as collateral and some cash — also rejected.

He then moved to New York City and partnered with New York attorney Clarence Birdseye in a scheme that would shake the insurance industry.

Montgomery had been buying shares of Dare Lumber and “On March 26, 1917, George Montgomery bought enough shares of Dare Lumber Company to gain control of the company,” Barber wrote in “Buffalo City and the Blount Patent.”

Now in control of the company, Montgomery and Birdseye immediately turned to also buy East Lake Lumber Co. The combined holdings of the two lumber companies were more than 167,000 acres and covered all of mainland Dare County.

The price for the two companies was $1.1 million. Then on March 28, 1917, Montgomery and Birdseye issued 600 $1,000 bonds — six times the value of what had been paid for Dare Lumber.

March 28, 1917, was an active day for the partners. That was the day they convinced the board of directors of the Pittsburgh Life Insurance and Trust Co. to sell them the company, offering them a price of $80 per share, $15 to $25 more than the going rate.

The agreement was that the board would receive $10 per share upon acceptance of the offer with the balance to be paid later.

The board agreed to the terms and the partners went to a friendly bank, Commercial Trust of New York, where they were given a $120,000 collateral-free loan. The money was deposited in a Pittsburgh bank, the board was paid off, and a new board was installed composed of Montgomery and Birdseye cronies.

What followed was the quick theft of the $24 million, or around $582 million today, in Pittsburgh Life assets with the proceeds deposited with Commercial Trust. There was $379,000 in cash reserves that went to the Commercial Trust account. The Pittsburgh Life board sold the Washington Life Building that the company owned in New York City for almost $4 million. Although Dare Lumber Co. had been purchased for only $1.1 million earlier in the year, the Pittsburgh Life board accepted a $3 million mortgage on the property.

It was during this time the generating site and pulp mill were built at Buffalo City. Barber noted when looking at the ruins that the partners needed to show something tangible, that there was at least some investment in their properties.

“The problem was keeping both Dare Lumber and Pittsburgh Life solvent for long enough to avoid scrutiny of financial regulators,” Barber wrote in his book.

But the stripping of Pittsburgh Life’s assets was so rapacious and swift that in less than two months the company was insolvent and forced to declare bankruptcy.

Financial regulators reacted quickly with investigations into Birdseye and Montgomery making national news. Referencing the reports, New York City District Attorney Edward Swann planned to investigate what happened, according to the May 3, 1917, New York Tribune story with the headline, “Swann Probes Purchase of Insurance Company.”

The reporting included a statement from Jesse Phillips, superintendent of the New York Insurance Department, describing what his department had found.

“No funds were used for the purchase of the capital stock of the company or for the acquisition of the lumber company except what was the assets of the lumber company,” Phillips told the paper.

It took almost two years for the case to go to trial, but according to a Nov. 22, 1919, New York Times article, the Nov. 21 jury reached guilty verdicts.

“Clarence F. Birdseye, Kellogg Birdseye (Clarence Birdseye’s son) and George F. Montgomery, all of New York, who were placed on trial in criminal court before Judge Ambrose B. Reid on Nov. 10, charged with conspiring to defraud the stockholders and policy holders of the Pittsburgh Life and Trust, and with wrecking that organization, were found guilty as indicted today,” the Times reported.

Metropolitan Life’s purchase of the land and everything else Birdseye and Montgomery had owned, including a sawmill in Elizabeth City, may have been as much self-preservation as it was investment strategy. Pittsburgh Life at that time was one of the largest life insurance companies in the nation.

“MetLife bailed them out, just to keep the life insurance business alive,” Barber said.

For Buffalo City, the end was slow in coming but inevitable. Metropolitan Life sold Dare Lumber Co. to the Dare Corp. of Dover, Delaware, in January 1940. Dare Corp. had hoped to use lumbering as a way to finance developing farmland in the vast holding.

Much of mainland Dare is swamp and unsuitable for farming, and that disadvantage was compounded by a nonexistent transportation network. There were no roads connecting mainland Dare with the outside world in 1940.

“The lack of roads could only be remedied with a massive amount of capital investment dedicated to developing a basic infrastructure,” Barber wrote.

In May of 1954 the Coastland Times reported the final curtain for Buffalo City under the headline “Cedar Mill at Buffalo City Finishing Work.”

“The Buffalo Cedar Mill, which has been operating from Buffalo City since 1949, has about two weeks of work left before their operations will be completed,” the newspaper reported. “At that time, it is reported by C. C. Duvall, the company will move their operations to Lake Drummond in the Dismal Swamp … This takes away from Buffalo City the last of the big milling businesses.”