First of two parts

In 1972, between 50 and 100 people called the Currituck Banks home. The actual number isn’t important. It could have been a little more or even a little less. The point is no one really knew or cared. The miles of scrubby sand dunes, low-lying interior flats, and sprawling brackish marsh was largely empty except for birds and fish, and that was how the natives preferred it.

Supporter Spotlight

That it couldn’t stay unspoiled was more or less a given. Currituck, a poor, centuries-old economy based on agriculture, needed money, and developing its 23 miles of unspoiled oceanfront seemed to be the answer. Developers had already purchased thousands of acres and were busy laying out designs for resorts from Duck to Corolla. The county had a rough plan to manage what was coming but needed time and help to pull it off. It was, in a way, an existential moment. No less than the future of the Currituck Banks, so bright yet also so perilous, stood in the balance.

One night that year, Earl Slick, a multimillionaire developer from Winston-Salem, took a surprising phone call from a Currituck duck hunting guide. Carl P. White knew every inch of the sound, sure. But more than that he was a savvy investor who listened closely to the wealthy industrialists who hunted the Banks and used that knowledge to buy stocks and land. A few years earlier, White had steered Slick to purchase the Narrows Island Club, a 1,000-acre strip of rich mainland marsh south of Poplar Branch Landing. Now, White proposed another deal. The longtime owners of the Pine Island Hunt Club, the Barney family from Hartford, Connecticut, were looking for a buyer. The property included nearly five miles of unblemished marsh and oceanfront stretching from the Dare County border north.

Slick knew the property. He had been a guest at the club and enjoyed shooting there. But he already owned The Narrows and planned to build a larger, more accommodating family lodge there. His answer was no. Still, the idea of owning Pine Island nagged at him and over the course of several days, Slick found himself wavering back and forth. Finally, he asked White to find out how much the Widow Barney wanted.

Slick’s decision would have an outsized impact on the future direction of the Currituck Banks, both dramatically preserving and altering its landscape, reshaping the architecture, even helping to shift the economics from an economy based on second homes to an investment-driven market. Not that many of the visitors teeming onto the Northern Banks would recognize these impacts. Most have never heard of Earl Slick or know his history. And for Slick, who died in 2007 at the age of 86, that would have been just fine.

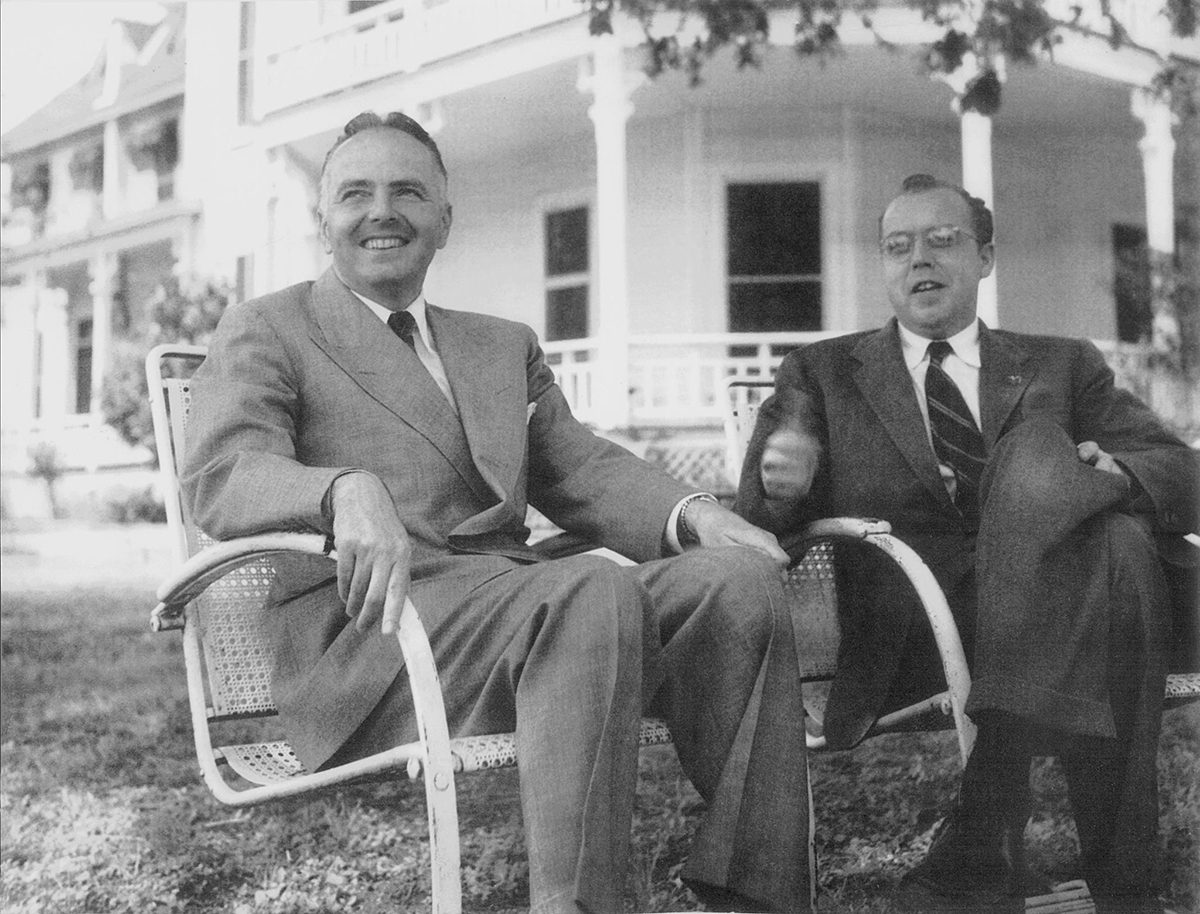

When asked his profession, Slick jokingly called himself a “dog-trainer.” Yet here was a maverick, instinctual investor who owned airlines, cattle farms, wineries, and television stations, among his many and varied interests. And while Slick rarely sought publicity, he built two of the most talked-about resorts on the Currituck Banks – Sanderling, a rustic, nature-themed community, and the sprawling Pine Island resort, with more than 300 luxury-styled beach mansions. In a way, Earl Slick’s story mirrors the larger, complicated story of the Banks themselves, a mix of breathtaking natural reserves, waterways and maritime forests, interposed with a conveyor belt of ever-larger, more exclusive vacation resorts — a cultural and environmental drift that has been playing out now for decades.

Supporter Spotlight

~

Earl Frates Slick was born in 1920 in western Pennsylvania but grew up in Oklahoma City, where his father moved the family to hunt for oil. Tom Baker Slick was a man of the American moment: independent, hard-charging, seemingly tireless. But he was so luckless at first, locals took to calling him “Dry Hole Slick.” That changed in a heartbeat when Tom B. struck oil at the No. 4 Eakin well, producing 10,000 barrels a day. Another well produced a staggering 43,000 barrels a day. Soon, the same locals were calling Tom B. the luckiest wildcatter around — hell, “The King of all wildcatters,” the most famous wildcatter in the world!

Money spilled all around. Millions and millions of dollars. Earl and his older brother, Tom Jr., grew up in wealth and privilege, boarding at Exeter and attending Yale, with a $10,000-a-year living stipend. But life wasn’t always easy. They lost their father to a stroke at the age of 46. The boys were only 14 and 10. Their mother remarried Tom B.’s partner, Charles Urschel, who continued running the oil business. Years later, Tom Jr., considered a brilliantly esoteric student, became obsessed with hunting the Yeti. He, too, died at 46 when a plane he was piloting crashed returning from a Canadian adventure. Those who knew Earl Slick said he was haunted by the deaths and worried that he was destined to die young as well.

After Yale, Slick flew cargo transports in the war and saw the business possibilities of using planes to haul food and cargo from coast to coast. Shortly after being discharged, in December 1945, he learned that the military planned to auction nine surplus Army Curtus Commandos and headed to Washington. According to a short profile in Time Magazine, he walked into the surplus plane division at 1 p.m. and came out 15 minutes later owning the planes. “After that, things really began to move fast,” he told the reporter.

Slick was all of 25. Clearly, he wouldn’t have been able to buy the planes, which cost $247,000, without family money. Yet, like his father, he was relentless, impatient, and endlessly creative. Over the years, he would build Slick Airways into one of the two-largest air transport businesses in the nation, hauling fresh fruit and vegetables in refrigerated cargo planes from California to the East Coast, later contracting to transport military equipment back and forth to Southeast Asia.

While building Slick Airways, Earl was also on the prowl for other business opportunities. In 1948, he sold two cotton ranches to Lloyd Bentsen Sr., father of the future U.S. senator and candidate for vice president. He also bought a 16,000-acre quail-hunting farm, Mossy Dell, in Georgia, where the boyishly handsome six-footer would shoot from the saddle, and invested in a sprawling cattle ranch in southwestern Australia with the television host Art Linkletter and other celebrities. In time, he would expand into commercial real estate development, building one of the first Thruway Shopping Centers in North Carolina, invest in a vineyard, renovate historic buildings, buy stakes in radio and television stations, build nursing homes, fund a Formula 1 racing team, Slick Racers Inc., collect expensive artwork, and exhibit show horses, including Beau Black, a solid black gelding that, according to newspaper stories, “seldom tasted defeat in the show ring.”

“Earl loved the adventure,” recalled Paul Mickey Jr., an attorney and family friend. “I think he kind of liked the life of Ernest Hemingway. I never got the sense he was a deep thinker so much as a resourceful, canny businessman. Whenever I saw him, he was in fatigues. He was a sportsman.”

In 1952, Earl moved the operations of Slick Airways to Los Angeles while relocating his family to Winston-Salem, a small but prosperous center of textile and tobacco industries. William E. Hollan Jr., a family friend and longtime business colleague, explained that it was probably so Slick could be closer to Washington, D.C., where he and his air transport business were represented by the powerful regulatory law firm, Steptoe & Johnson. “This was before jets. It was propeller-driven planes … and it was a long flight from San Antonio to Washington. Winston-Salem was a lot closer. He could get up and back in a day,” Hollan said.

Slick also liked the close-knit, genteel culture of Winston-Salem. He quickly became friends with CEOs from Hanes textiles, Chatham Manufacturing, Reynolds Tobacco, as well as Paul Mickey Sr., a managing partner at Steptoe & Johnson, who also was from Winston-Salem. Earl and his wife Jane built a retreat at Roaring Gap, a small, exclusive mountain resort where corporate elites from Winston-Salem socialized. There, they fell into a comfortable rhythm among a small group of friends who valued their privacy and privilege.

“There was a lot of money, yes,” said Hollan, who acted as a spokesman for the family for this article, “but it was not showy wealth, like the Yankees up North. Earl admired that. There was a lot of Southern charm. It was much more his style of things.”

Earlier in his career, Slick spoke to the press and even seemed to enjoy it. But as he aged, he became more discreet, even publicity shy. Pictures rarely appeared in the papers and he avoided interviews. His philanthropy, often generous, wasn’t broadcast. When different rumors and stories circulated, he instructed his employees not to respond. A code of behavior was evolving. His approach extended to hunting on the Currituck Banks, which Slick first appears to have visited in 1952 as a guest of Steptoe & Johnson. When he purchased his own club and had guests down, they discovered there were strict rules. Guests never shot before dawn and once they were given a blind, they weren’t allowed to change. They were provided one box of shells – always copper, never lead because lead was poisonous – and when they were gone, that was it. For Slick, hunting was about the experience and the camaraderie, not how many birds a hunter put in his bag.

There is another possible explanation for Slick’s penchant for privacy. In the 1930s, his stepfather Charles Urschel was kidnapped from their Oklahoma City mansion while playing bridge with friends. The kidnappers were led by the infamous George “Machine Gun” Kelly and his wife Kathryn. Urschel was returned home after nine days. But the family was never the same, withdrawing from public life and hiring armed guards to surround their house.

Now, as he debated whether to buy the Pine Island Club, Slick wavered between his roles as a conservationist who loved the outdoors, and as a developer who made millions buying and selling land. How could he balance these seemingly opposing forces? Should he even try? Or should he just walk away from the deal?

Next in the series: The story of Pine Island