Disclosure: Coastal Review correspondent Kip Tabb also serves on an informal citizens advisory board for the Outer Banks Field Site.

WANCHESE — Artificial light at night did not adversely affect sea turtle nesting north of Oregon Inlet from 2014 to 2022, undergraduate students found this fall during a four-month study.

Supporter Spotlight

A University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Institute for the Environment program, the semester-long Outer Banks Field Site combines environmental research and community engagement into the collaborative capstone research project. Coastal Studies Institute, a multi-institutional research partnership, and the East Carolina University Outer Banks Campus, host the program.

In addition to measuring the affect of artificial light, which they call ALAN, on sea turtle nesting, the students examined what the public thinks about artificial light at night.

The students presented their findings Dec. 12 during the monthly “Science on the Sound” program on campus.

Senior Drew Huffman, in introducing the study, noted that artificial light at night studies are often focused on inland areas, rather than shorelines.

“There’s a scarcity of existing literature on artificial light at night and coastal systems, as opposed to what we know about more terrestrial systems,” he said. Adding that’s another aim of their research, “to try to expand that knowledge so that we have of a grasp of what things are like for coastal systems and artificial light at night.”

Supporter Spotlight

Numerous studies show a repeated pattern of sea turtle hatchlings crawling toward artificial light, such as a street light, rather than toward the ocean.

The students wanted to gauge the effects of artificial light on nesting.

“Is there a relationship between sea turtle nesting and artificial light at night across the Outer Banks over the last nine years? And if so, what is it?” Those were the questions senior Laura Montague posed in describing the study.

The study area extended north from the north side of Oregon Inlet to the north end of Corolla, but did not include Carova, because, as one student explained, no one had a four-wheel-drive vehicle able to navigate the oceanfront area with no paved roads.

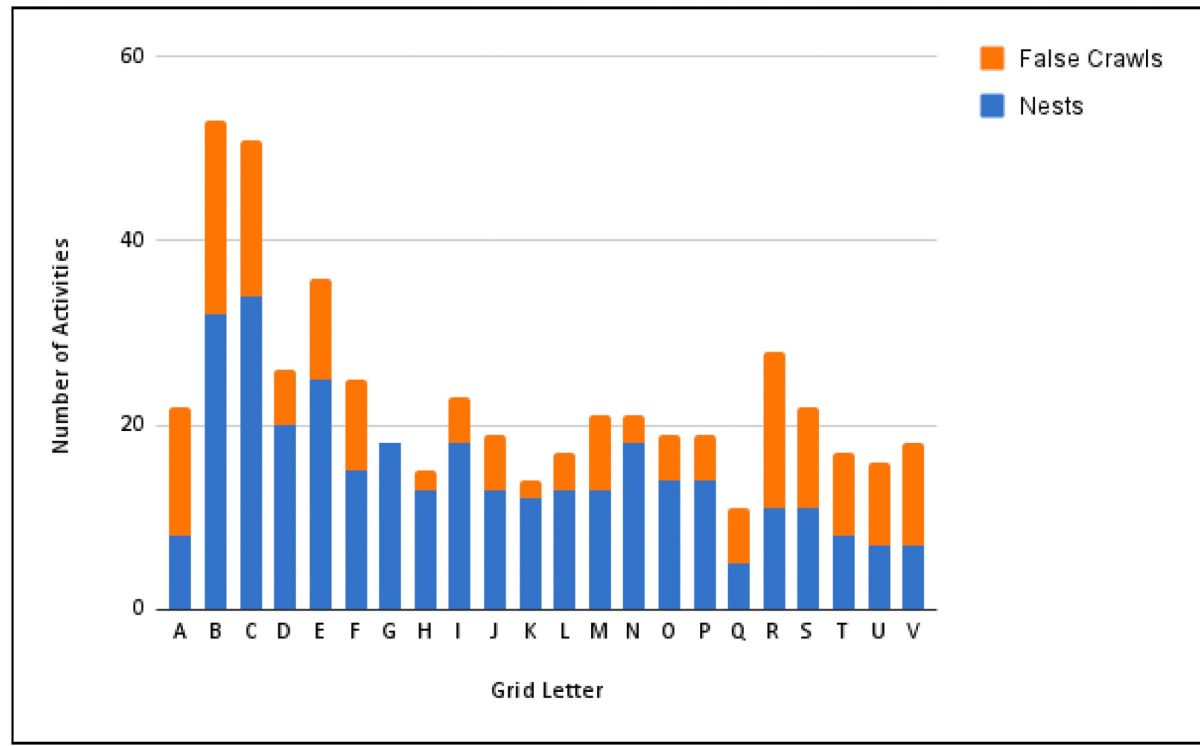

Reported sea turtle nesting data from 2014 to 2022 shows a trend of increasing nesting activity, although overall activity, including false crawls and nests laid, fluctuated during that period, the students found.

During that period, activity hit a low point in 2017 where only about 35 active sites were reported, comparted to 100 active sites in 2022.

“False crawls refer to instances when a female sea turtle comes ashore on a beach but instead of nesting, turns back around to re-enter the ocean,” according to the paper.

Although there was no clear reason for the trend toward more activity, junior Kenza Hessini-Arandel told the audience that she and the other students felt conservation efforts could account for the increase in activity.

“(The) Endangered Species Act that protected a lot of these species and also management efforts that organizations like (the Network for Endangered Sea Turtles) and the National Park Service perhaps helped increase the number of turtles that we’re seeing along the coast,” she said.

There was at least one anomaly in sea turtle activity that the students could not explain.

The Outer Banks is at the north end of the range where sea turtles nest, and Corolla, at the north end of the study area, saw significantly less nesting activity than sites at the south end near Oregon Inlet, which is considered to be a more compatible nesting area for turtles.

Though the number of Corolla nesting sites was significantly less than those on the south end of the study area, the number of false crawls was the same there as areas where activity was greater, representing a much higher percentage of false crawls compared to nests.

“However, we do not see the same pattern when looking at false crawls; there seem to be more false crawls in the northernmost and southernmost areas compared with areas in between,” the paper noted.

“There are a lot of variables that come into play with false crawls and we don’t know exactly why we are seeing this trend,” Hessini-Arandel said.

The students included environmental research in the study, as well. They explored the social science of artificial light, whether people attach significance to artificial light, and their perception of how it affects the environment.

The public perception survey included about 500 responses, with respondents divided into residents, seasonal residents and visitors.

The students found a strong indication that the public perception is that artificial light has a significant impact on the environment, and regardless of age or sex, or even where people lived, they were concerned about the effect.

Although there were small variations in the degree of concern among the groups, the overall response showed a clear level of unease with the amount of artificial light on the Outer Banks.

Junior Julie Yakaboski noted that a significant majority of people said they were either concerned or very concerned.

“Taking these two together, that’s about 70% of our responses,” she said.

Significantly, almost no one – fewer than 5% — said they were “not concerned about it at all.”

That attitude appears to correlate closely with whether respondents felt artificial light should be reduced. Asked whether they felt artificial light on the Outer Banks should be reduced, 90% of respondents said they either agreed or agreed strongly. More than 60% said they “agreed strongly.”

Because of the timing of the recent survey, answers were somewhat skewed by the number of full-time and seasonal residents, students said. However, the results would seem to indicate there is support for local governments to implement regulations or ordinances controlling artificial light.

“Public perceptions of ALAN have the power to affect the development of policies that regulate it,” according to the paper.