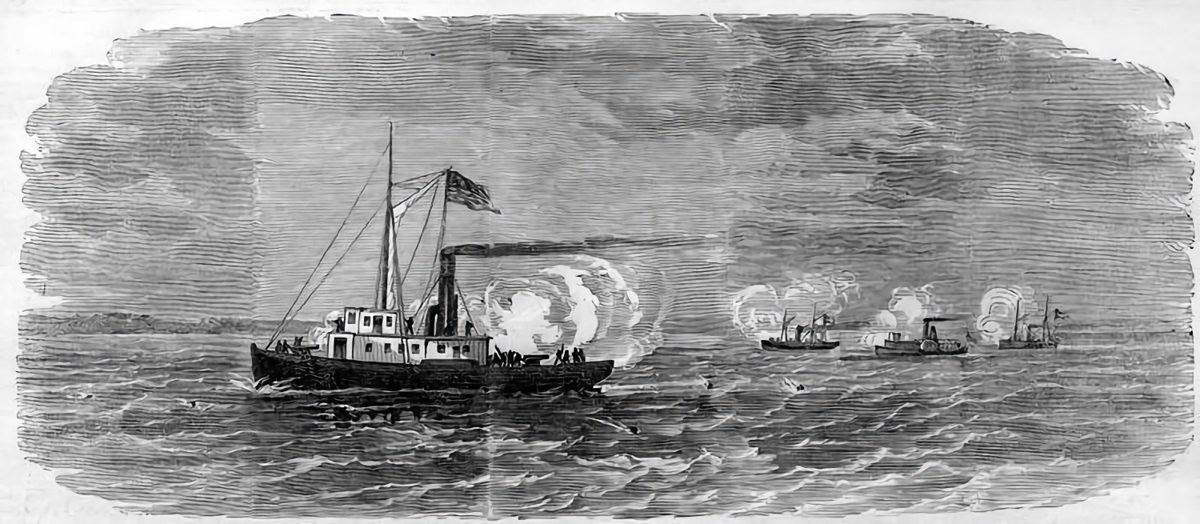

As the overwhelming firepower of the 40 boats of the Union Navy in the Roanoke Sound approached Feb. 10, 1862, Midshipman J.L. Tayloe, captain of the CSS Fanny, left his command and blew up the ship at Cobb Point, just south of Elizabeth City.

It was an ignominious end to a small but valiant vessel that had served forces on both sides of the Civil War.

Supporter Spotlight

Fanny’s time with Southern forces was short-lived. The ship had been captured by Confederate forces mere months before on Oct. 4, 1861, at Loggerhead Inlet, a now-dry strand of beach about a mile north of Rodanthe.

At the time, Union forces had secured their first significant victory of the Civil War when they wrested Hatteras and Ocracoke inlets from Confederate control in late August 1861.

Soon after securing the inlets, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, who led the expedition, returned to his headquarters at Fort Monroe, leaving command of the Hatteras garrison in the hands of Col. Rush Hawkins, commander of the 9th New York Zouaves.

By late September, it was apparent that Confederate forces were growing in number on Roanoke Island. Writing in his 2018 East Carolina University master’s thesis, “Detecting Archeological Signatures in Shallow Water: A study of the Chicamacomico Races,” James Kinsella describes Hawkins’ reaction to the news that enemy troop strength had increased to his north.

“In response to the capture of Hatteras and Ocracoke Inlets, the Confederate Army sent reinforcements to Roanoke Island. Hawkins, hoping to counter the threat from the north, sent the 20th Indiana Regiment to Chicamacomico (Rodanthe) to counter the move,” he writes.

Supporter Spotlight

The plan to move the regiment 40 miles north to what the documents of the time referred to as Loggerhead Inlet was flawed. The USS Spaulding, a troop transport ship, was given the task of moving the regiment. But the Spaulding’s draft was too deep for Pamlico Sound and most of the men had to be transferred to smaller vessels. Although the men were transferred, the supplies they needed to operate 40 miles from their own lines did not go with them.

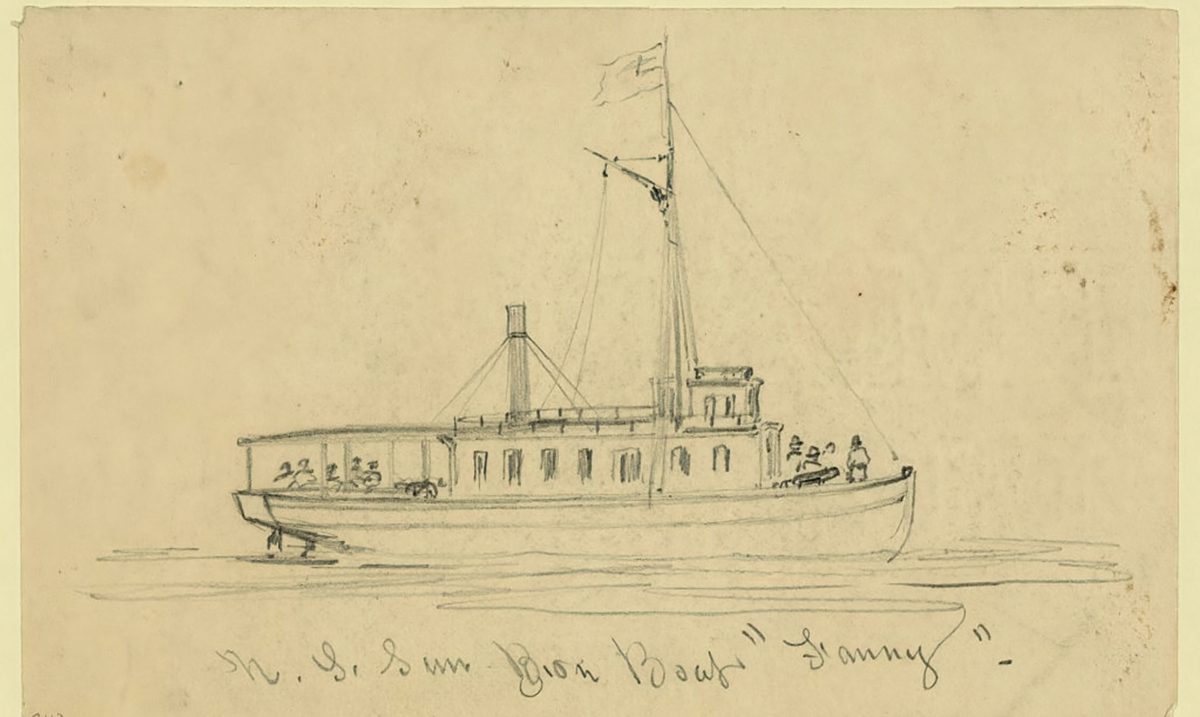

“Three armed steamers (the Fanny, the General Putnam and the Ceres) were ordered to take them from Hatteras to Chicamacomico. All but 75 men were transferred to the armed steamers. They arrived at Chicamacomico with few tents and only two days’ food and supplies,” Kinsella wrote.

Hoping to quickly resupply the Indiana Regiment, the Fanny was rapidly loaded with supplies – food, ammunition, medicine and clothing – and sent to Chicamacomico.

“I left in the steamer Fanny at 6 a.m. for Chickamicomico or Logger Head Inlet arriving there at 1 p.m. We anchored in about 8 feet of water and waited there two hours and a half before we got communication from shore,” the civilian captain of the Fanny, Master J..H. Morrison, wrote to Gideon Wells, Secretary of the Navy.

That two-and-a-half-hour delay in unloading the Fanny was critical and may ultimately have been the reason Confederate forces were able to capture the vessel.

Christopher Olson, in his April 2006 article, “The Curlew: The Life and Death of a North Carolina Steamboat, 1856-1862 ” written for the North Carolina Historical Review, describes the reaction to the Fanny on Roanoke Island.

“Word of the Union steamer’s appearance reached the Confederate commanders at Roanoke Island. After loading 150 men of the Third Georgia Regiment on the Curlew and two other Confederate gunboats, the fleet sailed against the Union outpost. The Confederate fleet surprised the Fanny at anchor at 4:00 P.M,” he wrote.

Under the command of Commodore William F. Lynch, the three boats of the Confederate fleet, the CSS Curlew, Raleigh, and Junaluski, moved quickly into position.

“The Curlew arrived first and steered to cut off any escape attempt,” Olson wrote.

On the Fanny, the 20th Indiana had finally made it to the boat and had just taken off the first load of provisions when the enemy fleet was first seen.

“When the boat had shoved off and got about two thirds of the way on shore we saw a steamboat to the westward about 4 p.m which proved to be one of the enemy. She was standing to cut off our retreat and in a short time two more appeared steering directly for us. The first one then stood in and commenced firing upon us and as soon as the other two came up they did the same,” Morrison wrote to Wells.

Leased for service in the war by the federal government, the Fanny was no warship, as Morrison recounted in a letter published in the Oct. 18, 1861, edition of the Cincinnati Daily Press.

“The powder I had on freight was stored in a house on deck forward of the boiler, and a shell exploding into it would have blown the vessel to atoms. Besides this, my boiler was on deck and insufficiently protected against shot from cannon,” he wrote.

There were other problems as well.

“Sending supplies aboard Fanny was a risky venture as there was a shortage of capable navy men and officers,” Kinsella notes.

That shortage led to the Fanny being crewed by Army personnel who were unfamiliar with the armament on board, as Morrison’s letter in the Daily Press made clear.

“The gun crew knew nothing of gunnery, and I think the Indiana troops on board knew little better,” he wrote.

The commanding Union officer on the boat was Quartermaster Isaac Hart of the 20th Indiana Regiment, who had made the decision to surrender, according to Morrison. As that decision was being made, there seems to have been considerable confusion onboard the Fanny.

“The mate of the boat and a few soldiers turned to and threw over board some thirty cases of ammunition and Captain Hart forbade them to throw any more overboard. We likewise requested the sergeant major to throw the cannon overboard which he refused to do saying it would be worse for them if they were taken prisoners,” Morrison told Wells.

Hart ordered the boat run aground and by 5 p.m., the Fanny was in Confederate hands with most of the crew prisoners. Morrison and his first mate, who were civilian employees of the U.S. Navy, escaped in a skiff. Also on the skiff was Morrison’s son, who was, Morrison wrote, ill and in his berth at the time of the attack. There were no casualties in the engagement.

In his report to Wells, Morrison was critical of the slow response of the 20th Indiana, writing, “… they had plenty of time from our arrival to that of the enemy’s boats to have got everything on shore from the Fanny…”

In his letter published in the Daily Press he was even more critical.

“We had enough time from one o’clock to half-past four to have discharged every portion of the cargo of the Fanny … had we received assistance from the Indianians on shore. I cannot but feel that it was their neglect to assist us that the loss of the Fanny may be attributed,” he wrote.

The slow response of the Indiana regiment to unload its supplies is but one part of a larger picture leading to the capture of the boat.

The USS General Putnam was a 103-foot, sidewheel gunboat that met the Fanny off Loggerhead Inlet. One of the Fanny’s guns was transferred to the Putnam, evidently because the Putnam was part of the Croatan Sound blockade force.

“Fanny was at a further disadvantage as its Sawyer gun was transferred to the USS General Putnam. General Putnam was ordered to stay in Croatan Sound to enforce a blockade, leaving Fanny vulnerable and without naval support,” Kinsella wrote.

But according to the report by Cmdr. S.C. Rowan, captain of the sloop of war USS Pawnee, the Fanny should never have been left alone.

“The Putnam, that should have been there to give countenance and support to these panic stricken people, left her station on the arrival of the Fanny and arrived at the bulkhead at sundown the same evening where she grounded for the night. I asked Captain Hotchkiss why he left without orders. He replied that he came down for coal. I told him he could have obtained coal from the Fanny,” he wrote.

Precursor to modern aircraft carrier

If the capture of the USS Fanny was perhaps inglorious, it stands in contrast to its earlier service in the war.

The Fanny could be the first true precursor to the modern aircraft carrier.

Writing for the U.S. Naval Institute, W.T. Adams, in his article “The Birth of the Aircraft Carrier,” suggests the Fanny may hold the distinction of being the first watercraft to serve as a platform for aerial observation of the enemy.

“The veteran and daring balloonist J. LaMountain has been at Fortress Monroe making ascensions and examinations of the secessionists’ positions in that vicinity. On the 3rd instant he tried a new scheme in aerial scouting, by taking his balloon on board of the steamboat Fanny, and went out in the middle of the river ascended 2,000 feet, with the balloon secured by a rope to a windlass,” Adams wrote.

There is one more twist to the story. According to Morrison, the Fanny that the Confederacy captured was not the original Fanny that the U.S. Navy had leased.

He writes that after “… various expeditions … she became disabled and her crew was transferred to the P.T. Hart. As it was advisable to retain the prestige of the Fanny’s name, the sign upon her stern was transferred to the P.T. Hart. and she afterward sailed under the name of the Fanny — so in reality it was the P.T. Hart, and not the Fanny that was captured.”