Last in a series.

The week after Hurricane Florence devastated eastern North Carolina in September 2018, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center Executive Director Karen Willis Amspacher wrote in an online message to members and patrons that throughout the 13 unincorporated communities making up Down East and the entire county, “we’ve been putting back the pieces.”

Supporter Spotlight

But “in the midst of the damage and pain throughout Down East, the Museum has suffered far more damage than originally seen.” She continued that there were significant leaks in the facility, mold was growing on the carpet, floors were buckling and drywall was crumbling.

By mid-October 2018, teams and equipment had been brought in to help manage moisture, and staff and volunteers had completely emptied the nearly destroyed building so the damaged floors, walls and roof could be replaced, Coastal Review reported at the time. The museum reopened May 2020, after the $3.4 million in repairs were completed.

Hurricane Florence’s impact on Down East initially grabbed the attention of researchers, agencies, educators, students, advocates and others invested in adaptation and resilience, leading to research on ghost forests, sea level rise, inundation and flooding. They’ve formed the Down East Resilience Network to raise awareness and create a better understanding of the environmental changes to the area and find solutions.

As part of that awareness effort, the network hosted a two-day community conversation Sept. 12-13 at the museum on Harkers Island to discuss Down East since the 2018 Category 1 storm and how to prepare better for “the next Florence.”

Over the course of the two-day conversation, attendees were given tours of Cape Lookout National Seashore and Down East communities, they heard the science behind ghost forests and king tides, had discussions with representatives from the North Carolina departments of transportation and insurance, and area utilities.

Supporter Spotlight

There also was time for residents to voice their concerns including the everyday flooding plaguing Down East, the poorly maintained ditches throughout the area, and frustrations with new development.

Upgrading transportation infrastructure

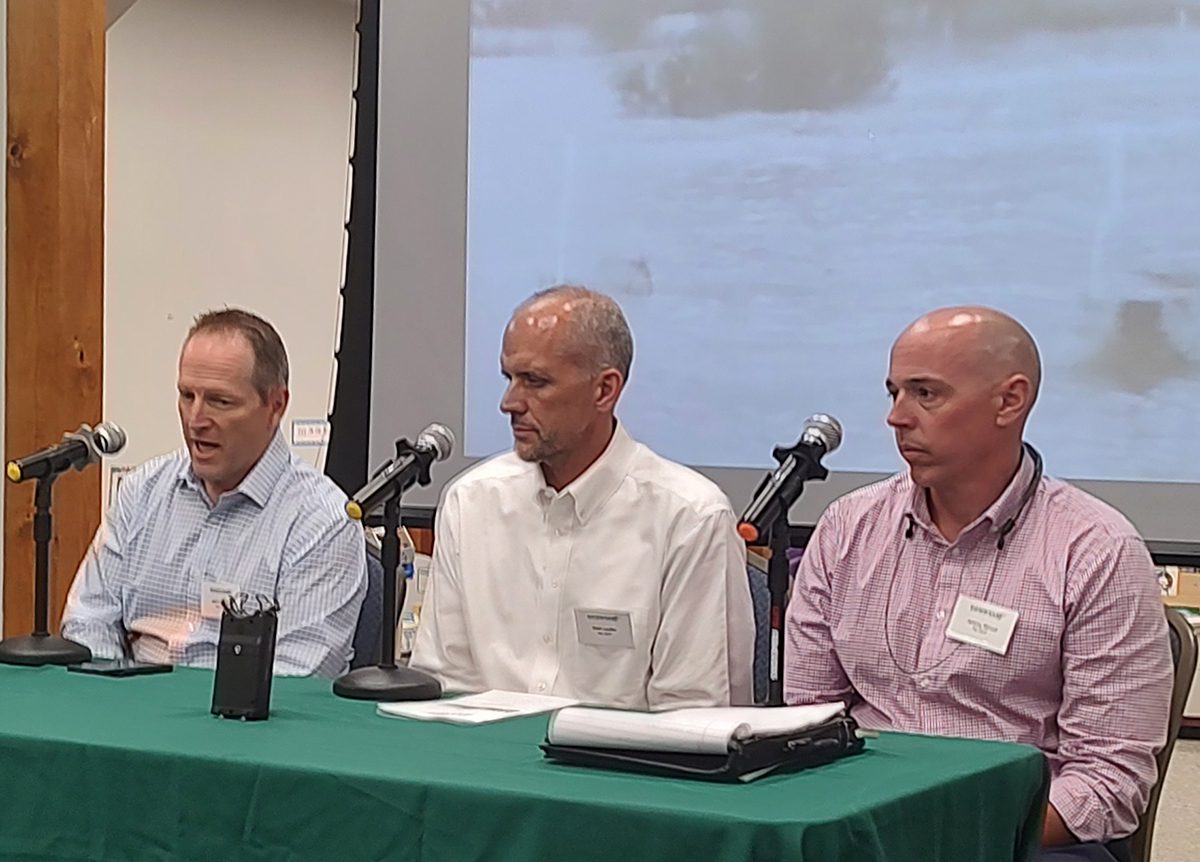

Department of Transportation Assistant State Hydraulic Engineer Matt Lauffer, Division 2 Engineer Jeff Cabaniss and Division 2 Deputy Engineer Jeremy Stroud explained during the conversation that the state agency is preparing for climate-related change.

Division 2 is responsible for eight counties, including Carteret, and manages preconstruction, planning and construction, and maintenance of roads, bridges and ditches and culverts along state routes.

Cabaniss said the agency is one of the largest landowners in the state because it owns rights of way.

NCDOT’s responsibility when it comes to drainage is two fold, he continued. First is to keep water off the road if possible and the other is to divert through pipes, culverts and bridges the water that is coming.

Since the department owns facilities in all communities, as communities face issues with flooding, so does NCDOT. “A lot of times, we have the ditches alongside the road. We can clean those out, but we can’t make (the water) go away from the road because that goes off the right of way. And we don’t have the permission, the funds or the people to make that happen,” he said.

NCDOT removes debris from the roadways and to restore the network after emergencies and other catastrophic events, Stroud added.

But not all ditches are state-maintained, especially Down East where artificial drainage can also funnel water onto land as well as roadways.

To prepare for how environmental changes will affect transportation infrastructure, Lauffer said NCDOT is working with climate scientists to design projects that consider more hurricane surge and sea level rise, and the implications of those on a proposed facility, such as an interstate. Planners are also beginning to incorporate resilience methodology in new projects.

“We’re definitely looking at the hazards that can adversely affect that facility,” he said, and how to best design projects.

The agency is using past flooding data for vulnerability assessments. An assessment that is nearly complete is for U.S. Highway 70 between the state ferry terminal at Cedar Island and Raleigh that will look at the vulnerability of that major corridor.

Cabaniss said that, on the maintenance side, NCDOT is replacing older, smaller drainage pipes. Recently, a 24-inch pipe in Davis was replaced with a 55-inch by 72-inch pipe.

Stroud added that they get recommendations from the hydraulic unit for every pipe that is replaced, a requirement now for projects that receive federal funding.

“If we have future events, we can show that we brought it up to the current standards,” he said. “Hopefully there is no damage to that structure, and even if there is, it’s not because we put an inadequate pipe size in that would not meet the criteria for that event.”

Lauffer said that after Hurricane Florence, there was a huge realization that NCDOT could do better to know what to expect during major storms and how they affect the larger transportation network.

To do that, NCDOT has partnered with other state agencies and researchers who have tools and programs in place to measure flooding across the state, like the Flood Inundation Alert Network. NCDOT is using that data to project what roadways could be inundated based on the forecast for a particular storm. The agency also has a system that continually monitors 15,800 major bridge structures and culverts statewide.

“We have a better understanding of the vulnerability of our facilities and structures,” Lauffer said, which they’re trying to get a better handle on “so that we can potentially recover faster, respond better, and potentially save lives by knowing these things are coming.”

Girding utilities

Heidi Smith, manager of energy services and corporate communications with Tideland Electric Membership Corp., which serves parts or all of Beaufort, Craven, Dare, Hyde, Martin and Pamlico counties, and Ethan Horne, field engineer with Carteret-Craven Electric Cooperative’s resilience planning, both said the utilities they represent are working to prepare smarter.

“We’ve just obviously had a lot of hurricanes. Practice doesn’t necessarily make perfect, but you get smarter and smarter each time around, there’s always lessons to be learned,” Smith said.

Horne said that flooding is always a big issue, especially because it makes reaching lines when they’re down more dangerous and difficult, but Carteret-Craven Electric Co-op is going to be better with the next Florence, starting with upgrades to the main office in Newport.

A new fuel system that holds 10,000 gallons of diesel, a new radio tower for better communications, “because we always have problems communicating from Newport down to Cedar Island, Harkers Island area, especially when the towers are down,” he said. The co-op is working on improving response to outages, putting in a new substation in Otway, upgrading lines, and talking about bringing in different contractors with specialized equipment for hurricane response.

Smith said there’s a lot of challenges for underground infrastructure, including inundation, falling limbs and trees in ghost forests, and fires that burn and burn for months, especially for places like mainland Hyde County that are losing population.

There’s so much technology, but “Here’s what I’m going to tell you, you’ve got to be prepared. We’re getting people back on faster than ever before. Our lives are more electrified, it is more inconvenient but what is shocking,” she said, is that in her 31 years with the utility, she’s seen a lot of hurricanes, but during Hurricane Florence, she saw communities flood that had never been flooded before.

“When you’ve been flooded before, you’re better prepared than if you haven’t been,” Smith continued. She explained that she witnessed 900 of 2,000 homes in a community flood and “people literally died sooner because of that, because they’ve never been through it before. They didn’t have the mental infrastructure. They didn’t have the physical infrastructure. They didn’t have the family infrastructure –nothing to make them through it. And we’ve got to better prepare people. Because preparation makes us better. Preparation helps us emerge and resume our lives much more quickly. And we’ve got to do it. And we’re going to help lead the way.”

Understanding insurance

Jessica Gibbs, regional director for coastal northeast North Carolina with the state Department of Insurance, said the department has many services and is available to answer any questions.

“We’re there to help you understand it, help you make sure you’re getting exactly what you need, and you’re not being overcharged, and you’re not being double-covered.” She reiterated that experts in the department answer the calls, not a recording. There are also resources on the department’s website to prepare and recover from catastrophic events.

Also with the Department of Insurance, Tim Crawley, consumer complaints analyst, told those in attendance that if you run across issues in making a claim, he’s the person you contact.

Here on the coast, he said during the community conversation, “Most companies will exclude wind and hail, so then you have to chase the wind and hail policy down” and if you have a federally underwritten loan, they’re going to require you to carry flood insurance on your home as well. “Those are the challenges you’re having to face here.”

He added that it’s important to make sure your coverage is in sync with the current real estate market and adequate for your dwelling – don’t just base it on your tax records.

“When a claim is filed for, especially here, you’re having a multifront attack on your property. You’ve got water coming up from the ground to flood, and then you’ve got the wind assault from above,” he said, and the insurance company is going to have to determine how the damage occurred. For example, if the floor or carpeting is soaked, and there’s a saturation line coming up the wall, the insurance company’s going to say that’s flood related and will have to go through the flood policy.

“The home policy is a covered-peril policy,” Crawley said.

That means it only covers those perils that are expressly stated in the policy.

“We all think, well, I have insurance, so I’ve got everything from hurricanes to lightning, to alien invasion, to my kid drawing all over the house with crayons, you know. It is written as a covered-peril policy for a very specific reason,” Crawley said.

Then there’s also the language used in homeowners policies. “It says they will repair or replace. The word ‘repair’ is first for a very specific reason: They’d rather put X-number of shingles on your roof than have to (replace) your entire roof.”

Ryan Cox, president of Insight Planning & Development consultant services, said he defined a natural flood as moving water covering two or more properties, and that could be your property and the road, which is state property. “If the road and your property are flooded, then that is two or more properties, but that is the definition of a natural flood,” he said. “Flood is water moving across the ground, that’s a flood. If it’s from the roof, that’s wind and hail.”

Your insurance agent is also a great resource to find out if you have the right coverage, Crawley added. But, he warned, agents sell policies, they do not adjust claims.

“Once the claim is filed with the insurance company, it’s the adjuster that’s driving the bus at that point,” he said, adding that the agent has to step aside to let the claims organization take over.

Crawley said he tells everybody before any storm that their smartphone is their best tool. He encourages residents to take photos of their insurance policies and expensive or bigger items, like bedroom and living room furniture and electronics, and make sure those are saved in online storage.

“As a former claims adjuster, the easier you make it on the adjuster, the faster you’re going to go through the process,” he said, so have your policy information ready when you file a claim.

Cox added that just because you are not required to have flood insurance, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t get flood insurance. Many residents don’t get flood insurance because they’re not in a special flood hazard area, or 100-year floodplain. A 100-year floodplain means there’s a 1% chance of annual flooding, or a one-in-a-hundred chance every year that an area could flood.

“The gamble is, where is it going to happen? It can happen in the western part of the state for flash flooding. It can happen in the central part of the state through flash flooding or hurricane. It can happen either here from storm surge, or it can happen as a combination of storm surge and riverine flooding,” he said, which is when water from the ocean or sound – storm surge – and riverine flooding meet.

He encourages residents to have flood insurance, whether in a floodplain or not, “the worst is having to tell somebody that there’s nothing I can do for you because you didn’t have flood insurance,” Cox said.

Identifying what’s next

Organizers spent the weeks after the community conversation compiling notes collected during the two days of programming to identify concerns and what actions are needed.

The following are some of the comments provided to and compiled by organizers and shared in a spreadsheet with Coastal Review:

“One person says that recurring flooding Down East is driven not only by sea level rise, but also by poorly maintained ditches – not enough, filled with debris, etc.”

“The tours through Down East communities were eye-opening and having residents leading the way gave me a lot of perspective on the issues they’re facing.”

“I’ll admit that when I first heard about global warming thirty years ago, I thought I’d never live to see it or feel it. Obviously, I was wrong.”

And one comment said the realistic expectation is that it’s not possible to be able “to protect every parcel” but they “don’t have to run for the hills.”

“Environmentalists aren’t going to let us dump [referring to water] into Sound” later goes on to say that she understands that it may impact sea life, but says that “water needs to go.”

The spreadsheet also detailed notes where action was needed, such as Down East needs to look at all the options for community sustainability and have a “seat at the table” when it comes to planning for roads and other infrastructure, and for a readiness, response, recovery plan to work it has to be developed with the community.

Amspacher told Coastal Review after the event that she believed everyone who participated went away feeling that the conversation was positive for all involved.

“The community learned about resources for adapting to the changes, and the researchers and agencies gained a firsthand look at the issues Down East residents live with every day,” she said. “These two days were the beginning of many more conversations that have taken place since this gathering, and more are underway for the immediate and long-term future. Those who helped plan see it as an excellent first step in connecting needs and resources.”

Among those who helped plan the conversation were North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency Resilience Planner Holly White, Western Carolina University geology professor Rob Young, and lifelong Down East resident Chris Yeomans, a retired educator.

White told Coastal Review that resiliency staff attended the recent meetings of community leaders Down East to listen to their concerns about flooding issues and other hazards impacting these areas.

“We want to understand the local perspectives as a continuation of NCORR’s recent community work in the eastern half of the state through a disaster resilience program called RISE. Through hearing the perspectives of those that live in the region, we hope to determine if NCORR or other partners can be helpful in increasing the resiliency of the communities,” White said.

Young, who is director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western, told Coastal Review that he became involved in the network three years ago when he met Amspacher.

She shared with him the issues she saw for Down East and how the unincorporated areas of the counties seem to have trouble getting resilience funding and organizing for projects, “Even though it is clearly one of the most exposed areas to coastal hazards in the state,” he explained.

Areas like Down East have a lot of trouble developing projects and getting resilience funds because it’s not an incorporated municipality. It’s really easy for the state to work with a municipality that has lots of capacity, like planning and GIS departments, “but working with an area that doesn’t have any of that, you have to go through the county. And if the county is either not interested or if the county doesn’t have the capacity, then those folks end up at the end of the line.”

Young said meetings like the community conversation are important “even though we didn’t walk out of there with the projects developed and money on the way” and because the state agency representatives showed up and listened, they were reminded what and where the needs are “because ultimately, they are going to have to drive some of these solutions” by working with county governments.

Yeomans, a retired Carteret County principal, spoke to Coastal Review in a follow-up interview from the front porch of his daughter’s home on Harkers Island that she just purchased. He was helping with odds and ends that needed fixing.

He said he sees how vulnerable Down East is to storms and sea level rise.

“The water is higher than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” he said. Adding it’s the changing environment is just part of nature, “but I think we humans have sped up that process.”

His question, which appears to be on the minds of most Down East residents, is “How can locals maintain their heritage and maintain where they live. Be able to stay here and thrive, too.”

When he was a young boy growing up on Harkers Island, before Down East was “discovered,” he could see development coming. He observed it on the Outer Banks, and knew it was imminent for Down East, he said.

Now, what gets his attention is development in the unincorporated communities, and the associated septic systems and well water, especially in low-lying areas where there’s sea level rise, which is saturating the ground.

When does development maximize our ability to sustain the natural environment and human interaction? He asked. “When do we put up a ‘No Vacancy’ sign? Who’s going to make that decision?”

That concern, Yeomans continued, runs parallel to Down East resilience efforts.

“My heart is Down East. I love the Down East people. I love our culture. And I want to see it protected as much as we can with the changes that are happening,” and those changes need to happen responsibly, and in a way that protects the environment and the Down East heritage, he said.