The total number of Atlantic tropical cyclones that strengthened from weak Category 1 storms into major hurricanes within a 36-hour window has more than doubled in the last 50 years, a new analysis finds.

The observed maximum changes in wind speed for the lifespan of Atlantic tropical cyclones between 1971 and 2020 suggest that the intensification rates of these storms have increased as human-related greenhouse gas emissions warm the planet and oceans, according to the paper, “Observed increases in North Atlantic tropical cyclone peak intensification rates” published Thursday in Scientific Reports.

Supporter Spotlight

Historically, the most damaging tropical cyclones have been the most intense, with the majority undergoing rapid strengthening during their lifecycles.

Hurricanes Sandy in 2012, Irma, Maria and Harvey in 2017, Ida in 2021 and Ian in 2022 were the costliest U.S. weather and climate disasters in the last decade. All similarly strengthened rapidly, with most evolving from tropical storms to Category 3 or greater in under three days.

Because this strengthening can be difficult to predict and forecast, quickly intensifying tropical cyclones can create communication and preparedness challenges for coastal communities in a storm’s path, according to the study.

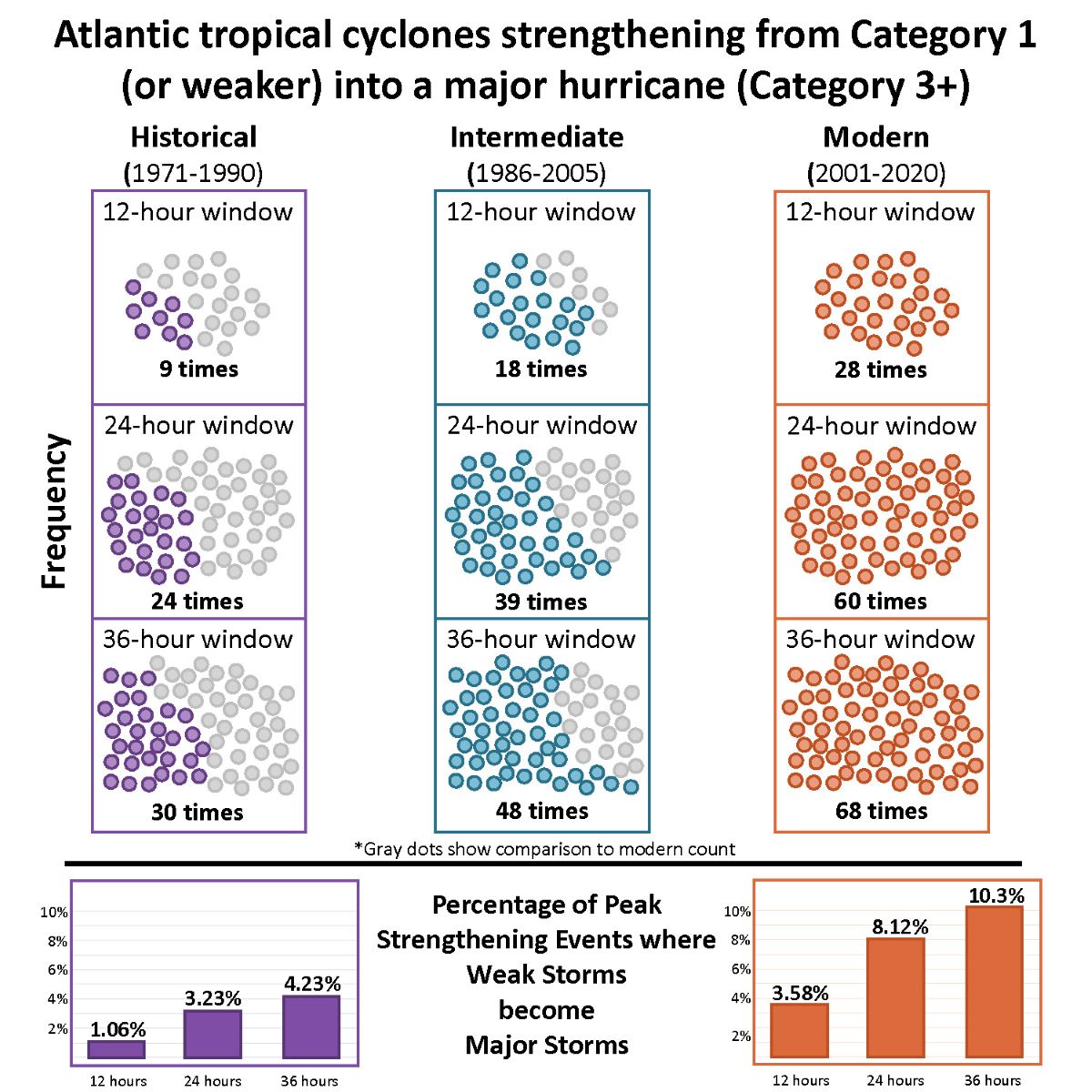

For the analysis, Dr. Andra Garner, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Science at Rowan University in New Jersey, broke the 50 years’ worth of data up into three periods: the historical era, 1971-1990; the intermediate era, 1986-2005; and the modern era, 2001-2020. Maximum intensification rates were calculated for 12-hour, 24-hour and 36-hour windows.

The maximum intensification value of each tropical cyclone was defined for the study as the greatest increase in wind speed across any window of time during the lifespan of the storm.

Supporter Spotlight

Garner found that between 2001 and 2020, average maximum tropical cyclones intensification rates increased 28.7% compared to storms that happened from 1971 to 1990. Additionally, from 2001 to 2020, it became more common for tropical cyclones to intensify most quickly in the central Atlantic off the U.S. Southeast Coast, the southern Caribbean Sea east of Central America, and the southeast Atlantic off the west coast of Africa, compared to storms that took place from 1971 to 1990.

The tropical cyclones that intensify at their fastest rate over the central part of the Atlantic basin could be particularly dangerous for communities along the East Coast, “an area already threatened by other evolving tropical cyclone hazards in a warming world, such as slower-moving tropical cyclones and changing tropical cyclones tracks,” the study says.

Garner told Coastal Review this week that part of her motivation for this work is knowing the fact that ocean surface waters, which are a key fuel source for hurricanes, have warmed substantially in recent years.

She cited the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s documented increases in sea surface temperatures of more than 1 degree Fahrenheit since the 1980s. The IPCC is a United Nations group that assesses science related to climate change.

“Since I knew that ocean waters are a critical component for hurricanes to intensify, and, in particular, for allowing hurricanes to intensify quickly, I wanted to see what kinds of changes might already have occurred in the observational record of Atlantic hurricanes over the past 50 years,” she said.

Garner said that the warm ocean waters are a vital source of fuel for hurricanes to strengthen.

“Think of it like your morning cup of coffee — for a hurricane, warm ocean waters act like the caffeine in our morning coffee that helps get us going. When we have abnormally warm ocean waters, it’s kind of like an extra shot of caffeine in the coffee, providing lots of energy for the storm,” she explained.

Keeping this in mind, and knowing that oceans have absorbed about 90% of the excess warmth human-caused climate change has generated in recent years, she said she set out to understand, broadly, how the intensification rates for Atlantic hurricanes has changed in recent years.

Overall, the fastest average pace at which hurricanes strengthen has indeed significantly increased by more than 25% from 1971-1990 to 2001-2020. Also, during 2001-2020, it was about as likely for hurricanes to intensify by more than 57 mph in just 24 hours as it would have been for hurricanes to intensify by this amount in 36 hours in the historical era, she explained.

These kinds of changes have impacted how common it is for a hurricane to intensify from a fairly weak storm such as a Category 1 hurricane or tropical storm, into a major hurricane of Category 3 or greater.

In particular, between 2001 and 2020, the number of times that hurricanes intensified from weak storms into major hurricanes within 24 hours more than doubled compared to 1971 to 1990, “which is something that my results show would have been statistically impossible to have happen under historical climate conditions,” Garner said.

Her findings didn’t come as a surprise, rather, the analysis serves to quantify the phenomenon of strengthening tropical cyclones that is very much expected in a warmer climate, Garner said. The increased likelihood for hurricanes to transition from weak storms into major hurricanes in 24 hours or fewer was particularly striking, she said.

Garner stressed that her results indicate that there have been changes in areas where hurricanes intensify most quickly, increasing the likelihood of rapid strengthening in several locations, including along the East Coast.

“One of the main reasons these findings matter is that, when storms intensify quickly, they can become more difficult to forecast and to plan for, in terms of emergency action plans for coastal residents. We also know that many of the strongest, most damaging hurricanes do intensify particularly quickly at some point in their lifetime,” Garner explained.

“My work shows that we are already seeing overall increases to the fastest rates at which Atlantic hurricanes intensify, which means that we are likely already seeing an increased risk of hazards for our coastal communities,” she said, “Including, and perhaps especially, those in North Carolina, given that results showed an increased likelihood for hurricanes to intensify most quickly near the U.S. Atlantic Coast. This means that it will be especially important for our coastal communities to work towards enhanced coastal resiliency measures and emergency action plans that may be able to adapt to hurricanes that strengthen more quickly.”

Garner said that her findings should serve as an urgent warning.

“The rates at which hurricanes strengthen — and the frequency with which they transition from relatively weak storms into major hurricanes — has significantly increased in just the last 50 years, over the same time when we see substantial increases to ocean surface temperatures due to human-caused warming,” she said.

“Without major changes in our behavior and a rapid transition away from fossil fuels, this is a trend that will continue to get more extreme,” Garner said. “There is hope — hope that comes from knowing that we are the cause of this problem, so we can also be the solution; hope that we could secure a more sustainable future. But that hope will only be realized if we take the necessary actions to decarbonize our economies.”