Guest commentary

We in the Carolinas share space with a wonderful but imperiled plant, the Venus flytrap.

People everywhere know and love this unique carnivorous plant for its remarkable ability to ensnare insects within toothed, snap-trap leaves with a hair-trigger, allowing them to snap shut around a struggling insect within milliseconds. A century before “Little Shop of Horrors,” Charles Darwin was so enchanted he had collectors send him these “most wonderful” plants for experiments.

Supporter Spotlight

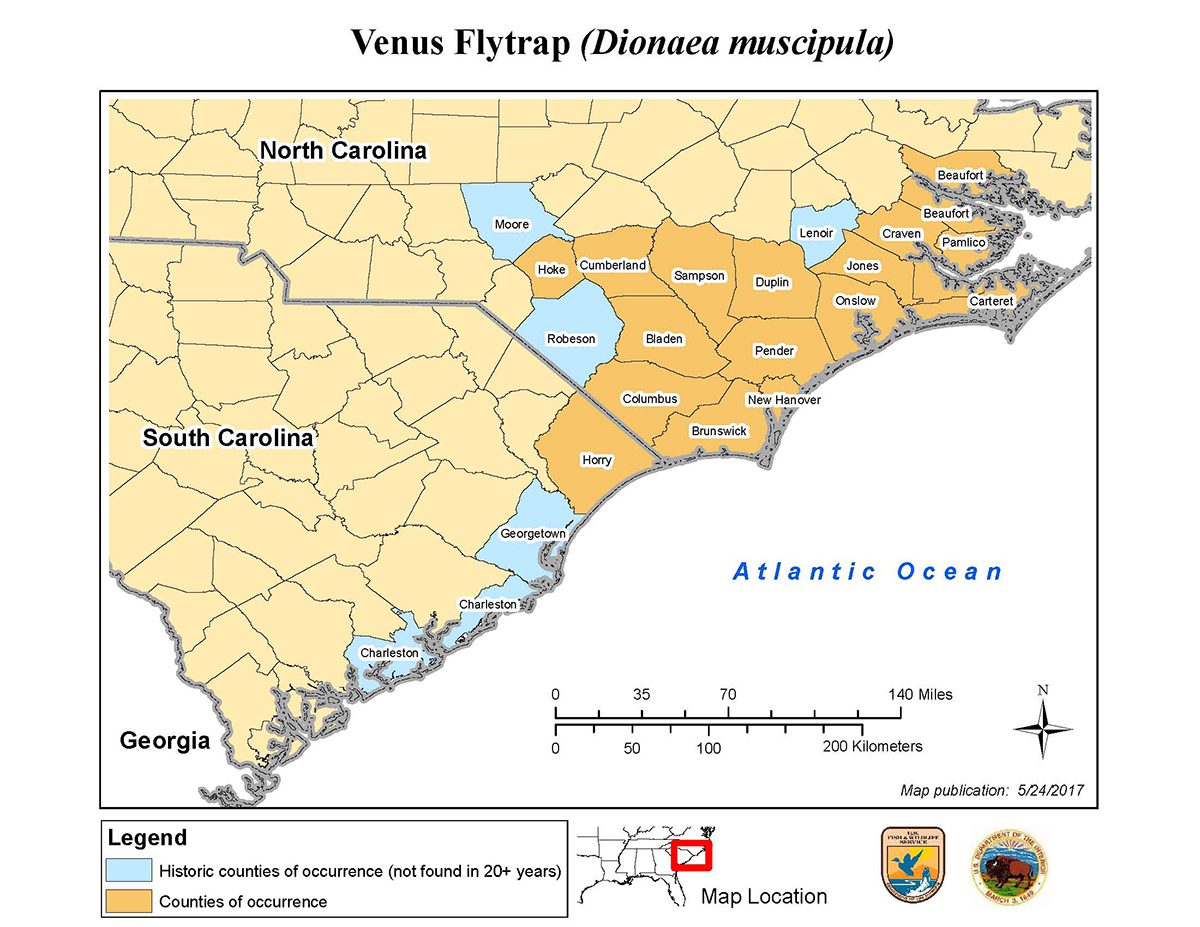

Although they are known around the world, we only find wild Venus flytraps in a few special habitats scattered across the coastal plains of North and South Carolina within about 100 miles of Wilmington. This highly restricted range reflects the flytrap’s needs for open, sunny, nutrient-poor, and wet habitats scattered among seasonally flooded depressions in longleaf pine savannas and along small creeks with shrub thickets in the Sandhills. Flytraps also need recurrent fires. Without them, woody shrubs quickly overtop and shade out these plants.

Development has shrunk the range of the flytrap and extinguished many populations. If you’ve driven to the beach in recent years, you’ve seen golf courses, housing, and commercial areas where flytraps once grew. In addition, poachers who illegally dig up the plants to sell them have depleted many flytrap populations.

The flytrap’s highly restricted range makes it particularly vulnerable. Remarkably, more than 75% of all wild plants occur in just four large populations on Marine Corps Base Camp LeJeune, NC state game lands, and in the Green Swamp (owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy). Small populations on private lands are vulnerable to losing the habitat patches or the fire and water regimes that sustain them.

These threats and concerns led botanists and conservationists to petition the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 2016 to list the Venus flytrap as federally endangered. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) assigned the plant to “Vulnerable” status on its Red List in 2020.

Despite these threats, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has ruled that the Venus flytrap “is not facing an imminent threat of extinction now or in the foreseeable future” (July 25, 2023, decision). They point in particular to eight “highly resilient” populations they rate as stable, protected, and well-managed, which should suffice to sustain this species, eliminating any need for federal regulatory protection.

Supporter Spotlight

We hope the USFWS is right. We fear they acted on incomplete information and with more optimism and confidence than is warranted. They pin hopes for this species on land managers’ abilities to successfully protect and manage a few remnant populations. History is littered with failures to sustain large and apparently stable and well-managed populations of other species that crashed unexpectedly from unforeseen threats.

In making this momentous decision, the USFWS underestimated the risks Venus flytraps face from climate change. The large flytrap populations that the USFWS rates as most resilient and crucial for viability grow at low elevations along the coast. Sea level is now rising faster than predicted even a few months ago, increasing risks from saltwater flooding during storm surges (which are also increasing). Prolonged droughts are also becoming more common, threatening the moist habitats flytraps depend on.

The pace of development has accelerated on the Carolina coastal plain. The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled in its Sackett decision that isolated wetlands beyond navigable waters are no longer protected from development. This halves the area of wetlands formerly protected. Compounding this threat, the North Carolina Farm Act of 2023 (Senate Bill 532) strips North Carolina wetlands of longstanding safeguards and compensatory mitigation. This further frees developers to drain ephemeral wetlands like those that support flytrap populations on private lands. The USFWS’s decision did not anticipate how these actions would threaten flytrap populations.

The smaller flytrap populations on private lands play important roles by connecting large and small populations that enhance viability and slow inbreeding. They also provide the pathways for flytraps to migrate north and inland as climates change.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service decision not to federally protect the Venus flytrap doesn’t mean this unique species is secure. To ensure that wild Venus flytraps remain part of our Carolina natural heritage, consider what you might do:

- Ask landowners with Venus flytraps on their property to request assistance at Venus Flytrap Champions. This organization recognizes and assists landowners and land managers in the Carolinas who want to care for populations of this rare species.

- In North Carolina visit Carolina Beach State Park and The Nature Conservancy’s Green Swamp Preserve and in South Carolina visit Lewis Ocean Bay Preserve to learn about the Venus flytrap.

- Donate funds to support the ongoing habitat protection and restoration efforts (see www.VenusFlytrapChampions.org website).

- Support the North Carolina Plant Conservation Program, which also maintains properties where Venus flytrap grows, via Friends of Plant Conservation.

- Spread concern for the Venus flytrap among your friends, social networks, and the media. Encourage writers or newspaper editors to cover this story in depth.

Extinction is forever. If these populations vanish, we lose a unique branch of life and the world’s most popular plant.

To stimulate discussion and debate, Coastal Review welcomes differing viewpoints on topical coastal issues. See our guidelines for submitting guest columns. Opinions expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of Coastal Review or our publisher, the North Carolina Coastal Federation.