I recently read a fascinating Ph.D. dissertation that was completed at the University of North Carolina Greensboro in 2011. Written by Dr. Susan Thomas, the dissertation is titled “Chain Gangs, Roads, and Reform in North Carolina, 1900-1935.”

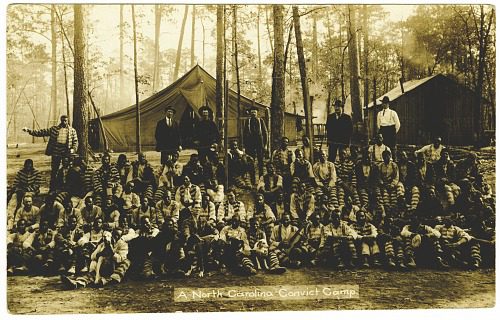

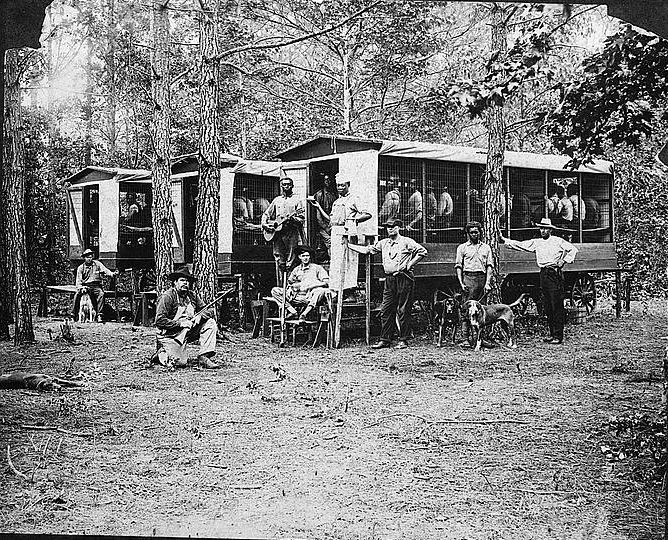

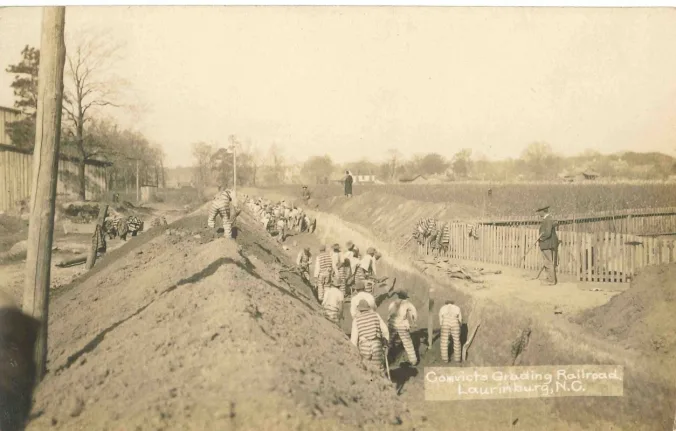

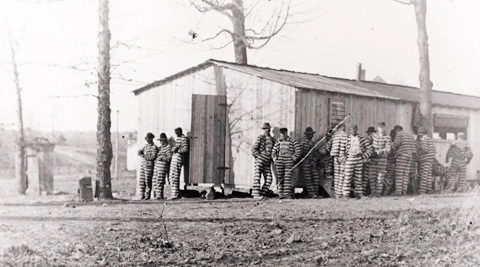

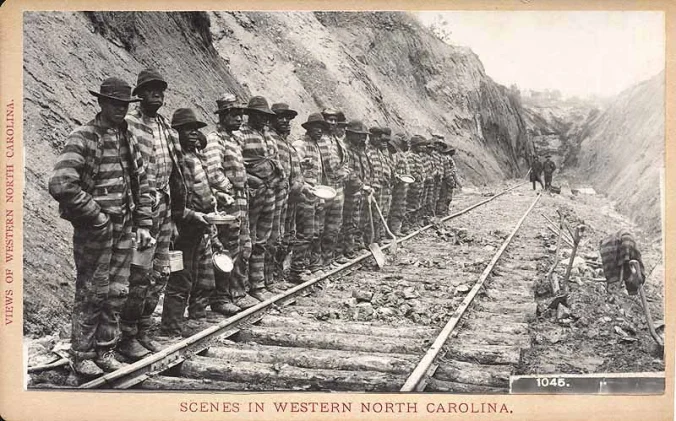

I found it to be a powerful and important work of scholarship. In a series of splendidly researched chapters, Dr. Thomas’ dissertation examines the history of the largely African American chain gangs that built so many of North Carolina’s public roads in the early 20th century.

Supporter Spotlight

Inspired by Dr. Thomas’ work, I requested her permission to share an excerpt of her dissertation here. To my good fortune, she graciously granted me that permission.

The excerpt that I have chosen is about a brief strike that occurred at a convict labor camp in Woodville, a rural community in Perquimans County, N.C., in April 1935.

I chose this passage because I think it gives us a rare glimpse inside a convict labor camp, but also because Dr. Thomas’s dissertation demonstrates how important prisoner protests were to reforming conditions on chain gangs in the early 20th century.

In the case of the Woodville prison camp, she chronicles how the strike played a key role in ending the practice of flogging on chain gangs and in prisons throughout North Carolina.

In our email correspondence, Dr. Thomas noted that the story “highlights the very loosely regulated county structure of the chain gangs. Each county, and sometimes each camp, had been left to do their own thing, leading to much abuse and misuse of power.”

Supporter Spotlight

Dr. Thomas is now a lecturer in American history at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. With her permission, I have made minor edits to help make the passage work better in this format.

* * *

From Susan Thomas, “Chain Gangs, Roads, and Reform in North Carolina, 1900-1935,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina-Greensboro, 2011.

The trouble at the Woodville convict labor camp began in the middle of the afternoon of April 3, [1935] when prisoner James Howell stopped working and, according to later testimony, declared loudly enough for all to hear that “he was not going to work anymore, he didn’t have to work, and Capt. Jesse Johnson [the guard and camp foreman] could not make him.”

Two other men soon joined Howell in refusing to work, stating they were sick. Johnson, the guard, later claimed that Howell “sassed” him, for which he ordered him to stand next to the other men as the convicts continued working the remainder of the day.

When the chain gang returned to camp, Johnson reported the incident to camp Superintendent J. M. Tolar, who ordered Howell and the two sick prisoners to report to the camp doctor. All three prisoners refused to obey Tolar, and instead, filed into their quarters with the other men to await dinner.

Again one of the guards ordered Howell and the others to go to the doctor, but once more they refused, cursing and saying, “They had wanted [a doctor] in the afternoon, and if they couldn’t get him then, they didn’t want him at all.”

When the cook blew the supper whistle, 20 men sharing the same quarters with Howell refused to come out to eat. Tolar did not attempt to force the men out, choosing instead to try to persuade them to cooperate and avoid trouble. Seven men gave in and exited the quarters, but the remaining 13 insisted they were striking and refused to yield.

Unable to resolve the dispute that night, Tolar locked the men away. By the following morning, the number of strikers had more than doubled as they had gained sympathizers among their fellow prisoners. Now a group of 27 men refused to join the other prisoners for breakfast and began to settle in for the duration of the strike …

The Woodville camp contained 180 convicts, making it significantly larger than most others in the state. Only 27 convicts participated in the strike, leaving a sufficient number of men to carry on the work without the prisoners involved in the dispute. The superintendent might have chosen to wait the convicts out, … (but he was) determined to take control of the situation and bring an end to the strike as soon as possible, perhaps to show the remaining convicts the futility of such an action.

Realizing that he was at an impasse with the striking convicts, Tolar sent for a gas revolver and some tear gas cartridges from Sheriff Charles M. Carmine of the nearby Elizabeth City Police Department. While Tolar waited, he tried once more to talk the striking men out of the building, but the prisoners refused to listen.

According to camp officials, the strikers yelled at him and became “defiant and profane in their language.” Some of the convicts told Tolar that “they already had life terms, no one could add more time,” and that he “could not make them come out…no one could make them.”

The prisoners did agree to allow the camp’s road supervisor to enter and talk with some of the men he knew, but he reportedly found them all committed to holding out against Tolar and his armed guards.

As the situation escalated, the tear gas arrived and Tolar decided to end the standoff by driving out the strikers with the gas. To everyone’s surprise, the gas was ineffective — so much so that the striking prisoners ridiculed Tolar for the feeble attempt. There was nothing for Tolar to do but send to Elizabeth City for another tear gas gun and more gas, which Sheriff Carmine delivered personally.

By the time the sheriff arrived, the strikers had reportedly become “positively defiant and riotous.” They had broken legs from the heating stoves and from the beds to use for self-defense and to attack any guard who came close enough. They had also somehow managed to acquire a small cache of bricks, which they used as missiles whenever anyone came too close to the building.

To ensure the effectiveness of the new batch of gas, Tolar ordered his guards to go inside the stockade and close the windows. The guards attempted to obey, but they found that the prisoners were so threatening they could not gain access to the building.

Unable to seal up the stockade, Tolar then declared the area within three to four feet of the windows the “dead zone.” He ordered the guards to shoot anyone seen near the windows trying to get fresh air once gas started filling the building, but to be sure to “shoot low and not at close range.”

Tolar also warned the prisoners to stay clear of the windows or risk being shot. Emboldened by the failure of the tear gas dud and their unity of purpose, the prisoners mocked and chided the guards, telling them they “didn’t have the nerve to shoot.” Tolar then shot eight shells of tear gas into the building and waited for it to take effect.

None of the prisoners inside the stockade laughed this time. The dense fog of gas forced the strikers to enter the dead zone as they sought out the open windows, gasping for air. Seeing the convicts coming to the windows, guards complied with Tolar’s orders, shooting and wounding two convicts who tried to escape the noxious fumes by running out the door. The agitated prisoners managed to drag the wounded men back inside and threatened to attack anyone who attempted to come in and remove them, but they eventually relented and allowed guards to carry them out to the doctor. Twenty-five convicts remained inside the stockade, stubbornly refusing to give up their fight, despite the debilitating effects of the tear gas.

Around 3 o’clock that afternoon, the district prison supervisor, P.E. Mallison, arrived from Rocky Mount with more tear gas…. New to the scene and determined to end the confrontation, Mallison threatened to use the gas to drive the convicts out of the building if they chose to continue their resistance. The convicts knew they could not tolerate another bombardment of tear gas. Defeated, they filed out of the stockade, walking in pairs, hands raised above their heads in surrender.

Mallison assumed control and ordered guards to handcuff the men and detain them for questioning. Twenty-four hours after prisoner James Howell told Capt. Johnson he would not work, the first phase of the ordeal was over.

Reporters for Elizabeth City’s newspapers, The Daily Advance and The Independent, had arrived at the camp just after the shotgun wounding of the two prisoners who had tried to escape the tear gas. They were no doubt aware of the events through the participation of Elizabeth City’s sheriff in providing the two batches of tear gas Tolar used on the prisoners.

Word of the strike spread quickly, and soon [Asst. Superintendent of Prisons] L.G. Whitley … was phoning to speak with Tolar. Prison camp officials and law enforcement officers from surrounding counties, curious to find out what was happening, trickled into the Perquimans site to offer assistance and observe the situation first-hand.

Within hours of the strike’s conclusion, prison supervisor Mallison, the highest-ranking prison official on site, held an informal hearing to investigate the cause of the strike, assess guilt, and determine punishment …

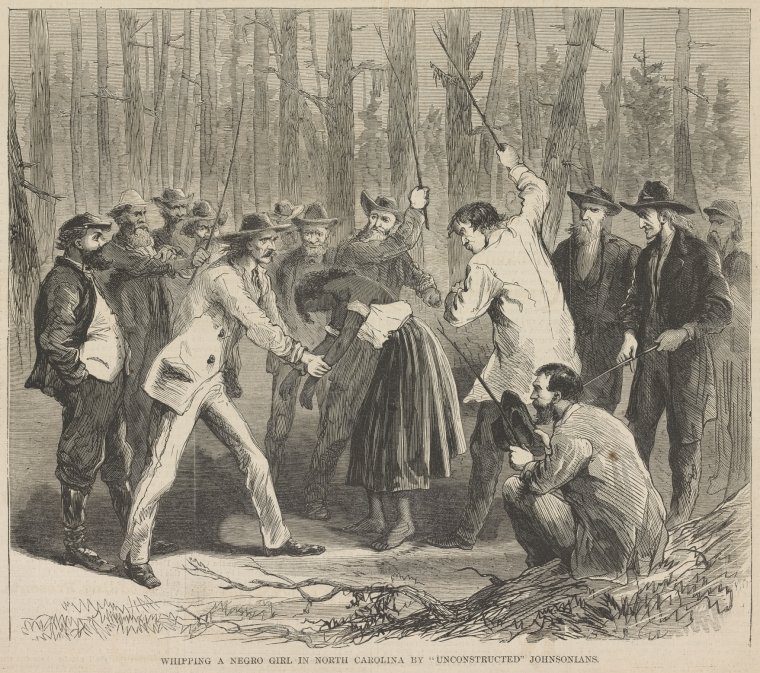

After he finished interviewing the prisoners, Mallison instructed Tolar to “get the leaders and whip them if he thought it necessary to enforce discipline.” Tolar responded by selecting the 13 men he deemed most responsible for the strike, likely those who initially refused to exit their quarters for dinner.

He instructed the guards to remove the offenders to the dining area, where they ordered the convicts to strip to their underwear and lie face down on mattresses placed on the floor for the occasion. Tolar chose Pitt County’s prison camp superintendent to administer the whippings because, as he later told investigators, “He had less biases” than the men who worked in the Woodville camp.

Delegating a supposed outsider to punish the striking men was Tolar’s way of protecting himself from future reproach. Tolar later admitted allowing Johnson, the target of the strike, and another guard from the Woodville camp to participate in the whipping.

Each prisoner received from 10 to 25 lashes with a two-inch leather strap. Although witnesses, including those who had come from other camps, confirmed that the flogging drew blood out of all 13 prisoners, Tolar informed reporters that the whippings were not brutal and, as required by regulations, the camp doctor had been in attendance.

Had there only been the matter of the brief strike, the Woodville episode might have ended there. However, despite Tolar’s caution in selecting men to administer punishment, the floggings became a magnet for criticism and drew a rapid response from across the state.

Tolar’s attempt to deal with his “rebellious prisoners” by flogging sparked a round of equivocation from those in authority over the state’s prison camps. The resulting discourse exposed longstanding fence straddling that had characterized official attempts to regulate or banish flogging on both the county chain gangs and in the state penitentiary.

For the previous two decades, whenever flogging became newsworthy, the judicial system, legislature, county officials, and penal reformers addressed questions such as whether to flog prisoners, and if so, then when and how to administer the punishment and who should be in charge of it.

At several points over the years, the public understood that the legislature and even several governors had banned flogging…. Only after a questionable incident became known, as in the case of the Woodville strike, did it become clear that those who had periodically attempted to eliminate flogging and declared it illegal either had no control or had failed to enforce the purported ban.

With the unification of the penal system into a department within the state government, the debate over acceptable forms of punishment emerged once more.

State Board of Charities and Public Welfare, or SBC, files do not contain records that documented the number of floggings or the offenses that warranted the lash, but media coverage shows that throughout the 1930s prison officials were still using this method to punish prisoners.

In 1931, the same year the state created a unified penal system that included all county convicts, officials in one of Wake County’s prison camps administered a number of floggings that quickly renewed the debate over use of the lash.

The SBC and the governor established a temporary ban on flogging in September 1931 but did not settle on rules until April 1932. The regulations limited methods of punishment to reduction in grade, restricted diet, or solitary confinement. There was no mention of flogging.

As questions arose about the legality of flogging the Woodville prisoners, penal authorities began pointing fingers at one another rather than clarifying state policy.

Meanwhile, the Raleigh press reminded North Carolinians that in both 1923 and 1925, a full ten years earlier, Governor Cameron Morrison had issued an executive order forbidding whipping prisoners in the state penal system. He had acted in the wake of trials concerning mistreatment of prisoners in the county chain gangs….

Confusion surrounded the investigations [that] various state bodies launched into the strike and Tolar’s response to it. Apparently, they concluded, no one was legally accountable for the policy that enabled Tolar to order the floggings.

Before the Perquimans strike, a committee working to revise regulations for the state’s prison camps was poised to recommend the continued use of the lash. After the floggings at Perquimans, the committee reassessed its position.

The new guidelines the group submitted the week following its investigation of the strike and the floggings stipulated that there should be “no further use of corporal punishment without definite formal instructions from Raleigh before the fact.” Any prison employee violating the regulations would be subject to removal.

The penal committee intended for the new regulations to limit severely the use of corporal punishment, while providing for stricter oversight and a clear chain of command.

Some of the men who went on strike in Woodville paid a painful price for their actions, but they also accomplished the outcome for which they had hoped. By the third week of April, barely two weeks after the strike, all camp guards had resigned, including Jesse Johnson, the man the convicts had targeted….

The Elizabeth City Independent placed the story on the front page of the paper and began the article with the statement, “The effects of revolts, strikes, and rebellions are seldom fully realized until sometime after they occur.”

This reporter interpreted the guards’ resignation as a victory for the convicts, and surely for the men in the Woodville camp, this was indeed true. Through their resistance, James Howell and his fellow prisoners participated in framing the political debate over chain gang labor and helped bring the power of the state to bear on the abusive treatment they endured.

You can find the full account of the Woodville convict labor strike as well as the rest of Dr. Thomas’ dissertation, including her footnotes, online here. I want to thank Dr. Thomas again for allowing me to excerpt this part of her dissertation.

* * *

Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.