North Carolina Erosion and Sediment Control Program officials say that because of construction and development, thousands of acres of land are left vulnerable to erosion each year, which can lead to waters polluted with sediment.

The state is working to reach the public and professionals about controlling erosion and preventing sedimentation through its erosion and sediment education program.

Supporter Spotlight

A part of the Erosion and Sediment Control program with the mission “to allow development within our state while preventing pollution by sedimentation,” the program is under the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Energy, Mineral and Land Resources.

Sediment Education Engineer Rebecca Coppa explained to Coastal Review that erosion of exposed terrain — often land made vulnerable through human activity — strips away nutrient-rich topsoil, degrading the soil and making it less productive, leading to sedimentation, or when the eroded soil is moved and deposited by water or wind.

“It takes about 500 years to naturally replace one inch of topsoil,” Coppa said.

“Sedimentation can increase the risk of flooding by reducing the storage volume of water bodies and by clogging storm water drains,” Coppa continued, adding that sedimentation can clog fish gills, smother bottom-dwelling fish and their eggs, and cause turbidity, which is when the sediment makes water look cloudy, opaque or muddy.

“Turbid water negatively impacts recreational use of water, restricts the amount of sunlight reaching aquatic plants, and increases the cost of drinking water treatment since you need to filter all of that out,” Coppa said. “Harmful substances such as pesticides and fertilizers can also hitch a ride on the sediment particles that are washed off the landscape and into waterways, and can contribute to things like algal blooms, which can also harm aquatic life.”

Supporter Spotlight

One way to control erosion and prevent off-site sedimentation is to use best management practices, or BMPs. BMPs include replanting vegetation in disturbed areas, controlling rates of runoff and putting in place basins, rock dams and sediment traps.

Coppa said educating the public about erosion and BMPs is the mission of the erosion and sediment control’s education program.

“There are many avenues that we have to inform, educate and help the general public, residents, local and county governments or professionals,” Coppa said. These include keeping the Erosion and Sediment Education website current, having a Frequently Asked Questions page, providing forms, guidance documents and information packets to teachers and professionals, offering workshops for professionals, and attending events.

There are two workshops. The local program workshop is held annually by the department’s Land Quality Section to educate and train staff for their erosion and sediment control programs. For information on this workshop visit the Local Government Programs page. The North Carolina Erosion and Sediment Control Workshop is to educate design professionals, contractors and developers with new erosion and sediment control requirements and practices, and fulfills professional development hours. Registration and the agenda will be posted on the workshop’s event page as it becomes available.

Outreach to younger learners include special activities like the curriculum supplements “Erosion Patrol” for third and fourth graders, and “Where Is All Our Soil Going” for middle schoolers.

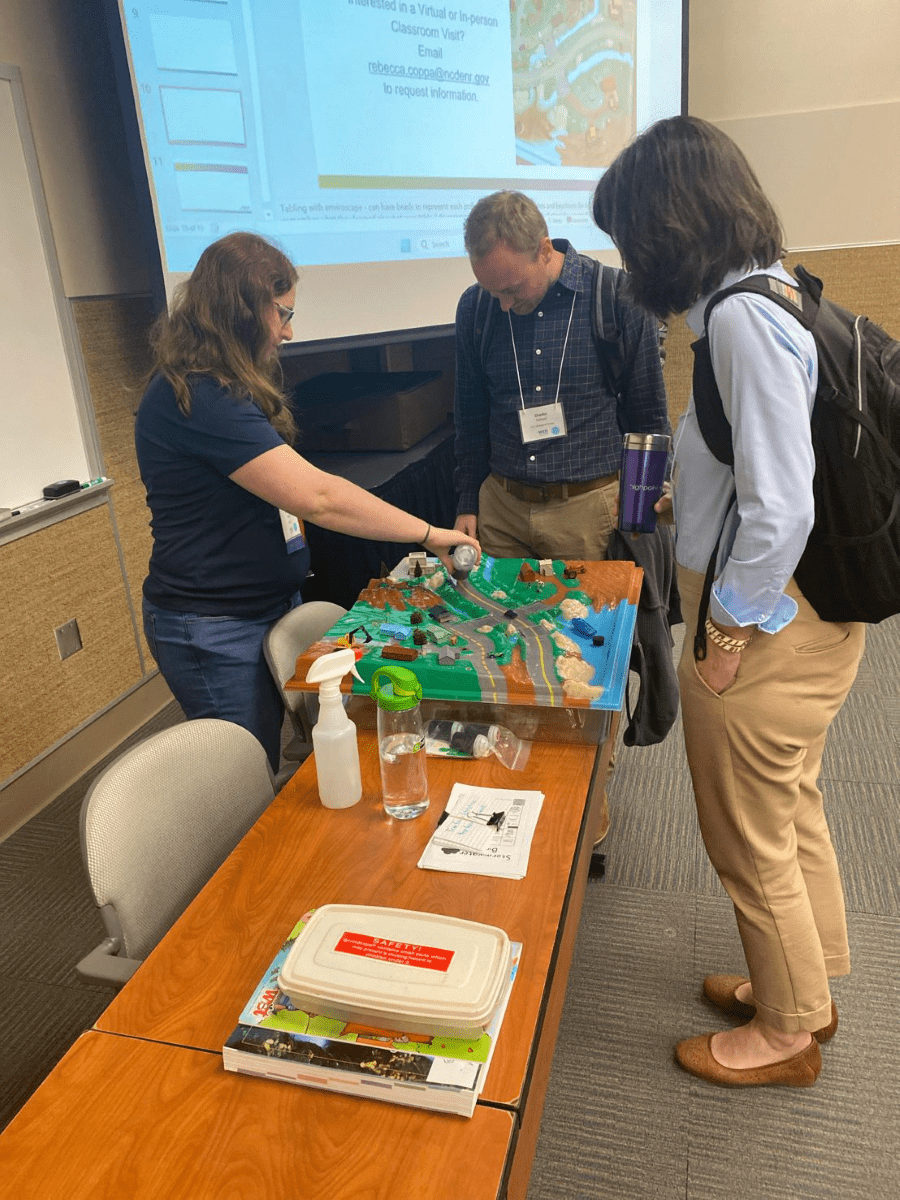

One tool Coppa and other educators use is called Enviroscape. These 3-D educational models demonstrate how watersheds can become polluted and are sold through a private company.

Coppa said that she has been using Enviroscape since she began working with the state five years ago, and other educators have relied on it as well, including DEMLR Chief of Program Operations Toby Vinson.

Vinson said Enviroscape is a valuable tool he’s been using since 1994 to present the impacts of erosion and sedimentation and other pollutants to the environment, community and property to K-12 and college students, at workshops instructing contractors, developers and engineers and at community festivals.

Evangelyn Lowery-Jacobs, assistant regional engineer in DEMLR’s Fayetteville Regional Office, added that Enviroscape helps to translate technical concepts into real life, relatable terms. She mostly used the teaching aid with elementary and middle school students.

“I did have one opportunity to visit a class to conduct a demonstration for developmentally challenged adults. Enviroscape allowed the students to observe and interact because of their ability to identify with things they had been exposed to in their personal lives,” she said. “The eagerness to answer questions was obvious and the model encouraged dialogue among everyone in the group. This encounter gave me a new perspective on the value of this model and its effectiveness for people of all ages and backgrounds.”

Coppa said interactive, hands-on educational activities help communicate the message because being able to see, touch and play with something “helps us learn about it so much better than just reading about it or listening to it in a lecture.”

During her presentation at the North Carolina Water Resources Research Institute’s annual conference earlier this year in Raleigh, Coppa shared how educators can enhance their Enviroscape activities with basic materials, like cocoa powder can simulate sediment.

She expanded in a recent email interview that the Enviroscape brand provides ideas for materials that can be found at low costs at many stores, which allows for flexibility.

“Personally, I like to use various sprinkles (jimmies if you’re from the north) to demonstrate different pollutants. Rainbow sprinkles for trash/plastic pollutants; chocolate sprinkles for feces (such as cow poop or dog poop); and sugar crystal sprinkles of various colors to represent fertilizers, pesticides and point source chemicals from factories,” she said. “Obviously, the chocolate sprinkles representing poop is the one that gets the best reaction from the students. But we also can’t forget what we use to represent the number one pollutant by volume to NC’s waterways: coco powder to represent sediment.”

Other ways she enhances her lessons is by pairing Enviroscape with an erosion or stormwater walk, and incorporating activities through Project WET, or Water Education Today, a water education foundation.

“I’ve paired the Enviroscape with a sediment jar activity and/or soil texture by feel analysis and discussed why soil texture is important in terms of erosion. Plus, then students get to play with both soil as well as the water on the Enviroscape model; all of the learning through play,” she said.

Each of DEMLR’s seven regional offices throughout the state have an Enviroscape Watershed Model and while she’s the only staff primarily dedicated to education and outreach, regional office staff can visit as their schedules allow.

“The expansion of virtual meeting software during the past few years has also increased our capacity to how far we can ‘travel’ if you’re willing for us to come to your classroom virtually. Virtual visits without travel time are often easier to fit into our schedule and we can send you activity instructions ahead of time so your students can follow along with what we are demonstrating on screen,” Coppa said.

She added to contact her with any education outreach requests and she will help coordinate visits with regional office staff if she’s unavailable to make it herself.

“Part of our role as nonformal educators is to be there to support the formal educators of North Carolina. So, if they have questions beyond what is already available on our website, we are a short email away and are happy to brainstorm with you about how we can work to fill in the gaps within our respective education programs,” Coppa said.

A graduate of Worcester Polytechnic Institute with a bachelor’s in environmental engineering, Coppa has been educating about sediment control for almost five years.

“That four-year degree combined with my volunteer work with kids throughout my high school and college career and extracurricular work planning events made me a good fit for this job,” she explained.

“The environment has always been something I’ve been passionate about, and my passion for environmental education, getting learners of all ages outdoors, and letting them learn through play, has only grown these past few years as I’ve been learning so much myself as I am pursuing my North Carolina Environmental Education Certificate,” Coppa said. “And as that passion has grown, I’ve made a conscious effort to bring the Enviroscape, soil or water or other things that the students can touch and play with if I can’t get the student’s outside. Because the more the students interact with the lesson and materials, the more I see them lighting up, becoming interested, and hopefully remembering what they learned for years to come.”