If a Raleigh-area volunteer effort to help fill the gaps in wetlands data continues its current path, the monitoring program could expand across the state.

The Carolina Wetlands Association, North Carolina State University and RTI International have been developing the pilot wetlands monitoring program over the past few years.

Supporter Spotlight

Michael R. Burchell, professor and extension specialist with N.C. State’s Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, recently explained to Coastal Review that the project that’s funded through the Environmental Protection Agency’s wetlands program development grant was designed to see how viable it is for volunteers to collect wetland data.

The pilot program was awarded funding four years ago, right before COVID-19 restrictions were put into place. During the last year, Burchell said the team has been able to move forward with the project.

When Burchell presented the project on behalf of the team during the N.C. Water Resources Research Institute’s annual conference at N.C. State University’s McKimmon Center in Raleigh earlier this year, he explained that a benefit of a sustained ambient monitoring program is understanding the health and promoting protection of wetlands are critical to preserving our ecosystems.

“Monitoring and having some sort of ambient monitoring program could be really important to track wetland loss impairment. Wetlands can serve almost as a canary in the coal mine. If you know what the quality of the water coming into a wetland is, you get some ideas about what’s going on your watershed, hopefully, before it starts impacting your stream and other surface water quality,” Burchell said during the conference. But these programs are hard to fund, and a volunteer science program may be the answer because the project could be sustained in the long term with limited financial support.

Burchell told Coastal Review that the project came about after years of funding challenges made it hard for the state to maintain wetland monitoring.

Supporter Spotlight

Partners for the project, which includes Carolina Wetlands Association Executive Director Rick Savage, began pursuing the idea. In the process, they found that there’s not many volunteer-based wetlands monitoring programs.

“It’s not the norm at all,” Savage told Coastal Review, normally volunteers monitor streams or rivers, not wetlands. Burchell added that this is because wetlands are more complicated to monitor.

Burchell said the partnership with the Carolina Wetlands Association allowed for the volunteer program to build on the association’s established goal, and give the program presence on the association’s existing website. The program page includes the training for volunteers that the team developed, which covers basic safety, field work, data-collection software, and other resources.

Work also went into recruiting volunteers through the association’s online presence and network. Savage said they have about 40 volunteers now, in some capacity, ranging in age and experience.

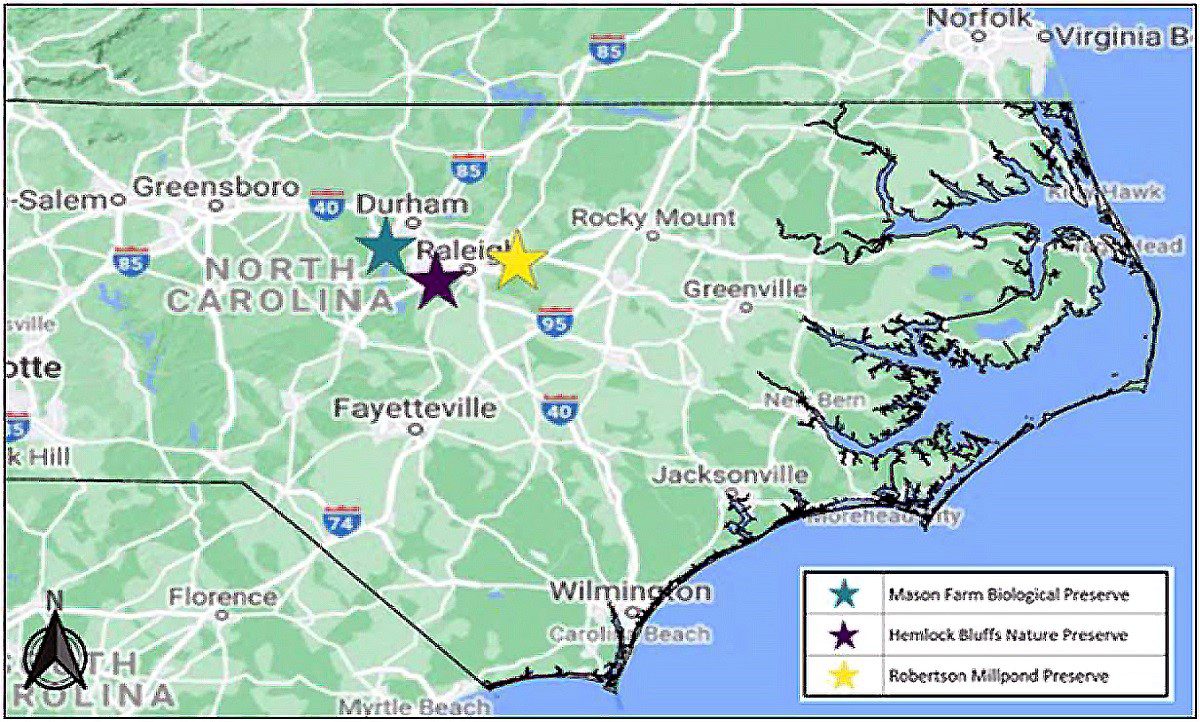

Between February 2022 and March of this year, there have been five monitoring events. The groups of up to 10 volunteers have collected data on hydrology, water chemistry, soils, vegetation and wildlife at Mason Farm Biological Reserve in Chapel Hill, Hemlock Bluffs Nature Preserve in Cary, and Robertson Millpond Preserve in Wendell.

“Right now, the pilot appears successful. We’ve only done this one year, but it certainly seems to be gaining momentum,” Burchell said at the conference.

Burchell explained to Coastal Review that they tell the volunteers that this kind of project hasn’t really been done before and they are always looking for feedback on what works and what doesn’t, or if things should be done differently.

“Ultimately we want to be reporting about what went right, what didn’t go right, what we did to fix it, and where we think that it could go in the future,” Burchell said.

Savage added that they’ve “been pretty happy with the way it’s been going. We’ve learned a lot and we’ve made adjustments accordingly, and we still are to some extent.”

Burchell said that they chose the Raleigh-area wetlands because of logistics. These sites are close to the university and the Carolina Wetlands Association headquarters, and are diverse, high-quality wetlands that are under some management as part of a conservation site.

“We want the data to actually be used by other wetland managers — whether it’s people in DEQ or the Coastal Federation — looking at doing a conservation easement. Or if they want to know what the hydrology of a similar wetland might be, they could use this data,” Burchell said. Or “perhaps people who are in the restoration industry are curious about what they would expect the water quality to be from one of these areas.”

Currently, they’re still in the data-collection stage, and the data sharing part of the project is under development.

Savage said the next important phase that’s probably going to get the most emphasis is getting the data portal set up, most likely on the association’s website. RTI International is developing the data portal as its part of the partnership.

The partners plan on applying to the EPA soon for funds to continue the project “but expansion has got to be the key word there,” Savage said.

In addition to the training and materials that have been and will need to be created, Savage said as the project expands, the team is looking for organizations to help with the volunteers.

The Carolina Wetlands Association will be the lead for the program and would provide training to organizations and volunteers, Savage said, but “ultimately, it’ll be the organization that manages the volunteers.”

This means making sure the volunteers collect data from the sites at the right times of year, complete certain tasks and collect the necessary data.

“I think that’s going to be a really important aspect,” to expand the program to reach the long-term goal of a self-sustaining wetlands monitoring program across North and South Carolina, Savage said. It would be overwhelming to manage all the potential volunteers. “We’re going to need organizations to work with us to manage the volunteers.”

Savage added that the organizations would be encouraged to engage their volunteers year-round.

“That’s probably as important as anything,” he said, explaining that outreach may be easier for these existing organizations. This the project team’s first time with this kind of work, and while “I think we’re doing OK” at keeping the volunteers excited and engaged, “we can always learn.”

Savage said they’ve had a couple of organizations already contact them to get involved, but the program is not quite set up for that step, yet.

‘I think this is exciting. It means, I think, that we’re doing something right and we’re getting other organizations interested,” Savage said. The goal is to reach out to these organizations and include them in this network as soon as possible, but most likely during the next funding cycle. “I’m really pretty excited to see how we get expanded out and work with these organizations.”

A hope is that with the next phase, there are volunteers from under-represented populations and groups from communities with wetlands, Burchell added.