ROANOKE ISLAND — Archaeologists have unearthed artifacts that appear to confirm the site of the Algonquian village on Roanoke Island, where Native Americans shared their dinner with the first English explorers.

“This is firm evidence that this locality was Roanoac, the village of first contact,” Eric Klingelhofer, vice president for research of the nonprofit First Colony Foundation, told a small group of reporters Friday during a briefing at the excavation site. “We’ve known about the village because that’s the place where English explorers sent by Raleigh first came.”

Supporter Spotlight

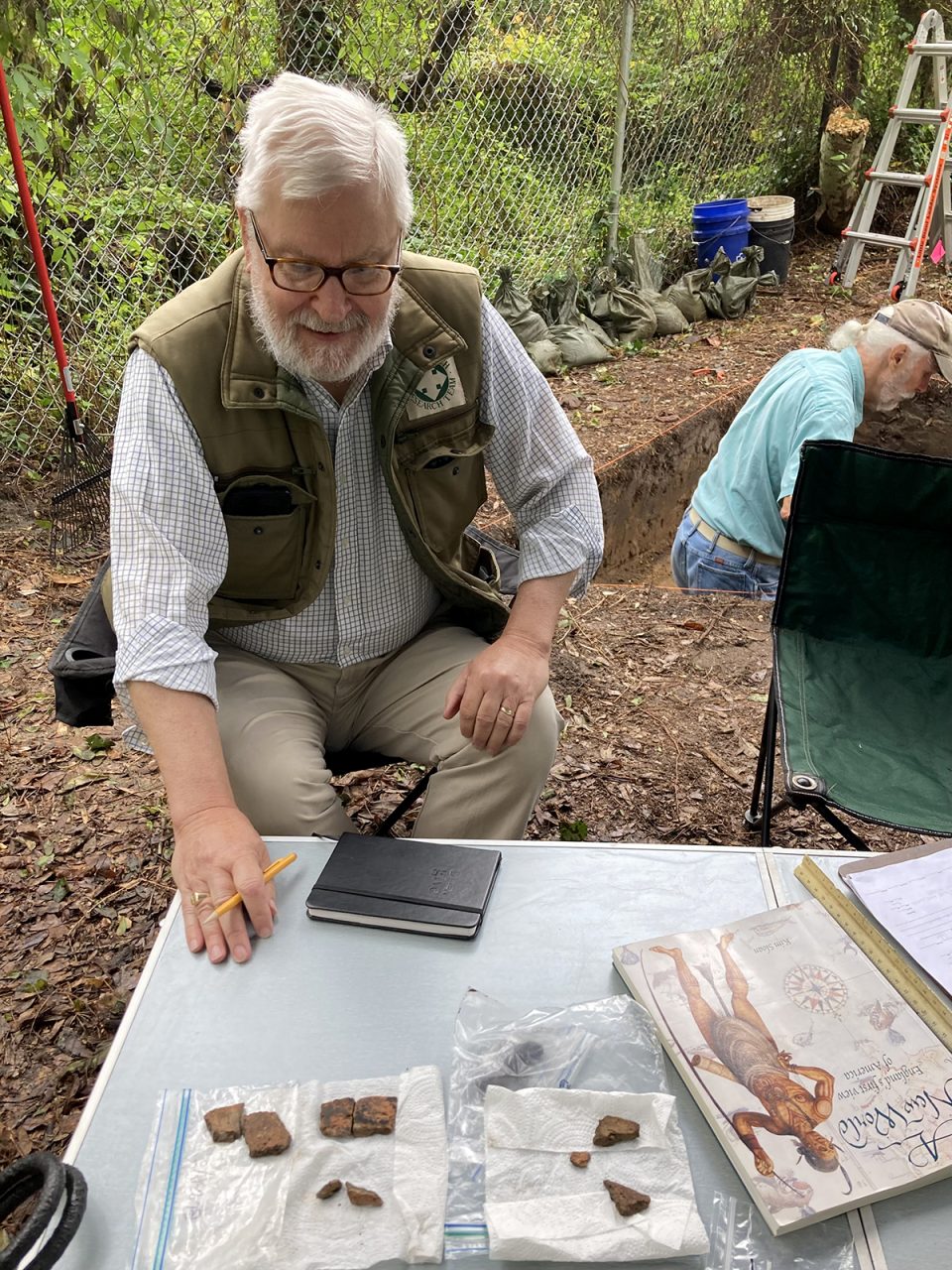

Pointing to broken pieces of pottery laid out on a makeshift table — a sample of the finds — the veteran archaeologist explained that the sherds came from Algonquian Colington ware and burnished ware pottery, both found during a recent excavation of the 16th century strata.

“Now that’s not the full story,” Klingelhofer added with a sly grin as he reached for small plastic bag. ‘’We found something else.”

He then gently pulled out a thread of copper that was bent into a ring shape, and was buried about 3 feet down in the top layer. Copper was much sought-after by Natives in the Southeast, but it was rare in the region and was nearly all acquired through trade.

“I was extremely pleased because I knew what it meant,” said Klingelhofer, referring to English contact. As he spoke, the waters of Roanoke Sound could be heard lapping at the shoreline behind the dig site, hidden by lush trees and bushes at the privately owned Elizabethan Gardens adjacent to Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

Copper was a known currency for the first generation of American colonization, Klingelhofer said, adding that the copper strand most likely was a trade item that may have been worn by a Native as a ring.

Supporter Spotlight

“There’s no other reason it would be here,” he said. “It must have come from the colonists.”

The Foundation team has asked conservators at Jamestown to analyze the copper, he said.

English explorers Phillip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe visited Roanoac in 1584 as part of a reconnaissance mission planned by Sir Walter Raleigh. The men were welcomed by the Algonquians, who invited them to dine and exchanged gifts with them. The Englishmen later described Roanoac as having nine cedar houses fortified in a round of “sharp trees.”

The following year, Ralph Lane, who was part of a larger Raleigh expedition, had been sent to Roanoke Island with about 100 soldiers to establish a fort and a settlement. Lane abandoned the island in 1586 because of hostilities — much apparently provoked by him — between the Native population and the English. Nonetheless, about 117 men, women and children from England arrived on Roanoke Island in 1587 to establish a permanent settlement. Known today as the “Lost Colony,” it disappeared without a trace and is often called the oldest mystery in American history.

Founded in 2003 by Klingelhofer and other professional archaeologists, the First Colony Foundation has conducted numerous archaeological explorations in and around Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on the north end of Roanoke Island, which is where the Lost Colony settlement is likely to have been built, as well as sites in Bertie County at the headwaters of the Albemarle Sound where, artifacts show, a small number of colonists likely had fled.

Findings over the years from Foundation digs have ranged from remnants of early wells, sherds from olive jars and pottery, a Cashie-type Indian pot, tobacco pipes, French ceramic flasks, glass trade beads, and an entire necklace of cut diamond-shaped copper sheets that the team believes may have been presented to a Roanoac noble. Advancements with remote-sensing technology have enabled First Colony researchers to eliminate some sites while homing in on other areas.

Klingelhofer and Foundation Co-Vice President Nick Luccketti had been part of late archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume’s Virginia Company Foundation team in the 1990s that determined that an area presumed to be associated with the reconstructed “Fort Raleigh” earthworks was instead the 1585-1586 workshop used by scientist Thomas Harriot and the metallurgist Joachim Gans — a notable discovery.

Further tests revealed evidence nearby of charcoal making and a brick kiln and led to other digs to the north and west that found 16th century artifacts. The work with Hume directly influenced establishing the First Colony group to create a partnership agreement with the National Park Service so that Elizabethan-era explorations could continue.

Although the Foundation, which includes academics and historians with expertise in precolonial and early colonial American activity and Native American culture, would welcome finding evidence of the Lost Colony, its focus has always been the broader story of the 1584-1590 Roanoke Voyages, which served as the playbook for English colonization and ultimately, for what became America.

Klingelhofer said that the team is up against time, as increased shoreline erosion consumes places to explore, and storms reconfigure potential historic areas.

Going back as far as the Great Chesapeake Hurricane in 1769, sand had buried the 16th century site where archaeologists have recently dug. So far, Klingelhofer said, about 100 feet of shoreline has been lost on the north end of Roanoke Island, and water in the Albemarle Sound is about 3 feet higher than it was in the 1580s.

For the time being, he said, work on Roanoke Island is done. Meanwhile, he said he was looking forward to publication in November of a book detailing archaeology and historic research done by the Foundation and its predecessors, “Excavating the Lost Colony Mystery, The Map, the Search, the Discovery,” which is edited by Klingelhofer.

But the team plans to resume explorations soon at other sites in and around Fort Raleigh and Bertie County. They will also expand beyond the Native American village excavation to see how far it goes, now that the location has been nailed down to their satisfaction.

“So it’s been a good little dig,” Klingelhofer said. “We are very happy to bring our search for Roanoac to a conclusion.”