When 85 men, women and children lost their lives Jan. 31, 1878, as the Metropolis broke into pieces in the Currituck Banks surf, it was the final chapter in the story of a ship that should not have put to sea and, according to new research, may still rest on a Currituck beach.

In his recently completed master’s thesis, “From USS Stars and Stripes to Metropolis (1861-present): Modeling the Life, Loss, and Archaeological Site Formation of a Currituck Beach Shipwreck,” East Carolina University researcher Matthew Pawelski details the history of a once-proud Civil War naval vessel from its launch to its final voyage. Taking that information and using historical records, computer-aided design and 3D imaging, he found strong suggestive evidence that wreckage from the Metropolis remains on Corolla Beach.

Supporter Spotlight

The sinking of the Metropolis with its horrific loss of life came just two months after the USS Huron broke apart and sank 200 yards from the Nags Head Lifesaving Station that was closed for the season. Ninety-eight men lost their lives at that time. The combination of the two tragedies brought national attention to the shortcomings of the Lifesaving Service and prompted Congress to fully fund the service that was the predecessor to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Stars and Stripes

The Metropolis began life as the Stars and Stripes. Launched in spring 1861, the ship was described in Pawelski’s paper as a “smart looking three masted steamer.”

With the surrender of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces on April 13, 1861, the U.S. needed to quickly expand its naval fleet, and the Stars and Stripes, at 150 feet long with a beam of 34 feet, was exactly what the U.S. Navy needed.

Over the next four years, the ship was engaged in numerous battles, including significant action in North Carolina waters.

“All told, USS Stars and Stripes captured or destroyed six blockade runners, destroyed numerous supply sources and land-based units, and engaged in two battles of note, those of Roanoke Island and New Bern,” Pawelski writes.

Supporter Spotlight

Time as a merchant ship

After the war ended, the Stars and Stripes was decommissioned and sold as surplus, spending the next six years as a merchant ship until it was purchased by the Lunt Brothers, an East Coast shipping company.

After 10 years of hard use, the ship badly needed work, but rather than repair their new purchase, Lunt Brothers surrendered the ship’s registration, claiming it could not be salvaged. The company then took the unsalvageable vessel to Newbury, Massachusetts, shipbuilder Eben Manson, owner of Manson Shipbuilding.

Manson cut the ship in two and, “added 56 feet amidships, bringing the vessel to around 198 feet in length …(and) another deck was added,” Pawelski writes. The ship’s rated tonnage increased from 484 to 878.

When launched in August 1871, the ship was renamed the Metropolis, and although rebuilt, questions about its seaworthiness persisted.

It took Manson less than eight weeks to complete the work to lengthen the Metropolis to 196 feet. Pawelski told Coastal Review that was not enough time to properly rebuild the Stars and Stripes.

“In order to make that ship go from (approximately) a 500-ton to 1,000-ton (vessel), you’d have to take it all the way down to the studs, and you don’t have time for that in five to eight weeks,” he said.

The rebuilt ship needed extensive repairs on two separate occasions, the second time in December 1877 after the Metropolis ran aground off Hampton, Virginia.

Final voyage

Nonetheless, the Metropolis was in Philadelphia Jan. 22, 1878, loading 700 tons of cargo, including 500 tons of steel rail for a railroad project in Brazil. There were also 248 passengers and crew on board, most en route to Brazil to work on the railroad project.

When departing Philadelphia the next day, seas were calm, but as the morning wore on Jan. 24, 1878, the ocean became turbulent. That evening, as the ship passed Norfolk, seas continued to rise, and 500 tons of steel rail that was improperly stored began to shift in the hold.

Water was discovered in the hold, and the crew determined that the leak was coming from a damaged sternpost. Capt. J.H. Ankers ordered coal jettisoned to lighten the load. After 50 tons of coal was thrown overboard, pumps began to gain the upper hand. But the steel rails were still shifting below deck and the ship’s seams were splitting.

The incoming water overwhelmed the pumps, and they stopped working. Passengers and crew formed bucket brigades.

Little progress could be made before a large wave hit the vessel around 5 a.m. Jan. 31.

“This wave tore off the smokestack, the vessel’s lifeboats, parts of the saloon deck, steam whistle, and after-mainsail. In addition, the wave also put out the fires in the boilers, completely disabling the vessel,” Pawelski writes.

Ankers, the captain, knew the Metropolis was lost. Hoping to save lives and possibly the cargo, he steered the ship toward land, grounding on the outer bar of Currituck Beach, 300 yards from shore at 7 a.m. Soon after the grounding, a large wave struck the ship and carried it to the inner bar, about 100 yards from shore, about 3 miles south of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse and 4 miles south of Lifesaving Station No. 4.

When told by locals that the Metropolis was on the sandbar, the Lifesaving Service crew immediately headed out. Hauling heavy rescue equipment across a sometimes overwashed beach and toiling into the teeth of a storm, the crew did not arrive on the scene until noon, even with the help of a resident, John Dunton, who loaned them his pony.

The Lifesaving Service’s standard practice in rescuing stranded crews and passengers was to use a mortar to fire a round shot with a heavy line attached to it. The line would then be secured to the ship and affixed on land so that a breeches buoy could be used to bring people to safety.

The first shot fired from the shore went long, but according to Capt. JH Merryman’s report on the incident to the Secretary of the Treasury, first shots were rarely accurate.

“However, familiar or skillful the station men may be in the use of the mortar the failure of the first shot is not unusual as the distance to be reached and the force of the wind are difficult to estimate,” he wrote.

The second shot was on target, but it, too, failed. According to Merryman and Lifesaving personnel, the line was not attached properly to the ship, and as the Metropolis pitched and rolled in the surf, the line snapped.

One of the passengers rescued that day later gave a conflicting account that appeared in newspapers at the time, claiming the problem was the Lifesaving Service crew.

“Owing to the stupidity of the crew on shore, the line was cut off against the jib stay,” according to a report in the Feb. 8, 1878, edition of the Wilmington Post.

Keeper Capt. John Chappell had only brought two charges for the breeches canon, and firing the canon with nonstandard gunpowder borrowed from Currituck residents failed to achieve an accurate shot.

Merryman was especially critical of Chappell, writing that it was an “… inexcusable neglect of the keeper in having but two charges of powder in his flask.”

However, he also noted that Chappell and the personnel of Station 4 risked their lives to rescue people who were desperately trying to swim ashore in the surf.

Still, his most damning criticism was directed at the Metropolis itself, pointing out even the most rudimentary warning system was unavailable.

“If the Metropolis had carried as I am informed she did not, a small gun … for making sound signals of distress … as she neared the land, its reports would have been heard at the light house and also at the station … and there would have been time for the life saving crew to have reached the wreck before the hour they were notified by Mr Brock,” he wrote. Brock was the resident who informed the crew of the wreck.

Merryman also called into question whether the Metropolis was seaworthy.

“I submit herewith two pieces of decayed wood from different parts of the vessel’s frame,” he wrote.

Even though testimony raised doubts about the work Manson had done in 1871 and the general state of the vessel, Pawelski notes, “The only person who took any fall was Keeper Chappell,” who lost his job.

Identification

The Currituck Banks shoreline is part of the Graveyard of the Atlantic, and the skeletal remains of ships are part of the beach, as the sand, wind and tide alternately reveal and then cover the flotsam – remains of ships that floundered offshore.

In winter 2022, Pawelski and a team from the ECU Maritime graduate studies program, including Director of Maritime Studies Dr. Nathan Richards, examined a half-mile stretch of beach, evaluating known archeological sites and identifying a new item of interest. The general onshore location of the 1878 rescue attempt is believed to be about 3 1/2 miles south of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse.

In the past, the archeological sites along that stretch of beach from Albacore Street south for about 2,500 feet have been noted and marked, but rarely have meticulous examinations of them been done. Access to the sites is weather-dependent. The ECU team was on the beach soon after a nor’easter had exposed some of the shipwreck material not regularly seen.

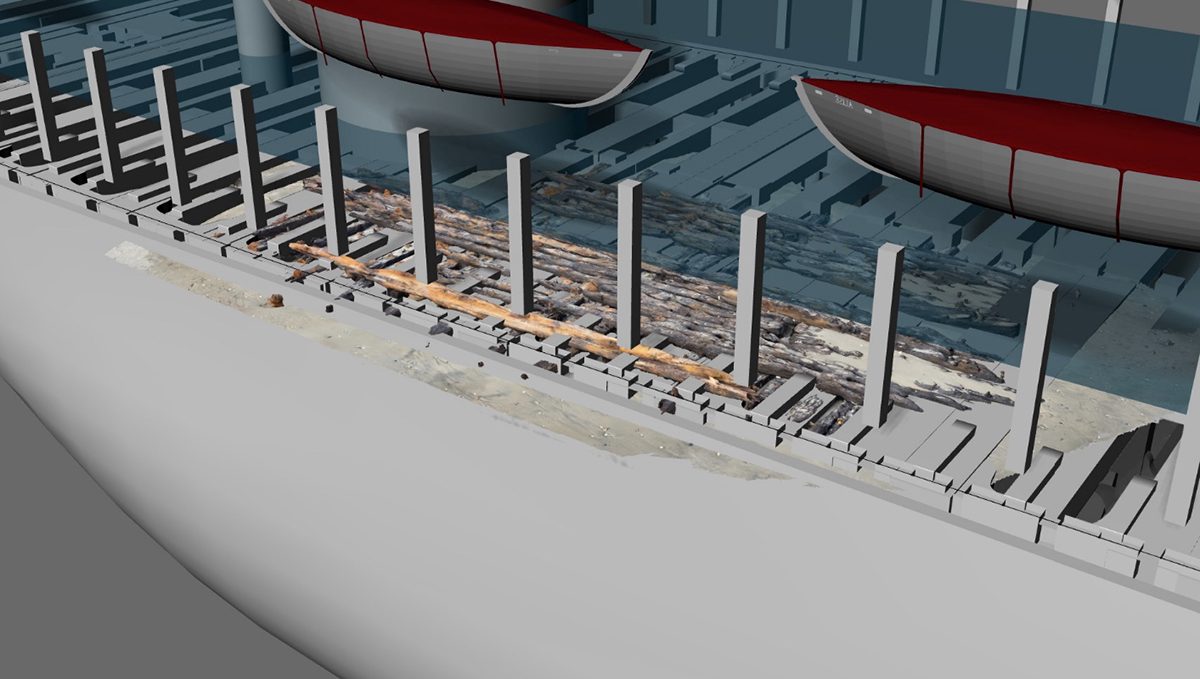

Pawelski, using computer and imaging technology, made detailed on-site measurements, photos, a half model of the Stars and Stripes at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut, and historic paintings of the Metropolis, was able to create a 3D model of the ship’s interior framing and exterior. His work strongly suggests that some of the material on Currituck Beach came from the doomed ship.

The ECU team identified 15 potential sites for additional investigation in the half-mile of beach where they were working. Some were buried sites that instruments had detected, and others clearly could not have been associated with the Metropolis. There were three sites, though, that they found warranted additional examination.

On the north end of the field, the O’Keefe site, CKB (Currituck Beach) 0015, is well known as home to the frame of a ship that has at times been cited as the remains of the Metropolis. Pawelski found the size of the wreck to be close to that of the Metropolis’ known measurements, but the framing at the site is too small and the wood does not match insurance records for the vessel.

The other two sites, one previously unidentified and the Ray Midgett CKB0023 site, revealed more striking similarities to the structure of the Metropolis.

“The unidentified CKB site is potentially part of the bow construction of a ship. Measurements of the site’s timbers made it a prime candidate to be related to Metropolis,” Pawelski found.

The Ray Midgett site, CKB0023, features a large piece of material believed to be decking. This site, when overlaid with a 3D rendering of the Metropolis, appears to match far more precisely than the O’Keefe site.

Pawelski was guarded in his conclusion.

“With the model evidence in mind, it is likely that CKB0023 is a section of Metropolis. However, given the inability to account for the actual deck structure and density of deck beams on Metropolis … along with the presence of so many wrecks along its coast, it is impossible to conclusively say that CKB0023 is a part of Metropolis without specific period correct artifacts or something with the vessel’s name on it,” he wrote.