This report includes outdated racial terms that may bother some readers.

Salmon Creek is a slow-moving, scenic tributary of the Chowan River in Bertie County. At the mouth of the creek on the south bank there is a golf course. On the north side, the Salmon Creek State Natural Area and adjacent Bertie County land that the county is using to develop its Tall Glass of Water park create 1,400 acres of protected forest and wetlands.

Supporter Spotlight

The peaceful setting gives little evidence of its rich history, a history that includes Native American villages at the site and extends to the earliest days of European explorers.

It is here at the mouth of Salmon Creek that the nonprofit First Colony Foundation places the Lost Colony Site X that was discovered in 2012 hidden on a 1585 John White map.

As the stream meanders to the heart of Bertie County, it seems far removed from the time when it was once one of the most prolific shad and herring fisheries in the nation – a fishery that David Cecelski describes in his 2001 book, “The Waterman’s Song Slavery and Freedom in Maritime South,” as “… by far the most prominent commercial fishery in the South prior to the Civil War. It was also the only major commercial fishery in North America that relied exclusively on slave and free black labor.”

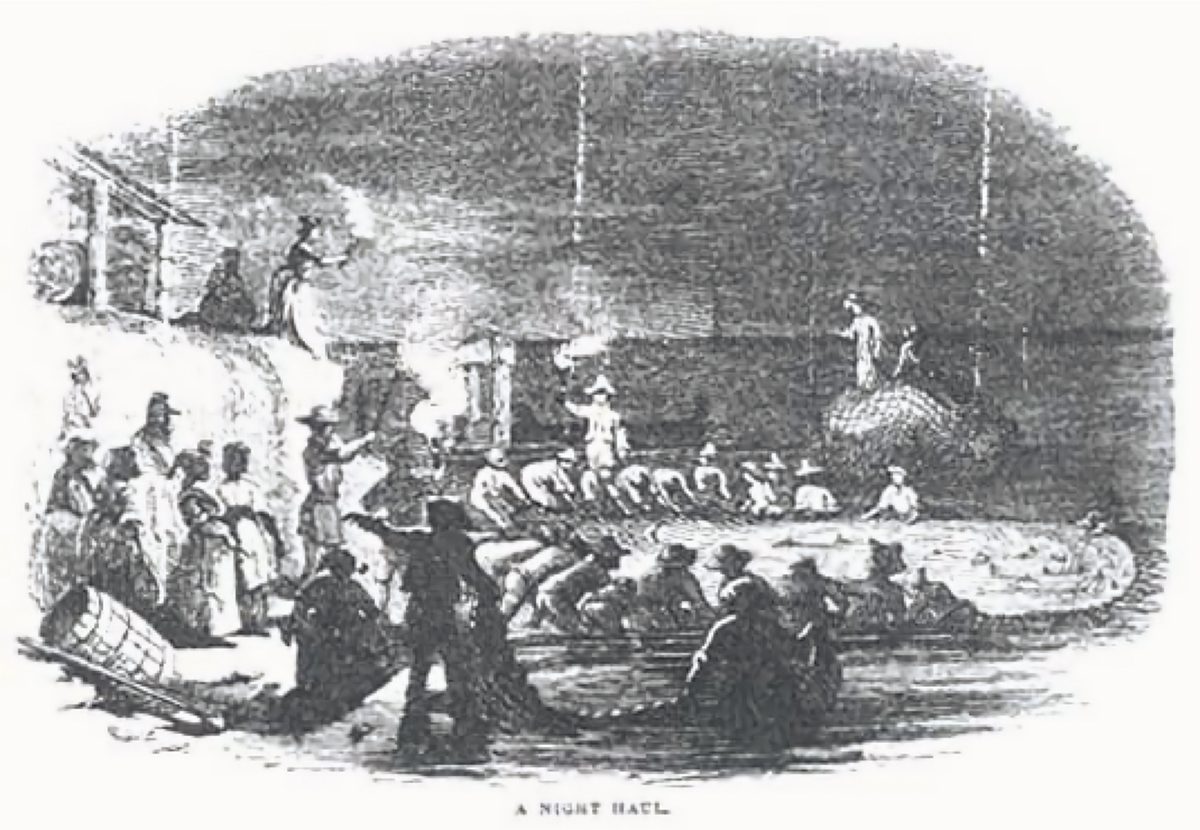

Using mostly seine nets, the amount of fish landed and processed here was sizable. In a 2002 report placing Bertie County plantation Elmwood on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), the study’s authors wrote, “The heyday of fishing in the Albemarle Sound and its tributaries was during the antebellum period … During the 1840s and 1850s it was not unusual for large soundside fisheries to experience a single seine haul containing in excess of 100,000 fish, all of which were cleaned and packed for shipping by the time the next seine haul was landed five or six hours later.”

Little had changed 45 or 50 years later, other than the use of steam winches to haul the net in, when The Semi-Weekly Fisherman & Farmer described the harvest in its October 21, 1887, edition.

Supporter Spotlight

“The large seines nets in the Albemarle Sound and Chowan River are from 2000 to 2400 yards long …They are laid out in the water and hauled in, about five times in every twenty-four hours, and sweep a square mile or more of water. It catches everything that it encircles. Steam is employed by most of them both in the laying of them out in the water, and on shore for hauling them in,” the newspaper reported.

The spawning run for the herring and shad was brief — perhaps 10 weeks — but the labor needs were extraordinary. In “A Cultural History of River Herring and Shad Fisheries in Eastern North Carolina,” a 1997 East Carolina University master’s thesis, Charles Heath describes the Fisherman’s Courts where workers were recruited.

“During the antebellum period, the Fisherman’s Court was established in several counties surrounding the Albemarle Sound. The court was held the third Monday in February and served as a clearing house for fisheries labor,” he wrote. “Fishery operators came to the court to hire slaves, as well as free whites and blacks. Potential laborers, free blacks and whites, were said to have come to the court from as far inland as fifty miles or more for the opportunity to work at the fisheries. In May, the court was held again and the fishery owners settled debts and paid the free laborers and the owners of the slaves for their work.”

It was brutal work. The hours, according to eyewitnesses, were around the clock.

Sally Moore Koestler has created a website, “Sally’s Family Place,” where she records “Tales of NC Roanoke-Chowan and elsewhere.” On her page recounting seine fishing, she has included a letter written to Lucy Daniels by her grandmother, Ella Harrell Evans. Koestler places the date of the letter around 1965 and in an email wrote that she believes it is possible to “… place the grandmother’s notes about 1900.”

The details in the letter paint an extraordinary picture of who the workers were and what the work was like.

“Years ago at Capehart’s fishery which was owned by Mr. William Capehart, he runned (sic) a public fishery and had forty-five or fifty negroes that helped him,” Evans writes.

She goes on to detail the working conditions, writing to her granddaughter, “The men would start to work about three o’clock in the morning and work in the rain, snow, ice and sleet and sometimes their clothes would be frozen. They wore oil suits, hats and long hip boots. The men would work until 12 o’clock every night and go back at three in the morning.”

Her recollection of the size of the catch confirms how large the haul was.

“The negroes would line up on each end of the seine and pull the seine in, it would take around five hours, depending on the amount of fish in the seine … They would have to stake it out because there would be so many fish in the seine, around two hundred fifty thousands. They would have to get it close end to dip part of the fish out so they could pull the seine in. Most days they could make four hauls a day with about about fifty or seventy five thousands,” Evans writes.

Other accounts note even larger harvests. The Elmwood National Register of Historic Places study authors describe what the fishing was like at its peak.

“Although the notably large hauls at Avoca (the south bank of Salmon Creek) comprised of approximately 300,000 river herring and 6,000 shad, such operations were recorded as having caught as many as 400,000- 500,000 river herring in a single haul of the seine. Observers noted that from 1878 to 1883 the total catch at one Chowan River fishery was over fifteen million river herring,” the study notes.

The Evans letter and other accounts written by eyewitnesses are richly detailed, but in his master’s candidacy prospectus, East Carolina University student Levi Holton notes all the eyewitness accounts of the Salmon Creek fishery are missing an important point of view.

“The initial gathering of primary source materials indicates that the record of experiences, points of view, and stories of African Americans have been written almost exclusively by white Americans. This is a limitation to the accurate interpretation of historical records concerning African Americans and what has been written may suffer from the constraints of bias and potential prejudice,” he writes.

Holton’s prospectus includes a reexamination of records, most of which have not been digitized. Additionally he is proposing deep mapping of Salmon Creek, a relatively new geographic information system-based archaeological tool that creates a 3-D historic overview of the research site.

River herring continued to be commercially harvested well into the 20th century, but today there are no nets strung across Salmon Creek catching the fish on their spawning run.

The massive harvests of the fish were likely a factor in the river stock’s decline, but it was not the only cause.

In a 2017 fishery management plan for river herring, North Carolina Marine Fisheries noted, “considerable habitat area has been lost through wetland drainage, stream channelization and conversion to other uses.” The plan continues that oxygen-consuming wastes are discharged into several streams, “causing nuisance algal blooms, fish kills, and fish diseases over the years.”