JARVISBURG — Lewis Wescott was a Black man who was born in North Carolina just before the Civil War and died just before World War II. Little has been known about his life except that he was a surfman, a Coast Guard captain and a hero who participated in one of the most daring ocean rescues in Outer Banks history.

But thanks to the serendipitous discovery of his gravesite by a retired Coast Guard commander, we now know that Wescott, a member of the famed all-Black crew at Pea Island Life-Saving Station, lived two weeks short of 83 years, and he is buried next to his wife in Jarvisburg, a community on the Currituck County mainland.

Supporter Spotlight

“I didn’t really need to do much research,” Gavin Wente, the property owner, recently told Coastal Review. “I spent almost 30 years in the Coast Guard, so I was familiar with the lifesaving service on the Outer Banks, specifically the story behind Pea Island … and I was familiar with some of the names like Etheridge and Wescott.”

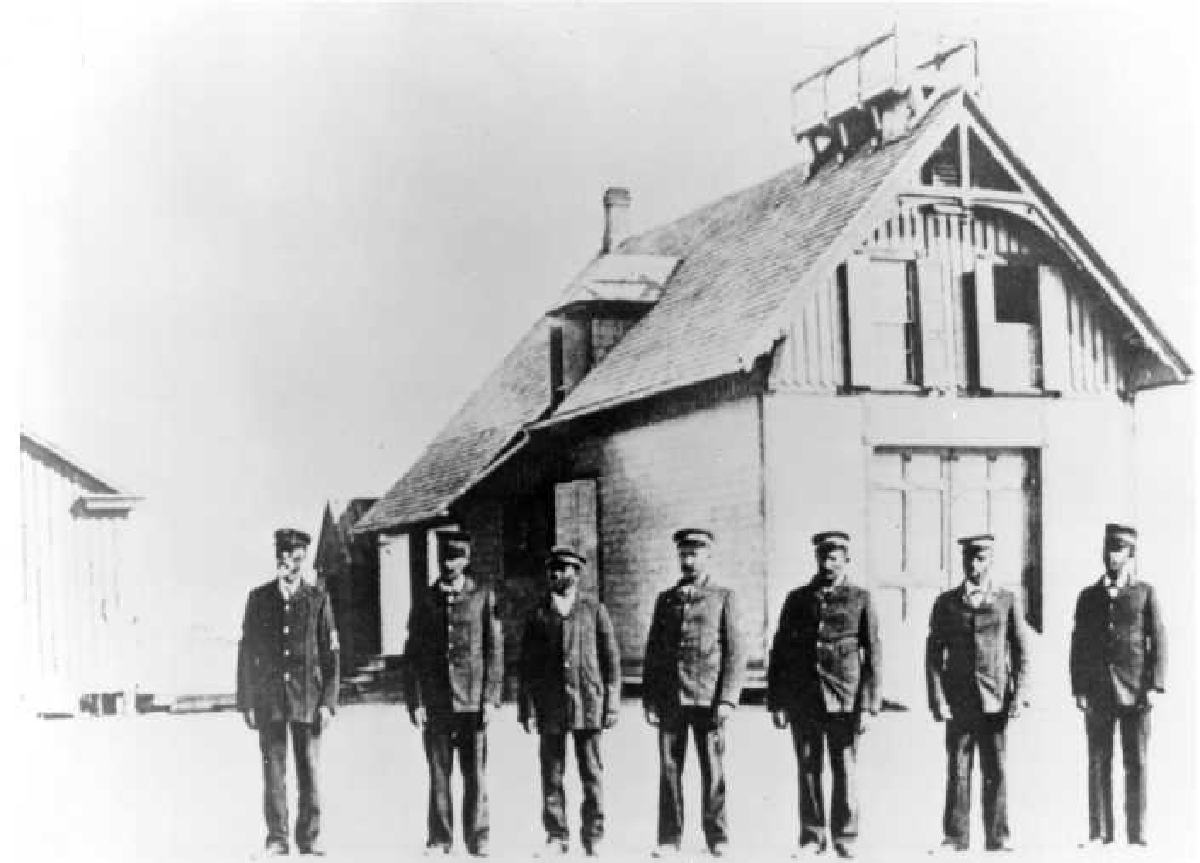

Richard Etheridge, the first Black appointed keeper in the U.S. Life-Saving Service, led his six all-Black crewmen — including Wescott — into a seething, stormy sea at night during an October 1896 hurricane to rescue terrified passengers and crew on the wrecked schooner E.S. Newman. With just a rope tying two surfmen together, the crew took turns plunging 10 times into the water, eventually rescuing every single person.

With the end of Reconstruction the next year, followed by decades of Jim Crow, the amazing feat — and the heroism of the Pea Island crew — soon faded from history.

When Wente and his wife Renee moved in April 2022 to their new home on 31 acres along the Currituck Sound, they were aware of two fenced-in cemeteries on the land. But it wasn’t until around Thanksgiving, when the overgrowth of poison ivy and Virginia creeper had died off, that the couple and their children and grandchildren were able to investigate.

“We’re out there starting to clean off some of the gravestones, and they started in the back corner where Wescott’s grave was,” Gavin Wente said. “And there must have been a foot of pine straw and overgrowth on top of that crypt.”

Supporter Spotlight

But before long, Wente recalled, his daughter announced that she had found a gravestone engraved with the words “Capt. L.S. Wescott.” After looking at the grave, he went online, checked the records, and was thrilled to confirm what he suspected.

“Yeah it was him,” Wente said. “So, we think that was one of the signs that this is where we were supposed to be.”

Not only did the couple find it significant that Wente knew who Wescott was, his grave was also the first one the family cleared.

“We don’t know why they went back to that righthand corner and started there,” said Renee Wente. “They said they just felt something under their feet and there it was.”

The Wentes said that the county shows no record of Wescott being buried on their property, and she is not aware of any record of his life in Currituck.

Wescott’s grave, a large crypt with engravings on top of it, is within the larger cemetery at the rear of the property, which appears to contain about 15 to 20 graves, Gavin Wente said. Near Wescott’s grave are two gravestones, one marked William Wescott and the other, Henry Wescott.

There are also small gravestones with initials, ending in “W.”

Another small cemetery with about 10 graves is at the front of the property.

After Wente, 61 and a former Coast Guard commander, discovered Wescott’s burial site, he contacted Coast Guard Atlantic area historian Bill Thiesen about finding the grave.

“I think it’s extremely significant,” Thiesen told Coastal Review. “I would have assumed that all of the final resting places for the Pea Island lifesavers would have been known, if not recognized. And then I learned that actually, Wescott’s was kind of lost and forgotten.”

In general, he said, Coast Guard personnel burial sites don’t get the attention that those in other military branches do, partly because it was not an official military organization until 1915, when it also absorbed the lifesaving service. Also, the lifesaving service had been regarded as more of a federal humanitarian service.

All other members of the Pea Island crew have some sort of marker or monument, except for William Irving, who may be interred in a family cemetery that has been forgotten, which was likely the case with Wescott.

Thiesen said that records prior to 1915 are slim, especially for Black individuals and other minorities. Even the “tremendous and remarkable achievement” of the Pea Island crew in the E.S. Newman rescue was not honored, or even noted by the Coast Guard for 100 years, when members were posthumously awarded the Gold Lifesaving metal in 1996.

Before the Civil War, some of the Black members of the U.S. Lifesaving Service were enslaved, but there were also free men who served, Thiesen said.

“The military agencies were officially desegregated by Truman in 1948, but the Coast Guard had already integrated African Americans into the service during World War II,” Thiesen said.

Even earlier, some Black men served under the same rating system as white men, including at Pea Island. “Not very frequently,” he added,” but far earlier than other military organizations.”

Starting in 1880, Richard Etheridge was the first African American to command a base of operations in the U.S., as keeper of the Pea Island Life-Saving Station on Hatteras Island. After Etheridge’s death, Wescott was appointed keeper in September 1900 and served until 1916.

Significantly, he was the officer in charge of Pea Island when the U.S. Life Saving Service merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the modern-day Coast Guard.

The Coast Guard also had Black officers in charge of cutters — Coast Guard vessels longer than 65 feet — one in 1928, Thiesen said, and there was also an all-Black cutter crew in 1920.

“And then the Coast Guard really was the trailblazer for desegregation, starting in 1942, when some Coast Guard cutters were used as kind of experiments for desegregation to see how it worked out before they introduced it to the Navy.”

Thiesen said that the Coast Guard plans to acknowledge the Wescott burial site with photographs and writings, but otherwise it is limited from doing anything more formal, especially on private property.

“The Coast Guard doesn’t have the funding to recognize all of the Coasties that have been interred over the years,” he said.

But the Wentes’ plan to try to get assistance in clearing and cleaning the cemeteries, and continue to investigate Wescott’s history, as well as the other graves.

“When we look at it, I just can’t help but think to myself ‘My word! This graveyard has been here when our nation was in its infancy,’” Renee Wente said. “It’s just remarkable.”

Wente added that the family feels so honored to have the burial site on their property and wants to make sure that the Pea Island hero gets the recognition he deserves.

Although the nonprofit Pea Island Preservation Society has not been directly involved in anything to do with the Wescott burial site, the group is pleased about the increased attention on the Pea Island story.

“I think this discovery is a great reminder to do the research of this ‘uncovered history,’” said Joan Collins, the group’s director of outreach and education. “Because this history hasn’t been told.”

Gavin Wente still can’t get over that such a historically important Coast Guardsman has his resting place on his land.

“It’s sad that Capt. Wescott’s legacy was lost from years of neglect in this grave yard,” Gavin Wente wrote on a Facebook post. “It will be this old, retired Coast Guardsman’s privilege to ensure this is corrected and I will maintain this grave yard as long as I’m able.”