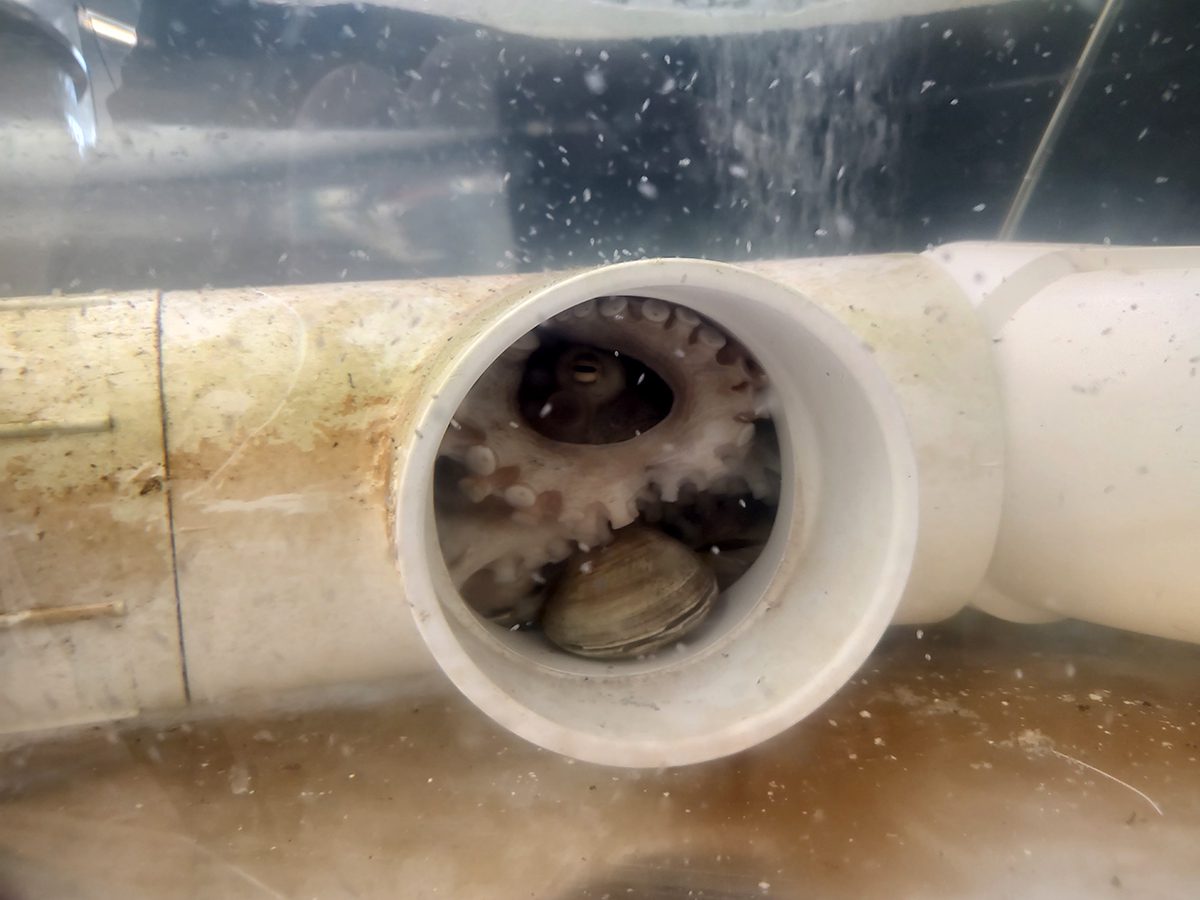

MOREHEAD CITY — Tucked away on the floor near a couple pieces of equipment in the busy aquaculture lab at Carteret Community College is an unassuming round, nearly waist-high, clear tank with a few sections of hard, white plastic pipes roughly the diameter of salad plates placed on the bottom.

Inside one section of T-shaped pipe, a female common octopus, Octopus vulgaris, has been incubating her eggs. Over the last week, her hundreds of thousands of eggs have been hatching, filling the tank with tiny gray wiggly specks, the paralarvae or newly hatched octopuses.

Supporter Spotlight

Aquaculture Operations Manager Bryan Snyder explained Wednesday morning that the female octopus had been hiding in the pipe with her remaining eggs. Aquaculture is the farming and husbandry of aquatic organisms.

“She probably still has a few unhatched eggs in there. They don’t hatch at exactly the same time,” Snyder said, adding that the mother’s job while the eggs are incubating and hatching is to protect her eggs and keep water moving over the eggs.

Snyder was in the middle of teaching students in his hatchery management II class how to spawn clams. They were standing around a spawning table, a long, narrow tank that can hold about 6 inches of water. The students had carefully placed rows of clams in the water, which was set at a temperature to simulate winter conditions in the wild. Snyder was explaining how to properly increase the temperature to encourage reproduction.

The class focuses on facility needs, hatchery production planning and propagation techniques for species, including clams, shrimp, catfish, hybrid striped bass and rainbow trout. It’s the next step for students after taking the basics of fish and shellfish propagation taught in hatchery management I.

The classes are part of the college’s Aquaculture Technology program that focuses on saltwater species like oysters, clams, softshell crabs, and marine finfish like flounder, drum and bait minnows, according to the website. Program graduates have the option to continue their education at the college, transfer classes to a four-year university, start their own fish or shellfish farm, or work as a technician at any aquaculture operation.

Supporter Spotlight

Aquaculture Department Chair David Cerino told Coastal Review Thursday that the program has had several octopuses lay eggs over the years, but they didn’t have all the live feeds needed for successful rearing. “We are hoping to have a better chance this time applying what we have learned in previous attempts,” he said.

Cerino said they collected the female octopus along with a male Nov. 4 at Radio Island.

“We put both in the tank together and they immediately mated,” he explained. “We then released the male that same day to avoid aggression between the two.”

Snyder said while looking at her tank Wednesday that the octopus she was older and had probably already mated before. “They can hold onto the sperm package from the male for quite a while before they fertilize their eggs, but we actually watched this one mate. We took the male out because they are cannibalistic, they’ll eat each other.”

The female stored sperm until about Jan. 18 when she laid the eggs. The eggs incubated for 21 days before they began hatching and have continued for about a week with peak hatch on days two and three, Cerino said.

Typically, a common octopus will lay between 100,000 and 500,000 eggs at a time. After the eggs hatch, the mother octopus usually dies.

“That’s the normal lifecycle,” Snyder said. “They’re not very long-lived animals, they normally live a year or two, and then once they reproduce that’s the end of their natural life cycle, generally.”

Snyder continued that having a pregnant octopus while a hatchery class is taking place is “a good trial for not only our students but us as well” because larvae are difficult to raise, and most people are not successful.

Snyder said they’ll release some of the paralarvae back into the wild and they’ll also try and raise the octopuses.

Snyder said that they’ve built a larval system in the lab to raise the paralarvae. This system has four tanks that can house up to 6,000 paralarvae per tank. Snyder said they move the paralarvae by scooping them up with a lab-grade pitcher, then the pitcher is floated inside the tank so the water temperature in the pitcher will acclimate to that of the water of the tank and then they’ll gently release the paralarvae into the tank.

“We don’t know how successful we’ll be once they turn into hatchlings — to juvenile octopus,” he said, adding that’s when they turn cannibalistic. “We have to add a lot of hiding spots to the tanks so they don’t eat each other.”

Cerino said that the tanks are 100-gallon black tanks with moderate aeration.

“We add brine shrimp nauplii and two species of copepods daily as food for the paralarvae and add three species of microalgae to nutritionally enrich the feeds and add color to the water, reducing light penetration and improving visual contrast of the prey for feeding,” Cerino said. “We periodically exchange the water in the tanks to maintain water quality. Published reports of rearing attempts suggest that successful rearing for the first 30 days is readily achieved, but survival to juvenile octopus at about 45-50 days is very low.” Nauplii is plural for nauplius, the is the first larval stage for many crustaceans. Copepods are small crustaceans.

As of Thursday, “we have very high survival and the paralarvae are feeding well,” Cerino said.

In the lab beside the female octopus’ tank, it’s hard not to notice the row of tanks housing pairs of clownfish, another species the class is learning to breed.

The way the tank is set up, a shelf placed inside acts as a reef rock, where the clownfish will stick the eggs, “but sometimes if their water quality isn’t just right or they get stressed out, they’ll actually eat their eggs and try again,” Snyder said Wednesday.

The bigger fish in the tank is the female and the next biggest is the male that she breeds with and there’s a bunch of other males that just kind of hang out, Snyder explained. When the female dies, the biggest male will turn into a female and then the next biggest male will move up the ranks.

Snyder said they’re trying to grow corals, too, and have a touch tank onsite filled with animals collected from Bogue Sound, which is just behind the aquaculture building.

The touch tank has whelks, clams, vegetarian snails and other marine life, he said. The tank is a way to teach students how to care for a bunch of different animals and learn which can live together.