A Topsail Island board hopes to prompt change to a North Carolina law that requires beach towns to foot the costs of building and maintaining hardened beach erosion-control structures.

When the North Carolina General Assembly in 2011 repealed a 30-year-old ban on the structures, known as terminal groins, legislators determined that state funds cannot be spent “for any activities related to a terminal groin and its accompanying beach project … unless the General Assembly enacts legislation appropriating funds explicitly for such purpose.”

Supporter Spotlight

The Topsail Island Shoreline Protection Commission, or TISPC, has included in its goals for 2023 advocating for a change to state funding and local financing guidelines for terminal groins, a move that could benefit North Topsail Beach.

North Topsail is currently in a long-haul process to determine whether a terminal groin is the town’s best option in curbing erosion at New River Inlet.

TISPC Chairman and Topsail Beach Mayor Steve Smith said the commission’s move is part of a process that “would like to see if the possibility exists of the state reconsidering their position on funding.”

The commission, made up of elected officials and local government appointees from the island’s three beach towns and Onslow and Pender counties, functions as a collaboration to preserve the 26-mile-long barrier island’s beaches and surrounding waterways.

While each town has its own set of needs, the differences are perhaps most stark at each end of the island.

Supporter Spotlight

In Topsail Beach, the southern tip of the island has been accreting, building up an expanse of unspoiled, undeveloped land.

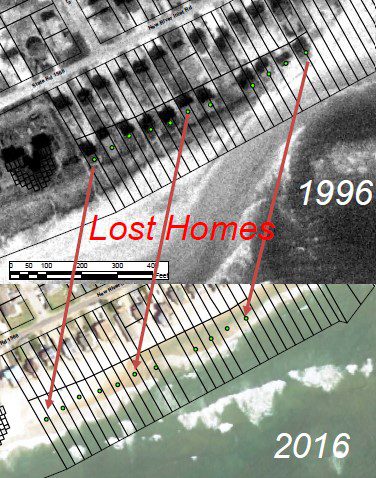

The scene at the island’s northernmost end is the complete opposite, where the battle against erosion is as constant as the ebb and flow of waves on North Topsail’s ocean shore.

Initial attempts to curb erosion at the north end began around the early 2000s.

In early 2013, the town had high hopes its decision to proceed with a project to realign the New River Inlet channel would adequately reduce erosion at the north end.

It did not.

By then, the state’s longstanding ban on hardened beach erosion-control structures had been repealed, leaving the town the possible option to build a terminal groin.

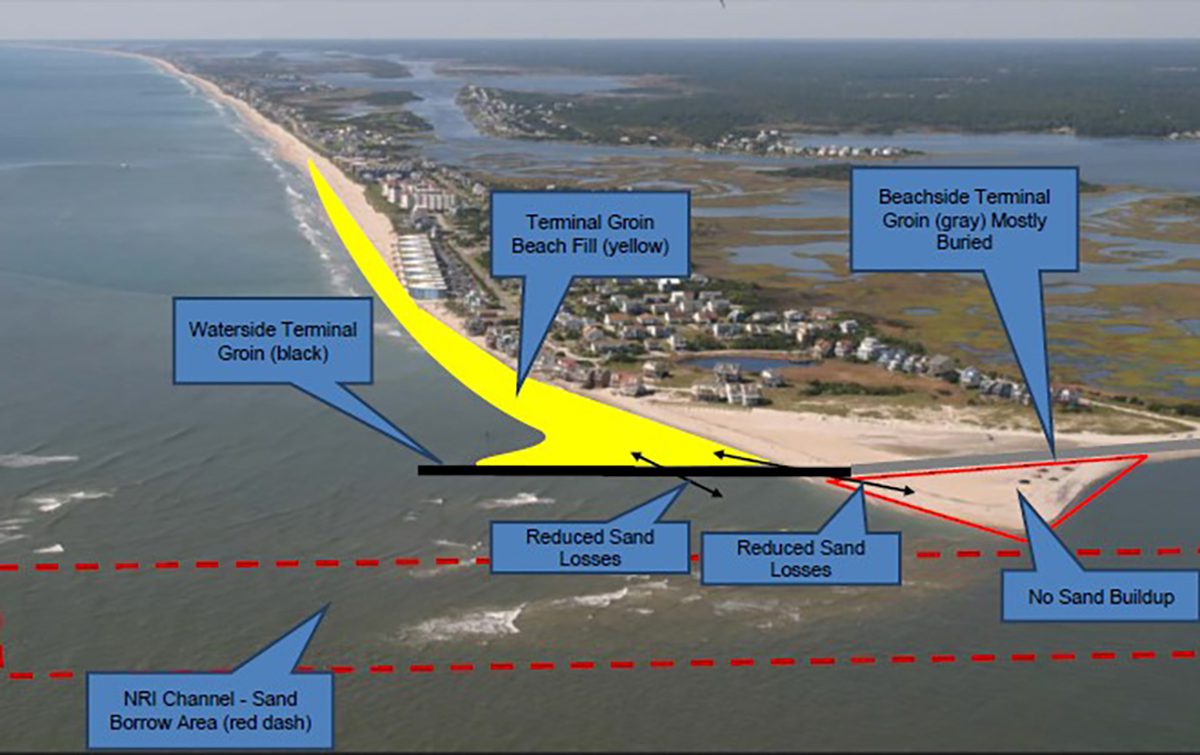

A terminal groin is a wall-like structure made of rock or other material placed perpendicular to the shore and adjacent to an inlet, at the island’s terminus, to control erosion.

Two North Carolina Beach towns – Bald Head Island, and more recently, Ocean Isle Beach – have built terminal groins since 2011.

The General Assembly’s decision more than a decade ago to repeal the ban on terminal groins was met with opposition from some prominent coastal scientists in the state and environmental groups, including the North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review.

They argue hardened beach erosion structures increase erosion farther down beach and are expensive to build and maintain.

Roughly a year after the New River Inlet channel-realignment project was completed, North Topsail Beach received an emergency permit to build a sandbag revetment at the northern end to protect homes and condominiums.

In all, about 3,600 feet of sandbags have been placed along the ocean shore from the inlet south to Topsail Reef condominiums.

“We are getting close to when we need to renew our permit,” said North Topsail Beach Mayor Pro Tem Mike Benson.

Benson, who is a sitting board member of the TISPC, emphasized that the town had not decided whether to build a terminal groin. In fact, no past boards of aldermen had voted to construct a terminal groin.

Coastal engineering firm Applied Technology & Management Inc., in 2018 presented to the town a recommendation to build a terminal groin spanning a minimum of 1,500 feet.

The next year, the Army Corps of Engineers signed off on a third-party agreement with North Topsail Beach authorizing an environmental engineering firm to serve as an independent contractor to evaluate all alternatives, including a terminal groin, at the inlet.

“We’re in the very beginning stages because (Hurricane) Florence came along and COVID came along,” Benson said. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “is really just getting into this for us and they haven’t published a notice of intent yet.”

The initial estimated cost presented to the town to build a terminal groin was around $10 million, he said.

“We have no idea what the cost would be today,” Benson said. “We’re looking out to the future to see how we can get some state help.”

Legislators whose districts include North Topsail Beach did not respond to requests for comment.

North Topsail Beach elected officials in recent years have worked to prioritize spending to ensure the town pays off debt while funding capital projects and beach nourishment projects.

In 2021, elected officials there backed away from a proposed joint project with Surf City and the Corps that would have secured routine beach nourishment along the southernmost 4.5 miles of North Topsail’s ocean shoreline for 50 years.

The board said the town could not fund its more than $33 million of the project’s cost.